Mango Anarchy

| The Mango Anarchy Shirerithian Revolutionary Era |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Shiro-Benacian War | ||||||||

The Revolutionary Committee of Shirekeep, under guidance of self-appointed Prefect Erasmo Laegel and in the presence of Kaiseress Salome, proclaimed the end of Imperial Power. Stripping her from her last influence and power, against the wishes of the government in Novi Nigrad. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

|

|

||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

|||||||

The Mango Anarchy, also known as the Shirerithian Revolutionary Era, marked one of the most tumultuous and transformative periods in recent Shirerithian history. This era began with a silent coup orchestrated by Steward Louis Thuylemans against the Kaiseress, following her decision to launch the infamous Bad Neighbour II nuclear attack, which ignited deep unrest within the empire and heightened international tensions. The subsequent period was defined not only by the internal power struggle between reformists and reactionaries but also by the widespread civil and military conflicts that accompanied the unfolding of the Shiro-Benacian War and various regional rebellions and conflicts.

Background and Causes

Shiro-Benacian Cold War

The Shiro-Benacian Cold War, which took place between 1707 and 1733 AN, was a period of intense geopolitical rivalry between the Imperial Republic of Shireroth and the Benacian Union, two dominant powers within the Raspur Pact. This conflict, which began as a struggle for influence and dominance in the aftermath of the Kalirion Fracture, escalated into a hot war in 1733 AN. The consequences of this war directly contributed to the waning influence of Kaiseress Salome and the chaotic period known as the Mango Anarchy.

The roots of the cold war lay in the ideological and territorial divisions that emerged following the Kalirion Fracture. Shireroth, struggling to recover from the political fragmentation of its empire, viewed the rise of the Benacian Union - an alliance of Humanist regimes led by the Unified Governorates from the ruins of Imperial Republic's territories - as an existential threat to its sovereignty and aspirations for regional dominance.

Tensions further escalated during the 1710s, fueled by Shirerithian dissatisfaction with the Benacian Union’s growing economic and political influence within the Raspur Pact. The election of anti-Pact politicians in 1717 AN signaled Shireroth's desire to assert greater independence. Over the next two decades, mutual distrust manifested in proxy conflicts, economic competition, and an escalating arms race, culminating in the Sathrati Emergency, Shireroth's final indirect victory before the outbreak of full-scale war.

Sathrati Emergency

The Sathrati Emergency was a critical conflict in the late stages of the Shiro-Benacian Cold War, occurring from 1730 to 1732 AN in the Emirate of Sathrati, a key overseas territory of the Imperial Republic of Shireroth. The emergency was sparked by a pro-Benacian insurgency by the Council of Sathrati that sought to stop the increasing involvement of Shirekeep into its regional affairs. Fears of an imminent Shirerithian intervention to overturn the Protocols of Erudition and depose the Council, led to the Council's issueing of the Declaration of Preparedness, which was interpreted as a de facto declaration of war.

Faced with a rapidly deteriorating situation, Shireroth deployed a significant military force, including elite units from the Imperial Forces and the Imperial Navy, to suppress the uprising. The campaign was marked by intense urban combat, counter-insurgency operations, and widespread use of air and naval power to isolate rebel forces. Shireroth also imposed harsh martial law, which temporarily restored order but deepened resentment among parts the local population. The Council of Sathrati was replaced by a newly appointed one, under direct authority of the Golden Mango Throne.

Shiro-Benacian War

By 1733 AN, tensions had reached a breaking point. A series of provocations—including the Malak Stadium Massacre and the Shirekeep Rocket Attacks, ignited the Shiro-Benacian War: a total war fought across multiple continents

Debt Issues

In the years leading up to the Mango Anarchy, the debt crisis emerged as a central, unresolved challenge that would ultimately destabilize the Imperial Government and weaken its authority across Shireroth. While the government had managed to keep spending under control following the Auspicious Occasion through aggressive budget cuts, the rapid expansion of the empire soon stretched its financial resources thin once more. With the empire's reach growing across Micras, costs skyrocketed: maintaining the increasingly opulent court at Raynor's Keep to satisfy the nobility’s demands, integrating new territories and their associated armies, and managing the extensive imperial bureaucracy all became unsustainable.

The Erb currency, originally pegged to wheat during the reign of Kaiseress Salome, initially served as a reliable standard. However, as the empire grew in size and complexity, the limitations of a purely agrarian-backed currency became apparent. The Erb’s rigid structure could not keep pace with Shireroth’s expanding economic demands or effectively support the financial strain of maintaining the empire’s reach over a diverse and distant population.

The debt problem was exacerbated by looming foreign debt repayments owed primarily to Natopia and Nouvelle Alexandrie, key creditors whose loans had propped up previous government programs and military expenditures. Yet, despite the looming repayments, the imperial government remained unwilling to drastically reduce spending. This resistance stemmed largely from escalating tensions with the Benacian Union, in preparation for a potential war, the government felt it could not risk scaling back on military funding or strategic infrastructure projects.

Even more concerning than the sheer size of the debt - which was not larger than that of the neighbouring Benacian Union - was Shireroth’s chaotic fiscal system. Noble privileges, feudal exemptions, and a labyrinth of archaic tax codes left the treasury struggling to maintain consistent revenue streams. Many powerful fiefs and noble families maintained tax privileges and exemptions dating back to the early feudal period, which left significant portions of the empire’s wealth untapped. Without the authority to overhaul these deeply entrenched systems, the imperial treasury remained vulnerable, as evidenced by Rigobert Brunswick, the Commissioner for the Fiscus, who warned in 1730 AN that without urgent reforms, an economic shock—such as war—could send the empire’s finances into a dangerous downward spiral.

This warning was validated with the outbreak of the Sathrati Emergency and eventually the Shiro-Benacian War in 1733 AN, events that set off a financial crisis. Despite desperate attempts to contain costs, the government had to resort to cuts in social programs (the popular Grain Program in the Eastern Imperium were entirely slashed and became dependent on the goodwill of the local governments) to fund the war effort, which spurred resentment among the lower classes. By 1737 AN, the government’s financial position was untenable, leading Shireroth to default on its debt obligations. This default not only damaged Shireroth’s reputation among foreign creditors but also led to social unrest, as the court’s ostentatious spending and noble privileges were widely resented by commoners who bore the brunt of the austerity measures.

Faced with imminent bankruptcy and a crumbling financial system, revolutionary leaders within the Revolutionary Committee of Shirekeep began searching for ways to stabilize the economy. One of the most notable measures was the introduction of assignats, a form of paper money backed by land and resources confiscated from nobles and royal estates, in an attempt to create liquidity and maintain basic government functions. While the assignats provided a temporary respite, they also represented a significant departure from traditional monetary practices, which alarmed conservatives.

Bad Neighbour II

Operation Bad Neighbour II was a controversial and devastating Shirerithian military operation conducted during the early stages of the Shiro-Benacian War in 1733 AN. Ordered personally by Kaiseress Salome, the operation involved the deployment of nuclear weapons against key infrastructure targets within the Benacian Union. If the strikes would have been better prepared and not taken the Shirerithian government and military apparatus aback - with exception of some close and powerful military figures to Salome -, it could have been seen as an attempt to disrupt the Union's ability to wage war by crippling its industrial and logistical capabilities. The operation, ordered by the Kaiseress, however would mostly anger officials in her own government and lead many to think that she had lost her mind when her children had died, with her just abiding time to strike.

Crisis of the Old Regime (1733-1735)

"The Kaiseress is Tired"

As the hours ran out on the Benacian 48-hour nuclear ultimatum, Thuylemans cabinet became increasingly concerned for the consequences. After their daily meeting with Salome on 2.XII.1733 AN, they learned that the Kaiseress had ordered an increase in Bad Neighbour II's tempo, and that it was to begin targeting locations in Holwinn and Monty Crisco as well; this would be in order to support Operations Green Shield and Red Shield respectively. The Kaiseress had also isolated Bad Neighbour II from the command structure of the Ministry of Military Affairs, officiating what she had begun when she circumvented the chain of command to initiate Hiericus and begin the war.

Once news had arrived on casualties in the Benacian Union strike on Lichkeep, Thuylemans received a private visit from one Tribune Herzl, indicating that a portion of 1. Legion was with him and his interest in stopping the nuclear war. The firestorm had burned through neighborhoods containing many of their families. Another hit, possibly on the city center itself would literally mean a devastating blow to the Imperial Government.

Recognizing the critical situation and the imminent threat of a full-scale nuclear war, Thuylemans made a bold and decisive move. He ordered Tribune Herzl of the 1. Legion to put Kaiseress Salome under house arrest, attempting to halt the escalating conflict. The ensuing confrontation in Raynor's Keep was intense, with fighting erupting between the Palatini and the Legionnaires in the small corridors of the Keep. Salome-loyalists fiercely defended the Kaiseress, but they were met with equally determined guards who were loyal to the Steward - or at least fond of the idea to not see their families die in nuclear hellfire - and who had lost family members in the Benacian counterattack. The battle was fierce but short-lived. The guards loyal to the Steward, driven by a desire to prevent further devastation, managed to overpower Salome's defenders and secure a victory for the coup.

Following the coup's success, the Kaiseress was taken to Mahamantot Bunker, which offered more safety than a castle which served as a target for Benacian artillery fire, where she was brought face-to-face with the Steward. In this tense and pivotal meeting, she received an informal declaration outlining the terms of her new role and the transfer of power:

- Cessation of Real Power: Salome would no longer wield any real power over the government. This effectively granted the Steward control over the Armed Forces, ensuring that military operations would be conducted under more cautious and calculated leadership. This arrangement would remain until the situation had improved and a suitable successor was groomed and deemed trustworthy enough not to unleash nuclear devastation.

- Spiritual Leadership: The Kaiseress was to take up a more active role in the spiritual guidance of her people. She would work to cooperate with existing religious institutions, such as the Batavian Catologian Church and various cults like Tianchaodao, aiming to bring them closer to the Imperial Cult. This new responsibility would allow her to contribute to the nation's well-being in a non-military capacity, fostering unity and moral resilience among the populace.

- Public Reassurance and Diplomacy: To prevent further panic and to stabilize the internal situation, the Kaiseress would make public appearances and speeches, reassuring the citizens and the international community of the Empire's commitment to peace and reconstruction and commit to supporting any future convention against nuclear warfare. She would serve as a figurehead of continuity and hope, while the Steward handled the practical aspects of governance and military strategy.

In the eyes of the public, the Kaiseress remained in charge of daily affairs. However, shortly after the coup, the cabinet decided to move southwards, further away from the frontlines, to ensure the safety and continuity of the government's functions. Salome remained in the capital, guarded by a group of Legionnaires, and made impossible to throw around orders. This move ensured that while Salome was still the symbolic leader, the real power resided with the Steward and the cabinet, who could now try to act decisively.

Relocation of the Shirerithian Government

In 1734 AN, the outbreak of the Maltenstein Meat Grinder turned the area surrounding Shirekeep into a war-torn no-man's land. Faced with increasing instability, the Steward, Thuylemans, urged Kaiseress to evacuate the capital, along with her court, to a safer location. However, the Kaiseress, already physically weakened by a lingering illness and mentally drained by the ongoing crisis, refused to leave Shirekeep. This refusal placed Thuylemans in a difficult position; while he had no desire to govern from a war zone (and certainly not die there), he was left with limited options.

Determined to ensure the continuity of his government, Thuylemans ultimately made the decision to relocate the administration. His official reasoning was that the government should not be cut off from the rest of the Imperial Republic, a sentiment that fueled his desire to move. Although some members of the government favored closer locations like Maltenstein or Fortis, the city of Novi Nigrad on the island of Yardistan was ultimately chosen. This choice was made due to its relative safety, far away from the war, and the fact that the city had been largely pacified in recent years, following the Sathrati Emergency. Additionally, the influx of refugees from Kildari and Benecian Shirerithians had bolstered Novi Nigrad's stability (at least, on the surface).

Thuylemans' decision, however, did not come without resistance. In the Folksraad, many members were opposed to the relocation, seeing it as a retreat. Domitius W. Iritatus, a prominent Shirekeepian politician, even accused the Steward of cowardice. The debate only ended after an hour long rant from the honorable Folksraad member at the adress of the Steward (represented by his poor chauffeur) when a bomb narrowly missed the Palace of Zirandorthel, convincing the Legislature of the necessity of the move. The government leadership's proposal was swiftly agreed upon after this close call.

By mid-1734, as the Benecian offensive intensified with the aim of encircling Shirekeep, the government and parliament evacuated the capital aboard requisitioned airships. Chaos ensued on the airdocks, with locals becoming hysterical after seeing their representatives fleeing. Three politicians were grabbed by a growing mob and torn apart before being incinerated by the heat of the ascending airship. The capital was left in the hands of a skeleton crew of officers, minor bureaucrats, and politicians, with a terminally ill Kaiseress remaining behind at the helm of what was left of Shirekeep's leadership.

This relocation marked a turning point in the Imperial Republic's handling of the conflict, as it moved the center of governance far from the conflict's epicenter to ensure the survival and continuation of the state. he move had been successful and secured the government for the time being, but it dealt a blow to its long-term credibility. Something that would have dire consequences in the long run.

Elections of the Provincial Assemblies of Greater Kildare (late 1734)

By the end of 1734 AN, for the first time in eleven years, the Heavenly Light, the Xinshi Light, called for new elections for the Provincial Assemblies. While disunited and broken up in different Dominions, the former Jingdaoese territories had kept operating more or less with the same political systems and kept cooperating with each other informally. The provincial assemblies, whose composition was still based on the long-outdated elections of the Shirerithian Adelsraad of 1723, had become completely irrelevant. Many of the original representatives had either died, retired, or been replaced by others who had been handpicked by their parties to represent their interests. The political stagnation left the system unresponsive to the rising social and economic challenges.

As hundreds of thousands of young men - both of Kildarian and Jingdaoese descent - were sent to the front lines to fight in the war, the demand for legitimate representation grew louder. Soldiers and civilians alike began to question why they were fighting abroad while socio-economic conditions at home were deteriorating. With increasing food shortages, wage cuts, and oppressive war taxes, the people’s patience was running thin.

The Xinshi Light, renowned for her lack of interest in governance - focusing instead on the more symbolic and social aspects of her role - had largely allowed political decay to take root. Her reputation for easily accepting both the syndicalist regime and the annexation of the Great Jing into Shireroth further eroded her standing among traditionalists and reformers alike. But as pressure mounted due to the war and growing public discontent, even the indifferent Xinshi Light had to act. Reluctantly, she ordered all Provincial Assemblies to be dissolved and, for the first time since the last Imperial Yuan elections of 1657 AN, she called for free elections. While protests erupted among the old political elites, who were unwilling to relinquish their comfortable positions, their opposition remained confined to the backrooms of power, unable to openly challenge the Heavenly Throne amid the ongoing war.

Provincial Elections amidst war

The 1734 AN elections were unique in several ways. Soldiers on the front lines, many of them hardened by the brutality of the war, were granted the right to vote, a move meant to placate the growing unrest within the ranks. However, far from quelling dissent, the elections amplified the divisions within the Greater Kildarian society.

The results were a disaster for the status quo. The long-dominant political parties, such as the Mango-Strengthening Movement and especially the Greater Kildarian Humanists, who had maintained their presence in the Assemblies despite the chaos of war and political crackdowns, were decimated. In their place emerged a lot of independent candidates and a much smaller, but more vocal and extremist faction of monarchists, many of whom called for a constitutional monarchy as a solution to the nation's deepening crisis. These monarchists, though far from unified, generally sought to preserve the Kaiseress' and Heavenly Light's symbolic role while radically reforming the governmental structure to restore stability.

The rise of radicalism

While monarchists dominated the conversation, the elections also gave a platform to more radical elements. A small, but fiery group of republicans began to gain traction, openly calling for the abolition of the monarchy and the establishment of a republican system. Although still in the minority, their presence marked a significant shift in the political landscape. These republicans were particularly popular among the urban working class and disillusioned soldiers who had grown tired of fighting a war they neither understood nor supported. Their call for a people's government resonated deeply with those who felt betrayed by both the old aristocracy and the Heavenly Light’s administration.

The political environment was further destabilized by the growing influence of revolutionary thinkers like Ren Sakuragi, whose message of equality and anti-segregation struck a chord with those tired of the aristocratic privileges and the collusion between the Heavenly Light and the Kaiseress of Shireroth. Ren’s ideas were particularly dangerous for the existing order, as they combined elements of both Jingdaoese and Kildarian dissatisfaction into a cohesive revolutionary vision.

Impending socio-economic collapse

As the war dragged on, the economic situation at home worsened. Food shortages were becoming commonplace in urban centers, while inflation skyrocketed. Corruption and mismanagement within the provincial assemblies made it clear to the people that the old system could no longer provide the stability or prosperity that Greater Kildare - and Jingdao before it - once prided itself on. Simultaneously, the people saw how their Steward, Louis Thuylemans, fled the capital of Shirekeep and exchanged it for Novi Nigrad. The people, exhausted from the war and embittered by the lack of support from the political class, became increasingly radicalized, with many beginning to openly defy their commanders.

The Jingdaoese and Kildarian youth, once patriotic and eager to fight for the nation, now returned home on leave (at least, if they survived the dangerous travel across the Shire Sea, plagued by Benacian attacks) as disillusioned veterans, questioning the legitimacy of the entire political and religious order. The war, which had initially united the people in defense of the empire, had instead become a catalyst for unrest.

The Novi Nigrad Quarrels (1734)

- See also: Novi Nigrad Quarrels.

Reforms and Constitutional Monarchy (1735 - 1737)

1735 Shirerithian general elections

- See also: 1735 Shirerithian general elections

The 1735 Shirerithian General Elections were a defining moment after years of postponed elections. Intended by Thuylemans to quell public unrest and renew political representation, the election instead highlighted the empire’s internal divisions and left Shireroth in greater turmoil.

Despite the ban on political parties, in the Adelsraad (lower nobility) and Folksraad (commoners), factionalism took hold, with five main groups: the Kalirionists (conservative royalists), Aldricists (constitutional monarchists), Mangoists (reactionary traditionalists), Sakuragists (radical reformists), and Verionists (centralist hardliners). The Kalirionists and Aldricists formed a fragile coalition government under Steward Louis Thuylemans, yet reforms aimed at expanding legislative power faced fierce resistance. This political gridlock deepened discontent, with radical groups like the Sakuragists gaining traction and the Verionists denouncing the election altogether.

Mediocre Achievements on the Front

Diverted forces from the Benacian Union to the Batavian front, give the Shirerithians some breathing room. Definitive pushback against the Benacians in Maltenstein region. Succesfull offensive in the Elwynn region (not much land gain, but giving the army a breather and pushes the front farther away from the capital).

Return to the Capital

With the pushback on the Maltenstein Front and some advancements in the surrounding areas of Shirekeep, the government of Thuylemans returns to Shirekeep.

Great Fear and Prison Massacres of 1737

As the government re-established itself in Shirekeep after months of turmoil, whispers of a potential coup d'état began to circulate throughout the capital in early 1737 AN. Fear and uncertainty gripped the city, with both nobles and commoners alike falling victim to the volatile atmosphere. Amid the tension, revolutionary fervor reached a boiling point, and violence erupted on an unprecedented scale. Crowds, incited by rumors of conspiracies and counter-revolutionary plots, turned their wrath towards the prisons and noble estates. Believing these institutions to harbor enemies of the Revolutionary Republic, mobs stormed detention facilities, demanding the immediate execution of prisoners they deemed traitors. Guards and Imperial Marshals, overwhelmed and terrified (or sometimes outright in support of the rioters), often abandoned their posts or capitulated, leaving the inmates at the mercy of the frenzied masses.

The massacres were brutal and indiscriminate. Thousands of inmates—ranging from minor offenders to political prisoners, and including many members of the nobility—were dragged from their cells and summarily executed. Public squares and streets near the prisons became sites of mass executions, with hangings, stabbings, and beatings carried out in plain view. The violence soon spilled over into the noble quarters of Shirekeep, where estates were looted, and families murdered under the pretext of revolutionary justice.

By the end of the year, the city had been scarred by the chaos, with entire districts left in ruin and thousands of lives lost. While peace gradually returned to Shirekeep, it was a fragile and uneasy calm. The radicals, emboldened by the popular uprising, steadily tightened their grip on the government. The Thuylemans government, which had returned to Shirekeep earlier that year, found itself increasingly sidelined as revolutionary fervor consumed the city.

Collapse of the Constitutional Monarchy and Radicalisation (1737 - 1740)

Recession of 1737 and the Fake War

- See also: Recession of 1737, Fake War

To fund its ambitious infrastructure projects before the Shiro-Benacian War, Shireroth had relied heavily on foreign loans, particularly from Nouvelle Alexandrie and Natopia. By 1737 AN, with the national treasury depleted and the economy entirely focused on the war effort, the government declared a unilateral default on its foreign debts. Nouvelle Alexandrie, unwilling to accept this loss, demanded repayment and began preparations for economic and military retaliation.

Ths unwillingness fueled the Recession of 1737, which marked a critical moment in Shireroth's descent into chaos during the Mango Anarchy. The economic turmoil, stemming from years of fiscal mismanagement, war debts, and a failing currency, plunged the nation into crisis. One of the key events precipitating the recession was the Fake War with Nouvelle Alexandrie, triggered by Shireroth's declaration of its unwillingness to repay its substantial pre-war debts.

The "Fake War," as it came to be known, was a brief but symbolic conflict. Nouvelle Alexandrie launched limited military actions, including interdictions on Shirerithian vessels in their territorial waters, to pressure the government into compliance. However, Shireroth, treated the conflict as a sideshow to its internal struggles and the Shiro-Benacian War. The Alexandrian campaign's inability to capture any Shirerithian assets rendered it largely ineffective at achieving its primary goal of debt compensation. It did, however succeeded in making the Shirerithian industrialist elite worried about the inability of their government to repay debts.

Food Riots

National debt, increased demands of the army, a failing currency and trade deficits, combined with farmers unwilling (and hiding) to sell their goods for cheap prices, lead to food shortages and riots. The moderate government loses control.

The economic crisis exacerbated widespread food shortages caused by several factors. Foremost were the trade deficits as a result of years of war. The 1737 Recession had led to a hoarding of foodstuffs by the peasantry and local nobility, fearing that the government or companies affliated to them, would be unable to pay them back. Enforced maximum prices let to an abrupt halt and further (illegal) hoarding and hiding of grain and other goods, especially in Greater Kildare, which saw no direct consequences of the war and had grown into the foodhub of the Imperial Republic.

The Shirerithian currency had lost significant value, rendering imported goods prohibitively expensive. To make matters worse, many citizens were used to strengthen the war effort, which meant that less farmers were available to work the fields they had abandoned. Previous use of nuclear weapons, including during Operation Bad Neighbour II, had also led to environmental damage, reducing agricultural yields in Benacia itself, making the import of food from Batavia and the Eastern Provinces a necessity.

The resulting food shortages triggered widespread riots in urban centers, including Shirekeep, the imperial capital. In many cities, mobs attacked grain depots, government offices, and the homes of wealthy merchants accused of profiteering. The Thuylemans Government, already struggling to maintain order, proved incapable of addressing the crisis.

Revolutionary Committee of Shirekeep (1737)

Amid the chaos, power shifted decisively away from the failing central government to local and radical elements. In Shirekeep, the heart of Shireroth’s political system, the Revolutionary Committee of Shirekeep emerged as a dominant force in 1737 AN.

Formation of the Committee

Under the leadership of Erasmo Laegel, a charismatic radical, the Revolutionary Committee was formed during the height of the food riots. Elected as Prefect of Shirekeep by an ad hoc popular vote of the city's revolutionary mobs, Laegel swiftly moved to consolidate power. Declaring the Thuylemans Government illegitimate, the Committee arrested its ministers on charges of treason and dissolved the central government. Louis Thuylemans himself was locked up in the Tower of the Provost of the Iron Gate, in Raynor's Keep, while awaiting trial.

The Committee was composed of representatives from every bailliwick and city district, ensuring it reflected the diverse voices of the city's population. A new coat of arms, featuring the Tree and Horn of Abundance—symbols of prosperity and equality—replaced the imperial Malarbor emblem. Soldiers, rather than nobles, flanked the new design, symbolizing the revolutionary ethos of the movement.

In a dramatic address to the Legislature's three Chambers, Laegel declared that the Committee would "complete the revolution" by stripping the Mango Throne of its remaining power. While Kaiseress Salome remained a ceremonial figurehead, the Committee effectively transformed Shireroth into a de facto republic, with Laegel acting as the Steward of the new revolutionary government.

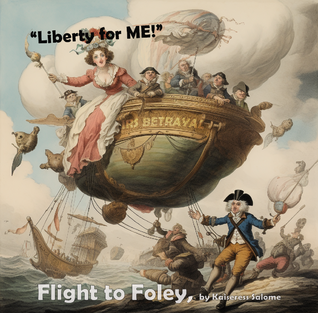

The Flight from Foley (1737)

- IN PROGRESS: Add some peril; make sure the aircraft is tiny and flies low altitude

Kaiseress Salome flees from Shirekeep after her humiliation at the hand of the Revolutionary Committee of Shirekeep. She's helped by loyalists to escape from Foley with an airship. The mission, while initially succesful is betrayed and Salome is kidnapped to Hurmu, where she's locked up by Humanists supports.

- Salome had been under house arrest since her nuclear debacle. With the establishment of the Committee, she de facto becomes a prisoner of the Committee. Her movements are restricted. She still holds a lot of respect among the populace, though.

During the night to 10.XI.1737 Salome attempted to escape the capital with the help of some of her most trusted courtiers. The decision to leave the Keep to escape was controversial. Salome needed to do it clandestinely, as the Benacian Union forces would spare no resources in attempting to apprehend or kill her. After weeks of planning, Salome and her courtiers had made a plan. She would dress as a normal Shirerithian working-class woman, with her small team in similar working-class attire, and then simply drive around in a derelict Faca until they could reach the Foley aerodrome. From there, Salome, a pilot and two bodyguards would take a small electric airplane, fly on low altitude south-westwards across Brookshire until they arrived outside Jakovita. From here, they would take a slightly larger civilian jet (seating 8 passengers) to Kezan via Musica, thus avoiding detection from the Benacian Union forces as well as the knowledge of everyone else of what and whom the plane was carrying.

Despite the clandestine nature of the plan, Yukio found out about it. After working together with those loyal to him in the Shirerithian government and those closest to Salome, he began a collaboration with the Humanist-led Hurmu Fyrð. As such, during Salome's flight across the Straylight Sea, the course was altered. Instead of reaching her intended destination of Kezan, the Kaiseress found herself landing on Hurmu's island of Svetostrov (Holy Island), after having travelled across Senyan airspace (the plane setting up a Hurmu transponder just before entering Senyan space, thus making use of the free-movement clauses of the Xäiville Convention). Upon arrival in Sobor, she was greeted by a welcoming committee consisting of Prince Yukio himself, Viceroy Đorđe Babić, and First Minister Emzsar Kodorishvili.

The political dynamics underlying this operation were complex. Viceroy Babić was known to be an ally of Yukio, while First Minister Kodorishvili maintained loyalty to the Humanist cause and was known of having ties to the Benacian Union. This arrangement reflected a delicate balance of interests between Yukio's ambitions and the Humanists' agenda. The two camps agreed that Salome would eventually have to stand trial for crimes against humanity (i.e., her nuclear attack on the Benacian Union).

Officially, Salome's presence on Svetostrov was framed as her "availing herself of her rights as a princess among the Lakes," with her status ostensibly that of a guest of the Viceroy. In reality, this arrangement amounted to a form of house arrest, severely limiting Salome's movements and influence. A retinue of three scores of equerries from the Hurmu Fyrð, for the Kaiseress's "comfort, ease, and safety" ensured that Salome was never alone and had all her basic needs met.

Yukio's primary objective in this scheme was to pressure Salome into abdicating in his favour, potentially positioning himself as the next ruler of Shireroth. The Humanists, on the other hand, harboured more radical ambitions, hoping to see Shireroth fall under the control of the Benacian Union.

Meanwhile, Hurmu's Senatorial Inquisition began investigating Salome for war crimes, and prosecutors became regular visitors interviewing her.

Failed Jinkeai Expedition

A failed Jinkeai Expedition followed, almost immediately after Salome's Flight from Shirekeep. It was a disastrous monarchist attempt to restore stability and monarchical authority in Shireroth during the Mango Anarchy. Backed by a coalition of exiled aristocrats, Humanists, opportunistic Hurmudan mercenaries, and sympathetic factions within the Jingdaoese population, the expedition sought to rally support for Prince Yukio and end the revolutionary chaos gripping the empire.

In 1737 AN, a force of approximately 12,000 volunteers, including Jingdaoese royalists, mercenaries, and émigré supporters, landed near the town of Xiahu in the Duchy of Jinkeai. The landing was facilitated by bribes paid to local coastal defense commanders, allowing the expedition to disembark unopposed. Among the force was a single, outdated armored tank intended to serve as a morale-boosting symbol of modernity and strength.

The expedition’s objectives were ambitious:

- Rally local Jingdaoese support for Prince Yukio.

- Secure control over the Eastern Imperium.

- March on several northern cities and let the swift victories lead to a revolt against supporters of the republican regime and eventually pressure Daocheng to leave their neutral stance in favour to restore monarchical authority in Shirekeep.

Despite initial successes in securing a foothold, the expedition faltered as it advanced inland. Loyalist Shirerithian troops, organized under the Revolutionary Committee of Shirekeep, intercepted the monarchist force near Sisera Wharf. The Shirerithian military, battle-hardened and well-equipped compared to the motley assembly of the expedition, quickly overwhelmed the monarchist forces.

The outdated armored tank broke down early in the engagement, leaving the expedition without its symbol of strength. By the end of the battle, most of the expeditionary force was either killed, captured, or dispersed. Prince Yukio himself narrowly escaped capture, retreating into exile once more.

The failure of the Jinkeai Expedition was catastrophic for the monarchist cause. It discredited the monarchist factions within Shireroth, demoralized their remaining supporters, and emboldened the radicals in the Legislature. In the aftermath, revolutionary leaders pushed for a harder stance against perceived enemies of the Republic, setting the stage for the Regime of the Bloody Cleansing.

Regime of the Bloody Cleansing (1737 - 1738)

Following the failure of the Jinkeai Expedition, radical factions in the Legislature of Shireroth gained significant momentum. Under the guise of securing the Revolutionary Committee's Republic, they implemented sweeping and often brutal reforms that reshaped Shirerithian society and governance. In 1737 AN, the Folksraad, the populist-dominated chamber of the Legislature, unilaterally absorbed the lawmaking powers of the Landsraad (representing the highest noble houses) and the Adelsraad (with minor aristocratic families). The Folksraad allowed these chambers only a token role through a system of Rogatio, whereby they could propose legislation. However, these proposals were routinely ignored unless they aligned with radical revolutionary ideals.

Key Reforms

The Folksraad, driven by revolutionary zeal, implemented a series of sweeping reforms aimed at reshaping Shirerithian society and consolidating its vision of the Revolutionary Republic. While many of these reforms were well-intentioned, they were often radical in scope and execution. One of the most significant changes was the abolition of class distinctions. The Folksraad declared all citizens equal, erasing the legal and social privileges that had long separated nobles from commoners. This move sought to dismantle the foundations of the old feudal order and affirm the Republic’s commitment to egalitarian principles.

Another major reform was the separation of state and temple, a direct assault on the intertwined power of religious and imperial institutions. State sponsorship of the Temple Cults and Imperial Cult, including those tied to the Kaiseress, was severed. Temples' lands and assets were confiscated, with the proceeds used to fund the Revolutionary government and sustain the war effort. However, this decree had limited reach; in regions like Greater Kildare, the order was ignored or actively resisted, maintaining the temples' influence there.

Perhaps the most dramatic decision was the abolition of the monarchy. The Folksraad formally stripped the throne of its remaining authority, reducing Kaiseress Salome, who was still on the run, to a ceremonial figurehead. Despite this bold declaration, the throne itself was not entirely abolished. The leadership feared that fully dismantling the monarchy would provoke widespread unrest, particularly in the Eastern Provinces, where resistance to the regime remained strong. Many Cedrists, who believed in the divine and celestial nature of the Crown, viewed this reform as a step too far. Finally, the confiscation of noble and temple assets provided much-needed funds for the Republic. Estates and possessions were seized and auctioned off, and the introduction of assignats - a currency backed by these confiscated assets - helped to stabilize the fragile economy, albeit temporarily.

The Bloody Cleansing

To eliminate "internal enemies" and secure its control, the Folksraad launched a brutal campaign of purges and repression known as the Bloody Cleansing. The crackdown targeted the nobility, with remaining aristocrats systematically stripped of their titles. Many were arrested on charges of treason, facing imprisonment or execution. As prisons became overcrowded, forced labor camps were established, where those convicted of counter-revolutionary activities were sent to toil under harsh conditions. Louis Thuylemans was trialed in 1738 AN and forced to fight in the pit till his eventual death. He died at the hand of a woman who had been paid 27 erb and a loaf of bread, without resisting.

Executions became a grim routine, with public hangings, decapitations, and pit fighting on a large scale used both to punish dissenters and to intimidate the population into compliance. To tighten its grip further, the regime created Committees of Public Safety in every major city. These bodies operated as surveillance networks, rooting out counter-revolutionary sentiment and ensuring loyalty to the revolutionary Republic.

This relentless campaign of terror left a legacy of fear and division, solidifying the regime's power at a tremendous human and societal cost. The Regime of the Bloody Cleansing succeeded in consolidating radical control over Shireroth but at an immense cost. The economy, already devastated by war and the Recession of 1737, struggled to recover under the weight of confiscations, forced labor, and social upheaval. The purges created a climate of fear, stifling opposition but also alienating moderates who had initially supported or accepted the revolution.

By 1739 AN, a series of failed harvests and the loss of key territories, such as the Nackholm Pocket, reignited unrest. While the Committee retained significant popular support, divisions between moderates and radicals within the revolutionary movement began to surface, further destabilizing the city and the nation. This left the gates wide open for Prince Yukio, now actively supported by the elite that had been left in Shirekeep, when he launched a new invasion of Jinkeai.

Counter-Coup

Call for Restoration: Yukio's Glorious Return (1740?)

Emigrés in Neighbouring countries

“The nobles who fled do nothing but gorge and feast! They’re rotten to the core. Even our foreign dignitaries have given up on them—they never want to discuss real business, it always circles back to pleading with us to fight their battles!”

- Carlos Méndez, Junior Envoy of the Department of State of Nouvelle Alexandrie.

The émigrés were predominantly wealthy landowners, nobles, and former political elites who fled Shireroth at the onset of revolutionary turmoil, fearing not only the collapse of the old order but also their own safety and property. Many of these nobles had already felt endangered by the 1735 Shirerithian general elections, which brought a constitutional monarchy forward and signaled the erosion of aristocratic privileges. As revolutionary fervor intensified, noble estates and rural fiefs increasingly became targets for peasant uprisings. Villagers who had long endured feudal restrictions took advantage of the political chaos to ransack mansions, seize valuable property, and even burn down estates in acts of symbolic defiance. Local Imperial Marshals and the Armed Forces, tasked with maintaining order, were often overwhelmed or simply unmotivated to protect the nobility.

By 1737 AN, radicals had seized control of the Folksraad and Adelsraad, sidelining the Landsraad and solidifying their influence over the government. With the Legislature under radical rule, further persecution of the nobility ensued. Emigration became forbidden, but through connections, many émigrés managed to slip out of Shireroth, making their way to neighboring states. Senya, Hurmu, Natopia, and Nouvelle Alexandrie saw a sudden influx of Shirerithian nobles seeking refuge. Although some of these nations harbored sympathies for the dispossessed nobles, others, such as republican Sanama, were less enthusiastic about offering asylum to aristocrats whose privileges were antithetical to republican ideals.

Once abroad, many émigrés found themselves in precarious positions. They often expected support from their hosts, hoping to form a coalition for an anti-revolutionary incursion to reclaim Shireroth. However, the political climate was unfavorable for such ventures. With memories of the 1737 recession still fresh and a financial crisis brewing due to Shireroth’s debt default, few countries were willing to fund an intervention against the radical government in Shirekeep, especially as doing so risked drawing retaliation from Shireroth’s Imperial Navy.

Ultimately, the émigrés’ dream of a restoration movement floundered, leaving them isolated, often resented, and dependent on their host nations’ goodwill. Their presence would continue to fuel political and diplomatic tensions across Micras, as each host nation had to navigate between the demands of their Shirerithian guests and the risk of antagonizing the volatile revolutionary government in Shireroth. Especially Hurmu, which was hosting Prince Yukio, who launched a failed military expedition in 1737 into Jinkeai, had trouble navigating between neutrality and war.

Timeline

See also

- Shiro-Benacian War

- Recession of 1737

- Fake War with Nouvelle Alexandrie and Natopia

- The Great Goat Heist Incident, border skirmish between Shireroth and Senya.

- Shirerithian emigration to Nouvelle Alexandrie