Elijahn Restoration: Difference between revisions

Continuator (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (14 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Natopian article}}{{Normark article}}{{SANE article}}{{Bovinism article | {{Natopian article}}{{Normark article}}{{SANE article}}{{Bovinism article}} | ||

{{Infobox military conflict | {{Infobox military conflict | ||

| conflict = Elijahn Restoration<br><small>''aka [[Operation Sacred Ground]]''</small> | | conflict = Elijahn Restoration<br><small>''aka [[Operation Sacred Ground]]''</small> | ||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

* [[Arsenios Kallistos]]<br><small>([[Metrobosarch of Keltia]])</small> | * [[Arsenios Kallistos]]<br><small>([[Metrobosarch of Keltia]])</small> | ||

{{team flag|Constancia}} | {{team flag|Constancia}} | ||

* | * Brigadier Erasmus Korvel<br><small>(6th "Nord" Brigade)</small> | ||

| commander2 = ''Various''<br><small>(fragmented command)</small> | | commander2 = ''Various''<br><small>(fragmented command)</small> | ||

| units1 = {{team flag|Raspur Pact|flag}} [[Keltia Command]] | | units1 = {{team flag|Raspur Pact|flag}} [[Keltia Command]] | ||

| Line 45: | Line 44: | ||

* {{team flag|Natopia|flag}} [[Ayreon Tomb Guard]] | * {{team flag|Natopia|flag}} [[Ayreon Tomb Guard]] | ||

| units2 = Confederacy militias<br><small>(fragmented, no unified command)</small> | | units2 = Confederacy militias<br><small>(fragmented, no unified command)</small> | ||

| strength1 = ''Estimated division-level strength''<br>Constancian brigade<br>ESB logistics support | | strength1 = ''Estimated division-level strength''<br>~21,600 personnel<br>Constancian brigade<br>ESB logistics support | ||

| strength2 = ''Estimated | | strength2 = ''Estimated 3,300 fighters''<br><small>(varying quality; Konungsheim and Nordiskehjem areas)</small> | ||

| casualties1 = | | casualties1 = 0 killed<br>13 wounded<br>2 [[Dingo-class shuttle]]s lost | ||

| casualties2 = | | casualties2 = ~85 killed (est.)<br>Unknown wounded<br>~400 captured/disarmed | ||

| notes = Military operations coordinated with civilian "[[Elijahn Restoration#The Stampede to Konungsheim|Stampede to Konungsheim]]" settlement initiative | | notes = Military operations coordinated with civilian "[[Elijahn Restoration#The Stampede to Konungsheim|Stampede to Konungsheim]]" settlement initiative | ||

| campaignbox = | | campaignbox = | ||

}} | }} | ||

The '''Elijahn Restoration''', also known by its military | The '''Elijahn Restoration''', also known by its military designation ''[[Operation Sacred Ground]]'', is a territorial claim and settlement initiative launched by the [[Bovic Empire of the Natopian Nation]] in 20.IV.{{AN|1752}} to reclaim portions of the former [[Kingdom of Normark]] abandoned during the [[East Keltian Collapse]] of {{AN|1737}}. The claim encompasses eight former Norse bailiwicks, collectively termed [[Elieland]], along the southwestern coast. These include the former capital of [[Konungsheim]] (known in Natopian tradition as [[Elijah's Rest]]) and the port settlement of [[Nordiskehjem]], with a combined pre-collapse population of approximately 4.1 million. | ||

The initiative | The initiative draws from religious obligation, strategic opportunity, and domestic political need. The [[Dozan Bovic Church]] endorsed the restoration on theological grounds, arguing that 139 years of proximity to the remains of [[Elijah Ayreon|Saint Elijah Ayreon]] consecrated the ground of Konungsheim itself, and that the [[Prophecy of Athlon]] demands the faithful prepare for the [[Butter Bull]]'s return. Strategically, the claim expands [[Raspur Pact]] presence in northern [[Keltia]] and complements [[Nouvelle Alexandrie]]'s [[Arctic Base Thorgils]] on nearby [[Los Bananos]]. Politically, the [[Marco Lungo III|Lungo III]] government sought to demonstrate renewed national purpose following the controversies of the [[Emmanuel Aristarchus|Aristarchus]] years. | ||

Military operations commenced in VIII.{{AN|1752}}, with [[Konungsheim]] and [[Nordiskehjem]] secured within two weeks. [[Pentheros]] [[Sergius Hergones]] announced that Father [[Arsenios Kallistos]], a priest of the [[Phallic Cult]], would serve as the new [[Metrobosarch of Keltia]], the first holder of that office to actually reside in Keltia since the collapse. As of 12.X.{{AN|1752}}, the military phase has concluded, but the civilian reconstruction effort faces severe challenges. The region's polar climate, its extreme remoteness from Natopian supply centers, and fifteen years of infrastructure decay combine to make the restoration's long-term viability uncertain. | |||

==Background== | ==Background== | ||

[[Natopia]]'s connection to the [[Normark]] region predates the Kingdom of Normark itself. In {{AN|1615}}, the demigod [[Athlon]] took charge of the abandoned city of [[Konungsheim]] and renamed it [[Elijah's Rest]], initiating Natopian settlement in northern [[Keltia]]. The region grew under Natopian administration | [[Natopia]]'s connection to the [[Normark]] region predates the Kingdom of Normark itself. In {{AN|1615}}, the demigod [[Athlon]] took charge of the abandoned city of [[Konungsheim]] and renamed it [[Elijah's Rest]], initiating Natopian settlement in northern [[Keltia]]. The region grew under Natopian administration. In {{AN|1649}} it was formalized with the establishment of the [[Elian Union]] as a super-[[Demesne|demesne]] encompassing [[Elijah's Rest]], [[Normark]], the [[Leng|Kingdom of Leng]], the [[Two Martyrs|Viceroyalty of The Two Martyrs]], and the [[Saint Christopher's|Duchy of New Aquitane]]. | ||

Normark was established as a distinct Natopian demesne in {{AN|1657}}. The territory remained under Natopian sovereignty until {{AN|1678}}, when a referendum approved transfer to [[Elwynn]]. Normark subsequently passed through Elwynnese administration, survived the [[Second Elwynnese Civil War]], and achieved independence in {{AN|1703}} under King [[Tarjei Thorgilsson]]. Throughout these transitions, the Natopian cultural and religious imprint remained significant, particularly in the veneration of Saint Elijah Ayreon. | Normark was established as a distinct Natopian demesne in {{AN|1657}}. The territory remained under Natopian sovereignty until {{AN|1678}}, when a referendum approved transfer to [[Elwynn]]. Normark subsequently passed through Elwynnese administration, survived the [[Second Elwynnese Civil War]], and achieved independence in {{AN|1703}} under King [[Tarjei Thorgilsson]]. Throughout these transitions, the Natopian cultural and religious imprint remained significant, particularly in the veneration of Saint Elijah Ayreon. | ||

| Line 76: | Line 73: | ||

The [[Phallic Cult]], a mystery religion established in {{AN|1573}} by Pentheros [[Nathan Waffel-Paine]] (as Theodores Athanatos), maintains a distinctive relationship with Saint Elijah's memory. Elijah appears in the Phallic pantheon alongside [[Bruno of Macon|Bruno]], [[Priapus]], and the [[Winged Phallus]], honored as patron of romantic love. The [[Apotheosis of Elijah]], describing Nathan's deification of his martyred husband, constitutes the sole [[Tetrabiblios|Tetrabiblical]] reference to the Phallic mysteries. | The [[Phallic Cult]], a mystery religion established in {{AN|1573}} by Pentheros [[Nathan Waffel-Paine]] (as Theodores Athanatos), maintains a distinctive relationship with Saint Elijah's memory. Elijah appears in the Phallic pantheon alongside [[Bruno of Macon|Bruno]], [[Priapus]], and the [[Winged Phallus]], honored as patron of romantic love. The [[Apotheosis of Elijah]], describing Nathan's deification of his martyred husband, constitutes the sole [[Tetrabiblios|Tetrabiblical]] reference to the Phallic mysteries. | ||

The Cult's emphasis on masculine virtues, assertive action, and sacred aspects of virility | The Cult's emphasis on masculine virtues, assertive action, and sacred aspects of virility proved significant in the theological arguments advanced for the restoration. | ||

===East Keltian Collapse (1737)=== | ===East Keltian Collapse (1737)=== | ||

| Line 90: | Line 87: | ||

===Arctic Base Thorgils and the Boreal Air Bridge=== | ===Arctic Base Thorgils and the Boreal Air Bridge=== | ||

{{Main|Boreal Air Bridge|Arctic Base Thorgils}} | {{Main|Boreal Air Bridge|Arctic Base Thorgils}} | ||

The [[Boreal Air Bridge]], a strategic air corridor connecting [[Nouvelle Alexandrie]] to the [[Benacian Union]] via northern [[Keltia]], had relied on [[Normark]]'s infrastructure prior to {{AN|1737}. The collapse terminated the main route, severely impacting the [[Benacian Union]]'s ability to withstand the ongoing Shirerithian maritime blockade during the [[Shiro-Benacian War]]. | The [[Boreal Air Bridge]], a strategic air corridor connecting [[Nouvelle Alexandrie]] to the [[Benacian Union]] via northern [[Keltia]], had relied on [[Normark]]'s infrastructure prior to {{AN|1737}}. The collapse terminated the main route, severely impacting the [[Benacian Union]]'s ability to withstand the ongoing Shirerithian maritime blockade during the [[Shiro-Benacian War]]. | ||

In response, [[Nouvelle Alexandrie]] conducted [[Operation Polar Crown]] (VI–VIII.{{AN|1738}}), establishing [[Arctic Base Thorgils]] on [[Los Bananos]], an island formerly administered by [[Normark]]. The operation created a permanent military installation featuring a 3,000-meter all-weather runway, advanced radar systems, and air defense capabilities. AB Thorgils restored a northern air corridor, allowing transport aircraft to circumvent the [[Shireroth|Shirerithian]] blockade. | In response, [[Nouvelle Alexandrie]] conducted [[Operation Polar Crown]] (VI–VIII.{{AN|1738}}), establishing [[Arctic Base Thorgils]] on [[Los Bananos]], an island formerly administered by [[Normark]]. The operation created a permanent military installation featuring a 3,000-meter all-weather runway, advanced radar systems, and air defense capabilities. AB Thorgils restored a northern air corridor, allowing transport aircraft to circumvent the [[Shireroth|Shirerithian]] blockade. | ||

AB Thorgils has operated successfully as an isolated island installation | AB Thorgils has operated successfully as an isolated island installation. [[Raspur Pact]] planners recognize that additional mainland presence could enhance operational flexibility and overall regional capacity, though skeptics note that the logistics of sustaining such a presence would be formidable. | ||

===Fifteen years in the Green (1737–1752)=== | ===Fifteen years in the Green (1737–1752)=== | ||

For fifteen years following the collapse, the former territory of [[Normark]] | For fifteen years following the collapse, the former territory of [[Normark]] remained in the Green, outside organized state control. The [[Confederacy of the Dispossessed]] expanded its presence across portions of the abandoned territory, though the extent of their actual control varied considerably by region. Some areas fell under direct Confederacy administration. Others experienced only periodic raiding. Still others were simply abandoned, their populations fled or dead. | ||

The southwestern coastal bailiwicks, adjacent to New Alexandrian-held [[Los Bananos]] and accessible by sea, | The southwestern coastal bailiwicks, adjacent to New Alexandrian-held [[Los Bananos]] and accessible by sea, experienced diverse fates. Intelligence regarding conditions on the ground remained fragmentary. Estimates of remaining population ranged widely. The status of infrastructure, including the sacred sites of Konungsheim, was unknown. Occasional reports from traders and refugees painted contradictory pictures of abandoned cities, remnant communities clinging to survival, opportunistic warlords, and environmental degradation. | ||

The outbreak of [[Northern Keltia respiratory syndrome]] in {{AN|1738}} contributed to [[Normark]]'s collapse and continues to pose health risks throughout the region. Industrial and military sites abandoned during the evacuation present unknown hazards. | The outbreak of [[Northern Keltia respiratory syndrome]] in {{AN|1738}} had contributed to [[Normark]]'s collapse and continues to pose health risks throughout the region. Industrial and military sites abandoned during the evacuation present unknown hazards. | ||

===The Lower Jangsong Campaign (1751–1752)=== | ===The Lower Jangsong Campaign (1751–1752)=== | ||

| Line 153: | Line 150: | ||

The [[Natopian Withdrawal from Whales]] ({{AN|1743}}–{{AN|1744}}), formalized in the [[Treaty of Sankt Rosa]], ended centuries of Natopian presence in southern [[Cibola]]. The withdrawal was presented as ''"decolonization"'' and relief from an ''"expensive colonial burden,"'' but images of hasty departure damaged Natopian prestige. "Who lost Whales?" became a recurring question in political discourse. | The [[Natopian Withdrawal from Whales]] ({{AN|1743}}–{{AN|1744}}), formalized in the [[Treaty of Sankt Rosa]], ended centuries of Natopian presence in southern [[Cibola]]. The withdrawal was presented as ''"decolonization"'' and relief from an ''"expensive colonial burden,"'' but images of hasty departure damaged Natopian prestige. "Who lost Whales?" became a recurring question in political discourse. | ||

The [[Universal Compact]] ({{AN|1744}}) resolved a constitutional ambiguity dating to [[Nathan Waffel-Paine]]'s era regarding [[Universalis]]'s autonomous status and territorial extent. Aristarchus personally intervened to include [[Sororiya]] within [[Universalis]]'s jurisdiction, citing [[Nathan Waffel-Paine|Nathan]]'s original oral promise. The ratification process proved brutal | The [[Universal Compact]] ({{AN|1744}}) resolved a constitutional ambiguity dating to [[Nathan Waffel-Paine|Nathan]]'s era regarding [[Universalis]]'s autonomous status and territorial extent. Aristarchus personally intervened to include [[Sororiya]] within [[Universalis]]'s jurisdiction, citing [[Nathan Waffel-Paine|Nathan]]'s original oral promise. The ratification process proved brutal. Aristarchus conducted aggressive whipping operations within his own [[Free Juice and Bagels Party|FJBP]] caucus, threatening committee assignments and deploying his considerable talent for cutting remarks against dissenters. The Compact passed along party lines, but internal wounds contributed to FJBP losses in the [[1744 Natopian Frenzy elections]]. | ||

Most damagingly, Aristarchus's reluctance to commit Natopian forces during the early phases of the [[Fourth Euran War]] drew criticism from [[Raspur Pact]] allies and domestic hawks alike. [[Vadoma I|Empress Vadoma I]] herself was in open conflict with the elected government over foreign policy. By the time the [[1745 Natopian Frenzy elections|1745 elections]] swept the [[Union Democratic Movement|UDM]] into power in coalition with the [[Nationalist and Humanist Party|N&H]], Aristarchus's legacy had become synonymous with retreat and isolation. | Most damagingly, Aristarchus's reluctance to commit Natopian forces during the early phases of the [[Fourth Euran War]] drew criticism from [[Raspur Pact]] allies and domestic hawks alike. [[Vadoma I|Empress Vadoma I]] herself was in open conflict with the elected government over foreign policy. By the time the [[1745 Natopian Frenzy elections|1745 elections]] swept the [[Union Democratic Movement|UDM]] into power in coalition with the [[Nationalist and Humanist Party|N&H]], Aristarchus's legacy had become synonymous with retreat and isolation. | ||

| Line 165: | Line 162: | ||

Yet Lungo faced a strategic landscape offering few easy options. The [[Fourth Euran War]] continued. Relations within the Raspur Pact remained complex. Major military adventures carried significant risks. The administration needed to demonstrate renewed national purpose without overextending Natopian capabilities. | Yet Lungo faced a strategic landscape offering few easy options. The [[Fourth Euran War]] continued. Relations within the Raspur Pact remained complex. Major military adventures carried significant risks. The administration needed to demonstrate renewed national purpose without overextending Natopian capabilities. | ||

The Elijahn Restoration offered something different: a religious cause that could unify the faithful across party lines, a strategic enhancement that complemented allied interests, and a symbolic reversal of the retreat narrative, all without directly challenging any major power or expanding the Fourth Euran War's scope. | The Elijahn Restoration offered something different: a religious cause that could unify the faithful across party lines, a strategic enhancement that complemented allied interests, and a symbolic reversal of the retreat narrative, all without directly challenging any major power or expanding the Fourth Euran War's scope. Whether Natopia could actually sustain such an enterprise in the polar wastes of northern Keltia remained to be seen. | ||

===The ailing Empress=== | ===The ailing Empress=== | ||

| Line 212: | Line 209: | ||

===Territory claimed=== | ===Territory claimed=== | ||

The Elijahn Restoration encompasses eight former bailiwicks of the [[Kingdom of Normark]], collectively designated as [[Elieland]] for administrative purposes. The claimed territory occupies the southwestern coastal region of former Normark, bounded by the [[Gulf of Jangsong]] to the north, [[the Green]] to the east, and open ocean to the south and west. | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

|- | |||

! Bailiwick !! Pre-collapse population (1721) !! Principal settlement !! Notes | |||

|- | |||

| Konungsheim || 1,850,000 || [[Konungsheim]] ([[Elijah's Rest]]) || Former capital; seat of [[Metrobosarch of Keltia]] | |||

|- | |||

| Nordiskehjem || 680,000 || [[Nordiskehjem]] || Primary deep-water port | |||

|- | |||

| Johansstrand || 420,000 || Johansstrand || Coastal fishing and maritime industries | |||

|- | |||

| Eriksfjord || 340,000 || Eriksborg || Agricultural hinterland | |||

|- | |||

| Sigurdheim || 290,000 || Sigurdheim || Mining and forestry | |||

|- | |||

| Thorvaldsby || 210,000 || Thorvaldsby || Transportation hub | |||

|- | |||

| Haraldvik || 180,000 || Haraldvik || Coastal settlement | |||

|- | |||

| Leifsdal || 130,000 || Leifsdal || Mountain communities | |||

|- | |||

| '''Total''' || '''~4.1 million''' || || 1721 census; current population unknown | |||

|} | |||

The claimed territory represents approximately one-third of Normark's 1721 population of 12,471,328. Actual population in {{AN|1752}} remains unknown. Mass evacuations in {{AN|1737}}, subsequent emigration, mortality from disease and disorder, and fifteen years of uncertain conditions have certainly reduced the number. Estimates range from several hundred thousand to possibly over two million, though the lower figures are considered more likely given the region's brutal climate and the collapse of organized society. | |||

===Geographic character and climate=== | |||

The claimed bailiwicks occupy the southwestern coastal region of former Normark. The ports at Nordiskehjem and Johansstrand provide maritime connections to [[Raspur Pact]] shipping lanes and the [[Boreal Air Bridge]] network. The claim area's position directly south of [[Nouvelle Alexandrie|New Alexandrian]]-held [[Los Bananos]] facilitates coordination with [[Arctic Base Thorgils]]. | |||

The region experiences harsh arctic and subarctic conditions. Winter temperatures frequently drop below -30°C and can reach -50°C in the interior during the coldest months. The summer growing season is limited to approximately four months, during which average temperatures hover between 5°C and 15°C. Pack ice affects northern coastal waters from late autumn through early spring, restricting maritime access during the coldest months. These conditions impose significant constraints on military operations, construction timelines, and agricultural development. The polar environment also provides natural defensive advantages against potential adversaries lacking arctic warfare capabilities, though it imposes equal hardship on the defenders. | |||

Pre-collapse Normark possessed substantial infrastructure in the claimed bailiwicks, including the international airport at Konungsheim, the deep-water port facilities at Nordiskehjem, a network of paved roads connecting major settlements, and a railway line linking Konungsheim to the interior. The condition of this infrastructure after fifteen years of abandonment and Confederacy occupation was unknown prior to operations but expected to have deteriorated significantly. Industrial sites, power generation facilities, and telecommunications infrastructure were similarly expected to require substantial rehabilitation or replacement. | |||

The claim excludes the eastern bailiwicks, including Revby, Dragevik, and regions bordering Mercury, as well as the southern interior where Confederacy presence was believed more substantial. The claimed region is geographically distinct from the eastern and central portions of former Normark annexed by [[Bassaridia Vaeringheim]] following the [[Lower Jangsong Campaign]], though the two territories share a land border. | |||

===Strategic considerations=== | ===Strategic considerations=== | ||

The claimed territory offers several strategic advantages for the [[Raspur Pact]]. Most significantly, it restores a mainland presence in northern Keltia after fifteen years of absence, providing depth to the isolated position of [[Arctic Base Thorgils]] on [[Los Bananos]]. Mainland facilities could enhance overall regional capacity through additional airfields, fuel storage depots, radar installations, and logistics infrastructure, reducing dependence on the single runway at AB Thorgils for all operations in the theater. | |||

The coastal position of the claimed bailiwicks allows resupply by both sea and air, providing redundancy in supply routes that the interior territories of former Normark would lack. The mountainous terrain of the Leifsdal and Sigurdheim bailiwicks provides natural defensive advantages against ground attack from [[the Green]], channeling potential Confederacy incursions through predictable avenues of approach. | |||

The claim also establishes a buffer preventing potential [[Confederacy of the Dispossessed]] consolidation adjacent to Los Bananos. While the Confederacy lacks the capability to threaten AB Thorgils directly, a Confederacy-controlled mainland opposite the island could complicate air and sea operations in the region. | |||

===Coordination with Nouvelle Alexandrie=== | ===Coordination with Nouvelle Alexandrie=== | ||

Chancellor [[Marco Lungo III|Lungo III]] consulted with [[Nouvelle Alexandrie]] prior to the public announcement. The Natopian claim complemented rather than competed with the New Alexandrian position on [[Los Bananos]]. [[Arctic Base Thorgils]] had operated successfully as an isolated island installation since {{AN|1738}}; Natopian mainland presence would create opportunities for enhanced cooperation without requiring New Alexandrian resources or territorial expansion. | |||

The governments agreed to share intelligence regarding conditions in the claimed territory and to coordinate military operations during the initial security phase through [[Keltia Command]]. They further committed to explore joint logistics arrangements if mainland facilities could be restored, and to present the initiative to other [[Raspur Pact]] allies as coordinated action rather than unilateral Natopian expansion. | |||

==Announcement and Imperial blessing== | ==Announcement and Imperial blessing== | ||

===Private consultations=== | ===Private consultations=== | ||

In early IV.{{AN|1752}}, Chancellor [[Marco Lungo III]] and [[Pentheros]] [[Sergius Hergones]] traveled to [[Lindstrom]] for a private audience with [[Vadoma I|Empress Vadoma I]]. The Empress, confined by failing health, received them in her chambers at the [[Palace of Lindstrom]]. | |||

The delegation presented the case for restoration: the theological arguments developed by Church scholars, the strategic opportunity created by the [[Lower Jangsong Campaign]], the political moment following the [[1752 Natopian Frenzy elections|1752 elections]]. Vadoma listened attentively, reportedly asking pointed questions about logistics, sustainability, and the potential for Confederacy resistance. | |||

According to accounts later provided by participants, the Empress spoke at length about the [[Prophecy of Athlon]], the vision she had experienced fifteen years prior in the [[Great Temple of Bous]]. She spoke of the [[Butter Bull]]'s promise of transformation, of her conviction that Natopia's destiny remained unfulfilled. When she gave her blessing, witnesses reported that she did so with unusual firmness for one in declining health. | |||

===The formal proclamation=== | ===The formal proclamation=== | ||

On 20.IV.{{AN|1752}}, Chancellor Lungo III addressed the [[Frenzy|Frenzy of the Natopian Nation]] to announce the Elijahn Restoration. The proclamation declared Natopia's intention to ''"restore the sacred ground of Elijah's Rest to the protection of the Bovic faithful"'' and established the legal framework for the territorial claim. | |||

The proclamation emphasized the religious and humanitarian character of the initiative, characterizing it as ''"a sacred duty owed to our displaced brethren and the memory of Saint Elijah."'' It explicitly distinguished the claimed territory from areas under [[Bassaridia Vaeringheim|Bassaridian]] administration, noting that Natopia sought no conflict with recognized states. | |||

===Church endorsement=== | ===Church endorsement=== | ||

The [[Council of Metrobosarchs]] issued a formal endorsement on 25.IV.{{AN|1752}}, declaring the Elijahn Restoration ''"consonant with Bovic doctrine and the duties incumbent upon the faithful."'' [[Pentheros]] Hergones announced the appointment of Father [[Arsenios Kallistos]] as [[Metrobosarch of Keltia]], the first holder of that office who would actually reside in [[Keltia]] since the [[East Keltian Collapse]]. | |||

The [[Ayreon Tomb Guard]], which had remained in [[Hurmu]] guarding the evacuated [[Tomb of Elijah Ayreon]], received orders to prepare for redeployment. Members of the [[Holy Order of the Cult of Elijah]] dispersed across the [[Raspur Pact]] were invited to return to their ancestral monastery once it was secured. | |||

==Implementation== | ==Implementation== | ||

| Line 231: | Line 280: | ||

===Operation Sacred Ground=== | ===Operation Sacred Ground=== | ||

{{Main|Operation Sacred Ground}} | {{Main|Operation Sacred Ground}} | ||

[[File:Warrior of the Bovic Church Militant.jpg|250px|right|thumb|A warrior of the [[Bovic Church Militant]] in his war panoply, {{AN|1752}}.]] | |||

Following complex diplomatic manoeuvres in [[Aerla]], [[Mercury]], [[Moorland]], and [[Bassaridia Vaeringheim]], combined with an extensive logistical operation that rapidly assumed global dimensions, the deployment of the [[Raspur Pact|allied]] 300th Air-Land Combined-Arms Army to its starting position of [[Arctic Base Thorgils]] and Los Bananos would be declared to have been completed by 1 Natopuary (VIII) {{AN|1752}}. | |||

The transit agreement with [[Mercury]] proved particularly significant. Foreign Affairs Secretary [[Michelle Christophis]] negotiated unlimited peaceful passage rights through Mercurian airspace and territorial waters for the duration of the operation, securing emergency landing rights at Mercurian airfields and port access for logistical vessels. The agreement required a substantial financial consideration of ₦2.4 billion, paid from the defense allocations that Finance Secretary [[Prashant Chakravati]] had assured the [[Frenzy]] were sufficient for the operation. | |||

With deployment complete, the active phase, codenamed [[Operation Sacred Ground]], commenced. [[Nouvelle Alexandrie|New Alexandrian]] and [[Benacian Union|Benacian]] air strikes against positions held by [[Confederacy of the Dispossessed|the Dispossessed]] around [[Konungsheim]] began on 2.VIII.{{AN|1752}} and continued for six days. Air Wing Polaris from [[Arctic Base Thorgils]] conducted the majority of strike sorties, targeting identified Confederacy encampments, storage facilities, and defensive positions. The 24th Aviation (Strike) Regiment of the [[Benacian Union Defence Force]] conducted two full air raids against Konungsheim itself, striking a fortified compound in the ruins of the [[Monastery of the Holy Order of the Cult of Elijah]] that intelligence had identified as a Confederacy headquarters. | |||

====Air assault operations==== | |||

The air assault phase commenced at dawn on 8.VIII.{{AN|1752}}, employing [[Dingo-class shuttle|Dingo-class shuttles]] of the [[Natopian Spacefleet]]'s 60th Troop Carrier Group in a tactical role traditionally assigned to helicopters. The Dingo-class, designed for orbital-to-surface transport and logistics operations, possessed significantly greater speed, range, and payload capacity than conventional rotary-wing aircraft, though it had never been employed in contested air assault operations. Eighteen shuttles carried elements of the 11th Air Assault Brigade to simultaneous objectives at [[Konungsheim]] and [[Nordiskehjem]]. | |||

The assault plan assigned twelve shuttles to the primary objective at Konungsheim's abandoned international airport, with the remaining six targeting the port district of [[Nordiskehjem]] approximately 85 kilometres to the northwest. The Konungsheim assault force encountered only sporadic ground fire from Confederacy positions that had survived the preparatory bombardment. The initial landings proceeded without significant incident. Within two hours of touchdown, advance elements of the 11th Air Assault Brigade had secured the airport perimeter and established a defensive cordon. | |||

The Nordiskehjem assault encountered heavier than anticipated resistance. Confederacy forces in the area had dispersed into the surrounding terrain during the air campaign and were not as degraded as intelligence had assessed. As the six-shuttle formation approached the designated landing zone near the port, ground fire from concealed positions struck two of the descending craft. The shuttle ''Stampede Three'' suffered damage to its starboard thruster assembly and was forced to conduct an emergency landing approximately four kilometres short of the objective, coming down in rough terrain within [[the Green]]. The shuttle ''Stampede Five'' took multiple hits during its final approach and ditched in the harbour waters approximately 200 metres from the quayside. The remaining four shuttles completed their landings under fire and immediately established a perimeter, though the assault force was now significantly understrength. | |||

====Search and rescue==== | |||

The loss of two shuttles triggered immediate activation of search and rescue protocols. The ''Stampede Five'' crew, having ditched in the harbour, were recovered within hours by troops from the landed assault force who commandeered a small watercraft to reach the crash site. All eight crew members survived the water landing with minor injuries. | |||

The situation for ''Stampede Three'' was more precarious. The shuttle had come down in territory still contested by Confederacy forces. The fourteen personnel aboard, comprising six flight crew and eight assault troops, found themselves isolated in hostile terrain with functioning emergency beacons but limited defensive capability. The 17th Arctic Warfare Battalion at [[Arctic Base Thorgils]], part of Task Force "Thorgils," launched a rescue mission within three hours of the crash. | |||

A rescue force comprising two platoons of arctic warfare specialists, supported by medical personnel and a dedicated extraction team, departed AB Thorgils aboard four [[Raven-class shuttle|Raven-class shuttles]] escorted by fighters from Air Wing Polaris. The rescue force inserted approximately two kilometres from the crash site at dusk, then proceeded overland through the night to reach the downed shuttle. Contact with Confederacy fighters occurred twice during the approach march, with both engagements brief. The arctic warfare troops' superior training and night-fighting equipment proved decisive. | |||

The rescue force reached ''Stampede Three'' at approximately 0430 hours on 9.VIII.{{AN|1752}}, finding the crew and passengers alive and in defensive positions around the damaged shuttle. One assault trooper had sustained a serious leg wound from debris during the crash landing, but all personnel were ambulatory with assistance. Extraction proved challenging due to the rough terrain and the need to suppress a Confederacy patrol that had been tracking the rescue force. Air Wing Polaris provided close air support during the extraction, with precision strikes forcing the Confederacy fighters to disperse. By 0900 hours on 9.VIII.{{AN|1752}}, all personnel from ''Stampede Three'' had been evacuated to Arctic Base Thorgils. | |||

====Consolidation==== | |||

Following the search and rescue operation, attention returned to securing the primary objectives. Reinforcements from the 16 Air Assault Brigade arrived at Konungsheim airport on 9.VIII.{{AN|1752}}, substantially increasing the force available for security operations. The 6th "Nord" Brigade of the [[Constancian Foreign Legion]], having arrived via the maritime corridor, landed at Nordiskehjem the same day, bringing the assault force there up to strength and providing troops with particular expertise in arctic operations. | |||

Over the following days, combined Natopian and Constancian forces conducted methodical clearing operations through both Konungsheim and Nordiskehjem. Confederacy resistance proved less determined than the initial Nordiskehjem fighting had suggested. Many warbands, faced with the evident weight of force being deployed against them, chose to withdraw into [[the Green]] rather than engage in sustained combat. By 12.VIII.{{AN|1752}}, organised resistance in Konungsheim had effectively ceased, with remaining Confederacy fighters either fleeing northward or surrendering to advancing forces. | |||

The last significant engagement occurred on 14.VIII.{{AN|1752}} when a Confederacy rearguard was intercepted attempting to sabotage the main bridge connecting Konungsheim to its southern suburbs. The fighters were disarmed after a brief firefight that resulted in three Confederacy fatalities and no allied casualties. Nordiskehjem was declared secure on 15.VIII.{{AN|1752}}, though patrols in the surrounding area continued to encounter small groups of Confederacy stragglers for several weeks thereafter. | |||

The [[Bovic Church Militant]] began its ceremonial entry into Konungsheim on 16.VIII.{{AN|1752}}, with the [[Order of the Armored Goats]] and [[Ayreon Tomb Guard]] forming the vanguard of the procession, followed by warriors of the [[Order of the Super Secret Stripper Seekers]] and accompanying clergy. [[Metrobosarch of Keltia|Metrobosarch]] [[Arsenios Kallistos]] entered the city on 18.VIII.{{AN|1752}} and conducted the first Bovic service in the ruins of the [[Cathedral-Basilica of Eternal Slumber]] since its abandonment in {{AN|1737}}. The ceremony, broadcast via satellite link throughout [[Natopia]] and other [[Raspur Pact]] nations, marked the symbolic culmination of Operation Sacred Ground's initial phase. | |||

===The Stampede to Konungsheim=== | ===The Stampede to Konungsheim=== | ||

{{ | The "Stampede to Konungsheim" refers to the civilian resettlement phase of the Elijahn Restoration, named for the popular enthusiasm generated by Church and government announcements encouraging settlement of the reclaimed territory. The [[Dozan Bovic Church]] framed participation as a religious duty, an opportunity for the faithful to help prepare for the [[Butter Bull]]'s prophesied return by rebuilding the sacred sites of [[Elijah's Rest]]. The [[Marco Lungo III|Lungo III]] administration offered substantial material incentives, including land grants in the claimed bailiwicks, a five-year tax holiday for settlers, relocation assistance covering transportation and initial housing, and priority access to reconstruction contracts. | ||

Registration for the Stampede opened in VI.{{AN|1752}}, with initial settlement convoys scheduled to depart following military certification of secure conditions. By the end of VIII.{{AN|1752}}, approximately 12,000 Natopians had registered for resettlement. By 12.X.{{AN|1752}}, actual civilian arrivals totaled approximately 3,200 persons, well below initial projections. The discrepancy between registration and actual settlement reflects growing awareness of conditions in the reclaimed territory. | |||

The Stampede attracted diverse participants. [[Elijahn Rite]] faithful sought to return their community to its spiritual homeland, many of them descended from the 275,000 Norse refugees evacuated during [[Operation Northern Light]] in {{AN|1737}}. Economic migrants, attracted by land grants and development opportunities, saw frontier conditions as a chance to acquire property and establish businesses that would be unattainable in the settled demesnes of [[Tapfer]] and [[Arboria]]. Members of the [[Norse diaspora]] hoped to reconnect with ancestral territory, including some whose families had lived in Normark for generations before independence. Adventurers and speculators, drawn by the promise of a new frontier, rounded out the settler population. | |||

Church authorities established a vetting process to ensure settlers possessed either skills useful for reconstruction, such as engineering, construction, medicine, agriculture, and education, or demonstrated genuine religious commitment through membership in Elijahn Rite congregations. The process was intended to prevent the new territory from becoming a haven for criminals, fortune-hunters, and others who might undermine the restoration's religious character. Critics argued the screening was too restrictive and would slow resettlement. Supporters countered that without qualified personnel, the restoration would fail regardless of raw numbers. | |||

===Ecclesiastical restoration=== | ===Ecclesiastical restoration=== | ||

[[Metrobosarch of Keltia|Metrobosarch]] [[Arsenios Kallistos]] assumed residence in temporary quarters in Konungsheim in late VIII.{{AN|1752}}, establishing the first permanent Bovic ecclesiastical presence in [[Keltia]] since {{AN|1737}}. His immediate priorities included assessment of damage to sacred sites and development of a restoration plan for the [[Cathedral-Basilica of Eternal Slumber]] and [[Monastery of the Holy Order of the Cult of Elijah]]. | |||

Archaeological and preservation teams from the [[Dozan Bovic Church]] conducted initial surveys of the sacred sites in IX.{{AN|1752}}. The Cathedral-Basilica had suffered significant structural damage from fifteen years of neglect, with portions of the roof collapsed, the great rose window shattered, and water damage throughout the interior. Evidence of deliberate vandalism during the Confederacy occupation was also apparent, including the destruction of statuary and the defacement of religious imagery, though whether this represented anti-Bovic ideology or simple opportunism remained unclear. | |||

The Monastery was in marginally better condition, having been used by Confederacy forces as a headquarters. This occupation had motivated some minimal maintenance of the structure, though the interior had been stripped of religious furnishings and converted to military use. The monastery's famous library, containing centuries of theological manuscripts and the most complete collection of [[Elijahn Rite]] liturgical texts in existence, had been partially destroyed. Some volumes had apparently been used for fuel. Others were missing, their fate unknown. | |||

The [[Ayreon Tomb Guard]], having maintained vigil over the [[Tomb of Elijah Ayreon]] in [[Hurmu]] for fifteen years, received authorization to return to Konungsheim. A ceremonial detachment arrived in IX.{{AN|1752}}, though the Tomb itself remains in Huyenkula under Hurmu's custody by mutual agreement. The Guard's return represented symbolic continuity with the pre-collapse religious establishment, and their presence at the Cathedral-Basilica served to consecrate the site anew even in the absence of the physical relics. | |||

===Norse diaspora advisors=== | |||

A significant but often overlooked element of the restoration has been the contribution of advisors and consultants from the [[Norse diaspora]] settled in [[Moorland]] and [[Nouvelle Alexandrie]]. Many of these individuals, or their parents, had been among the 275,000 refugees extracted during [[Operation Northern Light]] in {{AN|1737}}. They possessed institutional memory of Normarkian systems, personal knowledge of the territory, and linguistic capabilities that native Natopians lacked. | |||

The [[Marco Lungo III|Lungo III]] administration engaged diaspora specialists beginning in V.{{AN|1752}}, during the planning phase. [[Moorland]] served as a particularly valuable source of expertise because of the substantial Normarker community that had settled there after the collapse. The Moorland government facilitated secondments of Normarker-background civil servants, engineers, and linguists to the Elijahn Development Authority. | |||

[[Nouvelle Alexandrie]] similarly provided specialists from its own Norse refugee population, many of whom had settled in the northern regions adjacent to the [[Boreal Air Bridge]] corridor. New Alexandrian Norse experts proved especially useful in interpreting pre-collapse documentation, many records being written in the Istvanistani-derived Norse administrative language that few mainland Natopians could read. | |||

As of X.{{AN|1752}}, approximately 180 diaspora advisors were working within the claimed territory or in support roles elsewhere. Their contributions included translation services for discovered documents, advice on local customs and expectations of the remnant population, identification of pre-collapse infrastructure that might be salvageable, and consultation on arctic construction techniques familiar from the old Kingdom. Several diaspora engineers had worked on the original infrastructure now being assessed, and their knowledge of system layouts and maintenance requirements has saved considerable reconnaissance effort. | |||

The diaspora advisors also served an important diplomatic function with the remnant population. While the Natopians arrived as liberators in their own view, the Norse remnant population had survived fifteen years without Natopian assistance. Diaspora intermediaries, who could speak to common heritage and shared loss, proved more effective at building trust than Natopian officials relying solely on religious authority. | |||

===Civilian reconstruction support=== | |||

{{Main|Elijahn Development Authority}} | |||

The [[Marco Lungo III|Lungo III]] administration established the [[Elijahn Development Authority]] under the [[Court of Commerce and Guilds]] to coordinate civilian reconstruction efforts. The EDA was given broad authority over infrastructure rehabilitation, economic development, and coordination with military authorities regarding security requirements for civilian activities. | |||

The first civilian specialists arrived at Konungsheim on 20.VIII.{{AN|1752}}, comprising engineers, infrastructure specialists, surveyors, and urban planners tasked with assessing the condition of pre-collapse facilities. Initial surveys revealed severe infrastructure degradation across all sectors. The findings were worse than anticipated. | |||

The Konungsheim international airport, while structurally sound, required complete restoration of its navigation systems, runway lighting, instrument landing equipment, and terminal facilities before it could support regular civilian traffic. The runway surface had cracked extensively from freeze-thaw cycles during the years without maintenance. The control tower had been stripped of all electronics. Snow removal equipment was rusted beyond repair. | |||

The port facilities at Nordiskehjem were in marginally better condition, having been used intermittently by Confederacy forces for smuggling operations. But the cargo handling equipment had been stripped for salvage. The fuel storage tanks were contaminated with water and biological growth. The quayside cranes had seized from corrosion. Ice damage to the harbor breakwaters would require repairs before the port could handle heavy cargo vessels. | |||

Municipal infrastructure had fared worst. The water treatment plant serving Konungsheim had failed entirely, with the remnant population that survived under Confederacy control relying on untreated well water and snowmelt. Electrical generation capacity was limited to a handful of diesel generators that the Confederacy had maintained for their own use. The city's electrical grid had suffered extensive damage from weather and neglect, with most distribution infrastructure requiring replacement rather than repair. Transportation networks, including the main highway connecting Konungsheim to Nordiskehjem and the railway line to the interior, had deteriorated without maintenance, with multiple bridge collapses and road washouts blocking major routes. | |||

The [[University of Doza]] dispatched scientific teams to assess environmental and health hazards, with particular attention to potential [[Northern Keltia respiratory syndrome]] persistence. NKRS had devastated Normark during {{AN|1737}}–{{AN|1738}}, contributing to the collapse by killing or incapacitating much of the population. Initial sampling found no evidence of active NKRS circulation, suggesting the pathogen had burned through the susceptible population and died out. The team recommended continued surveillance and mandatory health screening for all personnel entering the territory. | |||

[[Dingo Enterprises]], [[SATCo]], [[Neridia Defense Industries]], and the [[ESB Group]], expressed interest in reconstruction contracts, with preliminary discussions commencing in IX.{{AN|1752}}. The EDA estimated initial stabilisation costs at approximately ₦8.5 billion over the first two years, covering restoration of potable water supply, emergency repairs to the electrical grid, rehabilitation of port facilities at Nordiskehjem, establishment of a field hospital, and repairs to priority transportation routes. Longer-term reconstruction costs, including full restoration of the airport, railway rehabilitation, and reconstruction of the sacred sites, were estimated at ₦25–30 billion over the following decade. These figures remain subject to revision as assessment teams gather more detailed information. Several analysts have suggested the estimates are optimistic given the scope of damage documented. | |||

==Challenges== | |||

The Elijahn Restoration faces severe and compounding challenges that will test the [[Marco Lungo III|Lungo III]] administration's commitment and the [[Raspur Pact]]'s capacity for sustained support. As of 12.X.{{AN|1752}}, with the military phase concluded but the reconstruction barely begun, the scale of these challenges has become increasingly apparent. | |||

===The polar environment=== | |||

The single greatest obstacle to the restoration is the climate itself. The claimed territory lies in the polar and subpolar zones of northern [[Keltia]], with winter conditions comparable to the harshest regions on Micras. The construction season lasts approximately four months, from late spring to early autumn, during which major infrastructure work must be completed. Outside this window, temperatures drop so severely that concrete cannot cure, metal becomes brittle, and exposed workers risk frostbite within minutes of leaving heated shelters. | |||

The first winter in the reclaimed territory, from approximately XI.{{AN|1752}} through III.{{AN|1753}}, will be a critical test. The garrison and the civilian population, estimated at approximately 25,000 combined as of early X.{{AN|1752}}, must survive on supplies stockpiled during the brief construction season plus whatever can be airlifted in during winter months. Heating fuel alone represents an enormous logistical burden. Every building requires continuous heating to prevent pipes from freezing and structural damage from thermal stress. Pre-collapse Normark had an integrated heating infrastructure fed by a regional power grid. That system is non-functional. The replacement, diesel generators and fuel oil furnaces, requires continuous resupply. | |||

=== | Pack ice closes the maritime approaches to Nordiskehjem from approximately XII through IV. During these months, all resupply must come by air, either through [[Arctic Base Thorgils]] or via the [[Boreal Air Bridge]] corridor. AB Thorgils has a single runway that handles heavy transport aircraft. The runway capacity was designed for AB Thorgils' own needs, not for supplying a substantial mainland population. The EDA estimates that maintaining minimum supplies for 25,000 people through a six-month ice season requires average daily airlift capacity equivalent to twelve heavy transport sorties. This is achievable, but it leaves no margin for error. A prolonged storm closing AB Thorgils for even a week could create critical shortages. | ||

The cold also degrades equipment at alarming rates. Vehicles not equipped for arctic conditions suffer engine failures, hydraulic line ruptures, and fuel gelling. The [[Natopian Defense Force]]'s standard equipment was designed for the temperate climates of [[Tapfer]] and [[Arboria]]. Arctic-rated equipment exists, but in limited quantities, primarily in the units stationed at AB Thorgils and the [[Constancian Foreign Legion]]'s 6th "Nord" Brigade. The regular Natopian units rotating through the territory face a steep learning curve. | |||

===Logistical remoteness=== | |||

The claimed territory is among the most isolated positions the [[Raspur Pact]] has ever attempted to sustain. [[Konungsheim]] lies enormously far from Natopia's population centers and industrial base. The sea routes cross some of the most treacherous waters on Micras, subject to fierce storms, icebergs during the warmer months, and complete ice blockage during winter. Even in favorable conditions, supply convoys face weeks of transit through hostile seas. | |||

The logistics corridors established for [[Operation Sacred Ground]] rely on transit agreements with [[Mercury]] and [[Moorland]]. These agreements required substantial financial inducements and carry diplomatic implications. The ₦2.4 billion paid to Mercury for transit rights covered the operation's duration. Long-term sustainment will require either ongoing payments or renegotiated terms. Moorland has been cooperative, but its own resources are limited, and it cannot serve as a major staging area indefinitely. | |||

The [[Boreal Air Bridge]] alternative route, through [[New Blackstone]] and [[Arctic Base Thorgils]], is longer and more expensive per ton of cargo delivered. It also depends on continued access to New Blackstone facilities, which involves another set of diplomatic considerations. | |||

Supply chain vulnerability is inherent in any position this remote. A single point of failure, closure of AB Thorgils due to weather, diplomatic difficulties with transit nations, mechanical failure in a critical cargo aircraft, can cascade into supply shortages. The [[Einhorn Society]]'s criticism that the territory would be ''"even more reliant upon the overextended Boreal Air Bridge than the old Kingdom had been"'' reflects this fundamental geographic reality. | |||

The [[Arboria|Government of Northern Arboria of the Principality of Arboria]] was particularly helpful, costs for this operation having been guaranteed by their Princess, even through her personal funds, as needed. Merchant shipping was procured and marshaled at Tirlar. | |||

===Infrastructure degradation=== | |||

Fifteen years of abandonment in an arctic climate have left the pre-collapse infrastructure in worse condition than even pessimistic assessments had predicted. The EDA's surveys through IX and X.{{AN|1752}} documented systematic failure across all sectors. | |||

Roads and bridges deteriorated fastest. The freeze-thaw cycle, which causes water infiltration into cracks that then expands as ice, destroys pavement within a few years without maintenance. The main highway connecting Konungsheim to Nordiskehjem had seventeen bridge collapses or partial failures along its 85-kilometre length. The railway line to the interior, which once connected Konungsheim to the broader Normarkian network, suffered at least twenty-three track washouts where streams had undermined the roadbed. | |||

Buildings fared variably depending on construction quality and whether they had been occupied during the Confederacy period. Structures with intact roofs generally survived, though interior finishes were often destroyed by moisture and temperature cycling. Structures with roof damage, even minor damage, suffered catastrophic interior destruction as water and ice invaded. The Cathedral-Basilica of Eternal Slumber, with multiple roof collapses, has extensive structural damage that some engineers believe may make full restoration impractical. They have suggested that preserving certain elements within a new structure might be more feasible than attempting authentic reconstruction. | |||

Utilities present the most urgent challenges. The water treatment plant's failure means the entire urban population depends on improvised supplies. Bottled water airlifted from AB Thorgils, supplemented by boiled snowmelt when transport capacity is constrained, currently serves the population. This is unsustainable long-term. A new water treatment facility must be operational before the population can grow significantly, but construction in arctic conditions takes years. | |||

===Security concerns=== | |||

The military victory over the [[Confederacy of the Dispossessed]] warbands in VIII.{{AN|1752}} did not eliminate the Confederacy as a security threat. The warbands withdrew into [[the Green]] rather than being destroyed. Their fighters, estimated at 2,500–3,000 after casualties from Operation Sacred Ground, remain somewhere in the wilderness beyond the secured perimeter. | |||

These forces lack the strength to challenge Natopian military positions directly. But they retain capability for guerrilla operations, raids on supply convoys, and attacks on isolated settlements. The harsh climate cuts both ways in this regard. Winter weather constrains Confederacy operations as it does Natopian ones. But local fighters possess experience with arctic conditions that many Natopian troops lack. They know the terrain, have caches of supplies established over fifteen years of occupation, and can survive in conditions that would kill unprepared outsiders. | |||

Patrols throughout IX and X.{{AN|1752}} encountered small groups of Confederacy stragglers, some of whom surrendered peacefully and others who fled. The EDA designated certain reconstruction projects as requiring military escort due to their exposure to potential attack. Survey teams working more than five kilometres from secured areas travel with armed guards. | |||

The long-term security situation depends on whether the Confederacy warbands coalesce into a renewed threat or fragment further. Intelligence assessments as of X.{{AN|1752}} suggest the latter is more likely. The warbands had no unified command before Operation Sacred Ground and are unlikely to develop one now, especially with their largest formations destroyed or scattered. But even dispersed raiders can make life dangerous for isolated settlers and construction crews. | |||

===Sustainability questions=== | |||

The fundamental question hanging over the Elijahn Restoration is whether Natopia can sustain the effort long enough for it to succeed. The immediate military operation was achievable. The short-term humanitarian response, providing emergency support to the remnant population and the initial wave of settlers, is manageable. But the long-term reconstruction, the work of years and decades required to make the territory self-sustaining, represents a commitment of resources far exceeding anything in the operation's first year. | |||

The ₦25–30 billion reconstruction estimate, even if accurate, represents a substantial portion of Natopia's discretionary spending capacity over a decade. This spending must compete with other priorities: military modernization, infrastructure maintenance in the existing demesnes, social programs, debt service. The [[Free Juice and Bagels Party|FJBP]]-[[Parti Alexandrin]] coalition has a working majority in the [[Frenzy]], but electoral dynamics could change. A future government less committed to the restoration could reduce funding, slow timelines, or abandon the project entirely. | |||

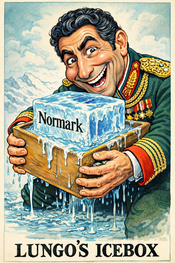

Former Chancellor [[Emmanuel Aristarchus]]'s derisive nickname for the initiative, "[[Lungo's Icebox]]," reflects a line of criticism that may grow if costs escalate or progress stalls. The withdrawal from [[Whales]], which Aristarchus himself orchestrated, was justified partly on grounds of eliminating an expensive territorial commitment. Critics argue the restoration creates a new and more expensive one. | |||

Supporters counter that the religious significance of Elijah's Rest justifies exceptional commitment, that strategic value in northern Keltia outweighs financial costs, and that demonstrating Natopia's resolve after years of perceived retreat serves broader national interests. Whether these arguments will sustain political support through years of difficult and expensive reconstruction remains to be seen. | |||

The [[Imperial Constancian Government]] pledged ₦1 billion outright to aid in the reconstruction costs, with an additional ₦1 billion provided personally by the Imperial family. | |||

===The remnant population=== | |||

Between several hundred thousand and possibly one million people survived fifteen years of Confederacy rule or stateless chaos in the claimed bailiwicks. Initial contact with this population has been mixed. | |||

Some remnants welcomed the Natopians as liberators, particularly those who had suffered under Confederacy exploitation. Others adapted to survival strategies that may not align with the restoration's goals. Informal power structures emerged during the years of abandonment. Local strongmen, community leaders, and various intermediaries established ways of getting by that the incoming administration may disrupt. | |||

Some collaborated actively with Confederacy forces. Identifying collaborators and determining appropriate responses, justice versus reconciliation, presents political and practical challenges. Former collaborators often possess useful local knowledge but may face hostility from their neighbors. | |||

The relationship between the remnant Norse population and the predominantly non-Norse Natopian settlers remains undefined. The settlers arrive with religious motivation, state backing, and access to resources. The remnants survived fifteen years without help, developed their own ways, and may resent newcomers claiming authority over territory the remnants never really left. The Norse diaspora advisors serve as intermediaries, but their primary loyalty is to the Natopian project, not to the remnants who chose, or were forced, to stay behind. | |||

===Border with Bassaridia Vaeringheim=== | |||

The [[Natopian Clarification on Operation Sacred Ground]] addressed immediate concerns about transit routes and territorial recognition with [[Bassaridia Vaeringheim]], but the two powers now share a land frontier in a region where borders have historically been fluid. | |||

The claimed territory abuts Bassaridian Normark along an undefined boundary in the eastern bailiwicks. Pre-collapse internal administrative borders do not necessarily correspond to defensible terrain features. Neither government has stationed significant forces along this border, but incidents involving civilian movement, economic activity, or patrol encounters could generate friction. The relationship between Natopia and Bassaridia Vaeringheim is not hostile, but neither is it particularly warm. Both powers may find their interests diverging as the region develops. | |||

==The Confederacy question== | ==The Confederacy question== | ||

The [[Confederacy of the Dispossessed]] had established varying degrees of control over the claimed bailiwicks during the fifteen years following the [[East Keltian Collapse]]. Unlike the eastern and central portions of former [[Normark]], where organised Normarkian resistance forces had continued fighting until their destruction in the [[Lower Jangsong Campaign]], the southwestern bailiwicks experienced a more fragmented occupation. Multiple warbands, owing nominal allegiance to the Confederacy but operating largely independently, had carved out territories of varying size and stability. | |||

Intelligence assessments prior to [[Operation Sacred Ground]] estimated total Confederacy strength in the Konungsheim and Nordiskehjem areas at approximately 3,300 fighters of varying quality, organised into at least seven distinct warbands without unified command. Some of these warbands had established relatively stable control over specific areas, extracting tribute from remnant populations and maintaining basic order. Others operated as pure raiders, moving through the territory opportunistically. The largest warband, estimated at approximately 800 fighters, had established its headquarters in the [[Monastery of the Holy Order of the Cult of Elijah]], using the fortified structure as a base for operations throughout the Konungsheim bailiwick. | |||

The six-day air campaign and subsequent ground operations inflicted approximately 85 fatalities on Confederacy forces, with approximately 400 additional fighters captured or disarmed during clearing operations. The warband headquartered at the Monastery suffered disproportionate casualties during the air campaign, with its leadership apparently killed in the strikes that preceded the ground assault. The majority of Confederacy personnel, however, withdrew into [[the Green]] ahead of advancing forces rather than engaging in sustained combat. This withdrawal preserved their strength but ceded the urban areas to Natopian control without a prolonged fight. | |||

The defeated warbands present an ongoing security concern. While they lack the strength to challenge the Natopian military presence directly, they retain capability for guerrilla operations, raids on supply convoys, and attacks on isolated settlements. Security forces continue patrol and reconnaissance operations in the countryside beyond the secured urban areas. | |||

==Reactions== | ==Reactions== | ||

| Line 250: | Line 437: | ||

===Domestic=== | ===Domestic=== | ||

[[File:LungosIcebox1752NAT.png|175px|thumb|right|A pro-Aristarchus publication in [[Klaasiya]], the ''[[Natopian Jester]]'' took Aristarchus' nickname of [[Lungo's Icebox]] and plastered it in all the political cartoons it could, doubling its circulation overnight; {{AN|1752}}.]] | [[File:LungosIcebox1752NAT.png|175px|thumb|right|A pro-Aristarchus publication in [[Klaasiya]], the ''[[Natopian Jester]]'' took Aristarchus' nickname of [[Lungo's Icebox]] and plastered it in all the political cartoons it could, doubling its circulation overnight; {{AN|1752}}.]] | ||

====Free Juice and Bagels Party==== | ====Free Juice and Bagels Party==== | ||

The governing [[Free Juice and Bagels Party]] rallied behind Chancellor [[Marco Lungo III]]'s initiative. FJBP Whip [[Theodora Simonides]] described the Restoration as "a defining moment for this administration and for our party's renewal," emphasizing that the FJBP had returned to its traditional role as the party of Natopian confidence and purpose. Finance Secretary [[Prashant Chakravati]] assured the [[Frenzy]] that the Treasury had accounted for the operation's costs within existing defense allocations | The governing [[Free Juice and Bagels Party]] rallied behind Chancellor [[Marco Lungo III]]'s initiative. FJBP Whip [[Theodora Simonides]] described the Restoration as "a defining moment for this administration and for our party's renewal," emphasizing that the FJBP had returned to its traditional role as the party of Natopian confidence and purpose. Finance Secretary [[Prashant Chakravati]] assured the [[Frenzy]] that the Treasury had accounted for the operation's costs within existing defense allocations. Foreign Affairs Secretary [[Michelle Christophis]] highlighted the coordination with [[Nouvelle Alexandrie]] as evidence of the administration's recommitment to [[Raspur Pact]] partnership. | ||

Former Chancellor [[Emmanuel Aristarchus]], however, broke ranks with his former party. Speaking to reporters outside his [[Klaasiya]] residence, the architect of the [[Natopian Withdrawal from Whales]] and [[Universal Compact]] offered characteristically sharp criticism: ''"When I suggested Natopia focus on its own affairs, I was called an isolationist and a disgrace. Now young Lungo wants to plant flags on sacred ground fifteen years abandoned to the Green, and suddenly imperial adventure is patriotic duty. The only difference I can see is that this time the Church is blessing the overreach."'' Aristarchus dismissed the initiative as "[[Lungo's Icebox]]," predicting it would become a frozen money pit that would drain the Treasury for generations. The former Chancellor, who lost his [[Frenzy]] seat in the [[1748 Natopian Frenzy elections|1748 elections]] and was subsequently removed as party leader, has remained a vocal critic of FJBP leadership since his political exile. | Former Chancellor [[Emmanuel Aristarchus]], however, broke ranks with his former party. Speaking to reporters outside his [[Klaasiya]] residence, the architect of the [[Natopian Withdrawal from Whales]] and [[Universal Compact]] offered characteristically sharp criticism: ''"When I suggested Natopia focus on its own affairs, I was called an isolationist and a disgrace. Now young Lungo wants to plant flags on sacred ground fifteen years abandoned to the Green, and suddenly imperial adventure is patriotic duty. The only difference I can see is that this time the Church is blessing the overreach."'' Aristarchus dismissed the initiative as "[[Lungo's Icebox]]," predicting it would become a frozen money pit that would drain the Treasury for generations. The former Chancellor, who lost his [[Frenzy]] seat in the [[1748 Natopian Frenzy elections|1748 elections]] and was subsequently removed as party leader, has remained a vocal critic of FJBP leadership since his political exile. | ||

| Line 266: | Line 454: | ||

===International=== | ===International=== | ||

The [[Einhorn Society]] declined to support the incursion into the former territory of [[Normark]], citing the fundamentally unsustainable position of the envisioned territory, which would be even more reliant upon the | The [[Einhorn Society]] declined to support the incursion into the former territory of [[Normark]], citing the fundamentally unsustainable position of the envisioned territory, which would be even more reliant upon the overextended [[Boreal Air Bridge]] than the old Kingdom had been before the [[East Keltian Collapse]]. | ||

Initial proposals in [[Constancia]] to deploy Normarker exiles from the [[510th (Shahzamin) Army]] in support of the Natopian invasion had been countered by remonstrations concerning the fundamental unsuitability of the Home Guard for expeditionary warfare. Counterproposals involving the [[Constancian Foreign Legion]] were hurriedly worked up by the Imperial General Staff of the [[Imperial Constancian Armed Forces|Armed Forces]]. Plans eventually consolidated around the deployment of the 6th "Nord" Brigade with key logistical enablers contracted to the Security Directorate of the [[Honourable Company]]. | Initial proposals in [[Constancia]] to deploy Normarker exiles from the [[510th (Shahzamin) Army]] in support of the Natopian invasion had been countered by remonstrations concerning the fundamental unsuitability of the Home Guard for expeditionary warfare. Counterproposals involving the [[Constancian Foreign Legion]] were hurriedly worked up by the Imperial General Staff of the [[Imperial Constancian Armed Forces|Armed Forces]]. Plans eventually consolidated around the deployment of the 6th "Nord" Brigade with key logistical enablers contracted to the Security Directorate of the [[Honourable Company]]. | ||

| Line 273: | Line 461: | ||

The [[Benacian Union]] offered the deployment of four logistical support regiments and an area defence regiment to [[Los Bananos]] once the scale of the Natopian operation became apparent. | The [[Benacian Union]] offered the deployment of four logistical support regiments and an area defence regiment to [[Los Bananos]] once the scale of the Natopian operation became apparent. | ||

====Bassaridia Vaeringheim==== | |||

{{Main|Bassaridian response to Operation Sacred Ground|Natopian Clarification on Operation Sacred Ground}} | |||

[[Bassaridia Vaeringheim]], having recently consolidated control over eastern and central former [[Normark]] following the [[Lower Jangsong Campaign]], issued formal concerns regarding the operational planning documents that had mentioned potential transit routes through Bassaridian-administered corridors. The [[Natopian Clarification on Operation Sacred Ground]] addressed these concerns, explicitly distinguishing the Natopian claim from Bassaridian-held territory and confirming that all logistics corridors would avoid Bassaridian airspace and waters. | |||

==Current status (12.X.1752)== | |||

As of 12.X.{{AN|1752}}, the Elijahn Restoration has completed its military phase and entered the more challenging reconstruction period. | |||

The security situation in the claimed bailiwicks is stable but not resolved. Natopian and allied forces control Konungsheim, Nordiskehjem, and the main transportation corridors between them. Confederacy remnants have withdrawn beyond effective patrol range. No major security incidents have occurred since late VIII, though minor encounters with small groups of stragglers continue. | |||

The civilian population in the claimed territory consists of approximately 25,000 persons: roughly 8,000 military and security personnel, 3,200 settlers from the Stampede to Konungsheim, several thousand reconstruction workers and contractors, and an estimated remnant population of 12,000–15,000 in and around the secured urban areas. The remnant population figure is provisional; accurate census data will take months to compile. | |||

Infrastructure rehabilitation has begun on priority projects. Emergency water purification systems are operational, providing treated water to approximately 60% of the Konungsheim population. Portable generators supply electricity to essential facilities. Road repairs have opened the main Konungsheim-Nordiskehjem highway to light traffic, though load limits restrict heavy vehicles. The port at Nordiskehjem has received emergency repairs to two berths and can now handle medium-sized cargo vessels, weather permitting. | |||

The reconstruction timeline remains uncertain. The first full winter has not yet arrived. How the territory fares from XI.1752 through III.1753 will determine whether the reconstruction schedule is realistic or requires substantial revision. The EDA is stockpiling supplies in anticipation of the ice season, but capacity constraints mean the margin for error is thin. | |||

Religious ceremonies continue at the [[Cathedral-Basilica of Eternal Slumber]] despite its damaged state. [[Metrobosarch of Keltia|Metrobosarch]] [[Arsenios Kallistos]] has announced plans for a major reconstruction appeal to Bovic faithful across the Raspur Pact, seeking donations to fund restoration of the sacred sites. The appeal has generated modest initial response; whether sustained giving materializes depends partly on whether the restoration demonstrates long-term viability. | |||

The Elijahn Restoration remains in its early stages. The initial military victory was the easy part. The reconstruction will take decades. Whether Natopia possesses the political will and material resources to see it through is the question that will determine the restoration's ultimate success or failure. | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| Line 293: | Line 500: | ||

* [[Arsenios Kallistos]] | * [[Arsenios Kallistos]] | ||

* [[Operation Sacred Ground]] | * [[Operation Sacred Ground]] | ||

* [[Dingo-class shuttle]] | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Latest revision as of 06:45, 21 January 2026

| Elijahn Restoration aka Operation Sacred Ground |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Aftermath of the East Keltian Collapse | |||||||

Natopian territorial claim in southwestern former Normark, 1752 AN. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Various (fragmented command) |

||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Confederacy militias (fragmented, no unified command) |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Estimated division-level strength ~21,600 personnel Constancian brigade ESB logistics support | Estimated 3,300 fighters (varying quality; Konungsheim and Nordiskehjem areas) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 0 killed 13 wounded 2 Dingo-class shuttles lost | ~85 killed (est.) Unknown wounded ~400 captured/disarmed |

||||||

| Military operations coordinated with civilian "Stampede to Konungsheim" settlement initiative | |||||||

The Elijahn Restoration, also known by its military designation Operation Sacred Ground, is a territorial claim and settlement initiative launched by the Bovic Empire of the Natopian Nation in 20.IV.1752 AN to reclaim portions of the former Kingdom of Normark abandoned during the East Keltian Collapse of 1737 AN. The claim encompasses eight former Norse bailiwicks, collectively termed Elieland, along the southwestern coast. These include the former capital of Konungsheim (known in Natopian tradition as Elijah's Rest) and the port settlement of Nordiskehjem, with a combined pre-collapse population of approximately 4.1 million.

The initiative draws from religious obligation, strategic opportunity, and domestic political need. The Dozan Bovic Church endorsed the restoration on theological grounds, arguing that 139 years of proximity to the remains of Saint Elijah Ayreon consecrated the ground of Konungsheim itself, and that the Prophecy of Athlon demands the faithful prepare for the Butter Bull's return. Strategically, the claim expands Raspur Pact presence in northern Keltia and complements Nouvelle Alexandrie's Arctic Base Thorgils on nearby Los Bananos. Politically, the Lungo III government sought to demonstrate renewed national purpose following the controversies of the Aristarchus years.

Military operations commenced in VIII.1752 AN, with Konungsheim and Nordiskehjem secured within two weeks. Pentheros Sergius Hergones announced that Father Arsenios Kallistos, a priest of the Phallic Cult, would serve as the new Metrobosarch of Keltia, the first holder of that office to actually reside in Keltia since the collapse. As of 12.X.1752 AN, the military phase has concluded, but the civilian reconstruction effort faces severe challenges. The region's polar climate, its extreme remoteness from Natopian supply centers, and fifteen years of infrastructure decay combine to make the restoration's long-term viability uncertain.

Background

Natopia's connection to the Normark region predates the Kingdom of Normark itself. In 1615 AN, the demigod Athlon took charge of the abandoned city of Konungsheim and renamed it Elijah's Rest, initiating Natopian settlement in northern Keltia. The region grew under Natopian administration. In 1649 AN it was formalized with the establishment of the Elian Union as a super-demesne encompassing Elijah's Rest, Normark, the Kingdom of Leng, the Viceroyalty of The Two Martyrs, and the Duchy of New Aquitane.

Normark was established as a distinct Natopian demesne in 1657 AN. The territory remained under Natopian sovereignty until 1678 AN, when a referendum approved transfer to Elwynn. Normark subsequently passed through Elwynnese administration, survived the Second Elwynnese Civil War, and achieved independence in 1703 AN under King Tarjei Thorgilsson. Throughout these transitions, the Natopian cultural and religious imprint remained significant, particularly in the veneration of Saint Elijah Ayreon.

The sacred sites of Konungsheim

Konungsheim became a center of Bovic pilgrimage following the interment of Elijah Ayreon in 1598 AN. Prince Elijah, husband of Nathan, had been martyred by Siseran cultists in Walstadt. His grieving widower Nathan arranged for the remains to be brought to Normark, where they rested in what became the Tomb of Elijah Ayreon.

Over the following century and a half, significant religious infrastructure developed around the tomb. The Cathedral-Basilica of Eternal Slumber served as the seat of the Metrobosarch of Keltia, one of the senior hierarchs of the Dozan Bovic Church. The Monastery of the Holy Order of the Cult of Elijah housed the monastic order dedicated to Saint Elijah's veneration. The Ayreon Tomb Guard, a military order, was charged with protecting the sacred remains.

The city also gave its name to the Elijahn Rite, a distinct tradition within Bovinism emphasizing the worship of Saint Elijah. The rite proved particularly popular in territories with Ayreonist heritage.

The Phallic Cult and Saint Elijah

The Phallic Cult, a mystery religion established in 1573 AN by Pentheros Nathan Waffel-Paine (as Theodores Athanatos), maintains a distinctive relationship with Saint Elijah's memory. Elijah appears in the Phallic pantheon alongside Bruno, Priapus, and the Winged Phallus, honored as patron of romantic love. The Apotheosis of Elijah, describing Nathan's deification of his martyred husband, constitutes the sole Tetrabiblical reference to the Phallic mysteries.

The Cult's emphasis on masculine virtues, assertive action, and sacred aspects of virility proved significant in the theological arguments advanced for the restoration.

East Keltian Collapse (1737)