Normandie: Difference between revisions

| Line 176: | Line 176: | ||

In mid-{{AN|1750}}, the Báthorians left Normandie to establish their own nation. The vacated Arpad region attracted a large number of Normandic refugees due to its warm soil and was densely populated. | In mid-{{AN|1750}}, the Báthorians left Normandie to establish their own nation. The vacated Arpad region attracted a large number of Normandic refugees due to its warm soil and was densely populated. | ||

In I.II.{{AN|1751}}, [[Fatima of Arbor]] was cleared of all her crimes by Theodoric van Orton. Finally, Fatima of Arbor (formerly Lady Esther) regained her former honorary title after a long time. Later, a bust of Esther was added to the monument to the [[Heroes of Normandy]] in Quimper. | In I.II.{{AN|1751}}, [[Fatima of Arbor]] was cleared of all her crimes by Theodoric van Orton. Finally, Fatima of Arbor (formerly Lady Esther) regained her former honorary title after a long time. Later, a bust of Esther was added to the monument to the [[Heroes of Normandy Park]] in Quimper. | ||

==Government and poltics== | ==Government and poltics== | ||

Revision as of 11:12, 4 December 2025

| L'Ordre des Lacs sacrés du chef du duché de Normandie The Order of the Holy Lakes in right of the Duchy of Normandie | |||

| |||

| Motto: Li rosignol as roses | |||

| Anthem: | |||

| |||

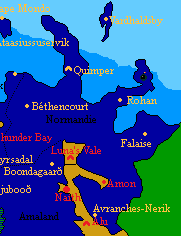

| Map versions | |||

| Capital | Quimper | ||

| Official language(s) | Normandic, Hurmu Norse | ||

| Official religion(s) | Norman Luminist Church | ||

| Demonym | Normandic | ||

| - Adjective | Normandic | ||

| Government | realm of the Order of the Holy Lakes | ||

| - Duke | Theodoric van Orton | ||

| - Legislature | |||

| Establishment | 1744 AN | ||

| Area | 909,111 km2 | ||

| Population | 13,868,371 (1750) | ||

| Currency | Crown (HUK) | ||

| Calendar | |||

| Time zone(s) | CMT+3 | ||

| Mains electricity | |||

| Driving side | left | ||

| Track gauge | |||

| National website | |||

| National forum | |||

| National animal | Lion | ||

| National food | |||

| National drink | Grape ale | ||

| National tree | Willow | ||

| Abbreviation | TBD | ||

Normandie (also spelt Normandy; in Hurmu Norse: Noorðmannaland; see also that article) is one of the List of realms of the Order of the Holy Lakes of the Order of the Holy Lakes located on the west coast of Keltia, in the Normandie region, immediately north of Amaland and east of the Hexarchy. Normandie was admitted to the Order of the Holy Lakes on 6.I.1745.

Known for its rugged terrain, long, harsh winters, and historically rich settlements and culture, Normandy traces its origins to the era of the Leopard Brothers. Wars with the kingdoms of Franciana and Bosworth contributed significantly to the development of Norman history. The invasions of Varja, Durnktistan, Karnali, and Korhal brought about a period of Norman rule. The subsequent Storish rule profoundly undermined the region's cult and independence. Until 1685, it was ruled by the iron fist of Harald and Fatima of Arbor. The church's structure suffered significant deterioration during this period of despotism.

After the fall of Stormark in 1685 AN, the region was divided among various knights and warlords. Later, during Lysstyrer's reign, the Normans left the region and dispersed elsewhere. After Lysstyrer, the Normans began to settle again.

Years later, the Normandid Revolt Army emerged in Normandie, now a forgotten region. In 1744 AN, Normandy was refounded by Theodoric van Orton. Today, the duchy aims to maintain religious purity, completely erase the Vanic past, and embrace stateless people.

With a population of nearly 15 million, the duchy's economy is dependent on livestock farming, sustainable agricultural production, the service sector, tourism, and industry. While influenced by Alexandrian cultural influences, the Norman people still retain some of their Norse heritage. The Normans were indirectly influenced by the Celtic Kernevons, the Greco-Romans (Sicilian era), and the Anglo-Saxons (Bosworth). Normandy continues to be a region of occasional unrest and unrest.

Profile

Present-day Normandie is a significant region with a long history. Normandie is a realm known for its chivalry, heraldic culture, feudalism, and historical service to the Nazarene religion. The Duchy of Normandie, the former Storish Jarldom, was a vast territory, encompassing cold, icy seas and warm, fertile coasts, mountainous terrain and flat plains. After the collapse of Stormark in 1685 AN, Normandie shrank considerably. Normandie, now dominant only in the north of the former lands, has managed to preserve most of its non-heretical ideas. However, the former Normandie lands are known geographically as Noordmannaland, and several realms claim this legacy.

Normandie is located on the western fringe of the Twin Peninsula, facing the Sunset Sea to the west. The landscape consists of fertile plains, low mountainous ridges to the east and south, broad river valleys, and temperate forests. Historically rich in game and natural resources, the region has sustained agricultural and pastoral communities for centuries. Once a core province of Stormark, Normandie played a central role in preserving and promoting chivalric traditions. Together with Port Chloe and the Providence Plantations, it formed the heartland of knightly culture within the High Realm. Formal tournaments, hereditary orders, and codes of knighthood were more strictly observed here than anywhere else in the former realm.

After the fall of Stormark (mid-1685 AN), the Duchy of Normandy ceased to exist. Normandy was divided among various warlords. The region, which had descended into a post-apocalyptic scenario, also posed significant problems for its citizens. In the chaos, half the population either fled to the green, sought refuge in Hurmu's Amaland and Karmanark regions (this would happen in later years), or perished. In 1686 AN, the Hexarchy invaded the region and established the autonomous region of Lysttyrer. Border conflicts also existed between Hurmu and the Vanic remnants until 1729 AN. Most settlements within the former Duchy of Normandy fell into the hands of various nations. The Hexarchy then disappeared in 1736 AN, and much of the land within the Lysttyrer autonomous region, which had been under the Hexarchy's control, was reduced to green land. Neo-Vanic militants had been trapped in the Falaise region since 1686 AN. The evolving circumstances allowed them to become well-armed and spread throughout the region. Sensing the danger of the region, Theodoric van Orton revived the Norman movement to find new adventures and by 1743 AN had gained complete control of the rural areas of Ortonia and the core of the cities.

On New Year's Day 1744 AN, the Duchy of Normandy was reestablished after a fifty-nine-year hiatus. Theodoric van Orton transformed Normandie into an elective monarchy and, rather strangely, linked the elections to professional wrestling tournaments. This concept has no previous precedent in Micras. The paramilitary Norman Revolt Army expanded into even Green territory. Normandie was admitted to Hurmu in 1745 AN, and Theodoric van Orton's office was formalized. Normandie's claim map expanded and was accepted by the MCS. Later, the NRA became the Normandokarum Fyrd. However, in the same year, Normandie's status was threatened but was saved by the resistance. Between 1746 AN and 1747 AN, the war's impact diminished to almost zero, and economic investment in Normandie accelerated, particularly in industry. In 1747 AN, Theodoric van Orton was knighted by the Order of the Holy Lakes for his fight against the Vanic horde and for his work on the Brida values. In 1748 AN, Karum was incorporated into Normandie.

However, Normandie's return was not entirely flawless. The former duchy's important cities and most of its territory were lost. Knightly and ecclesiastical culture was severely damaged. This was addressed through the spread of Luminism. The army was modernized and reduced to just five regiments. The purple-and-yellow color combination was changed to red-and-yellow, likely as a tribute to Franciana. All Vanic materials deemed dangerous by the Ministry of Social Control were completely destroyed. Nor was there any trace of Normandie's former prosperity. Generally, Noordmannaland remained deprived of significant investment and became increasingly impoverished. Normandie's circumstances were different, with regional chaos significantly eroding the wealth of the northern lands.

Today, in Normandie, rapid population growth in the capital, Quimper, slums, infrastructural deficiencies in the suburbs, and disorganization are severely damaging the city's historical image. Furthermore, ethnic discontent, general lack of services, human rights violations, restrictions on private business, arbitrary arrests, Vanic panic, harsh climate conditions, and nepotism are widespread. Per capita income in Normandy ranges between 380 and 400 crowns, making it one of the poorest realms among the Hurmu realms. Despite all this, the growth of the automotive sector and the abundant cheap labor force offer hope to the region. Livestock farming continues to be the main source of income in rural areas, while the service sector is prevalent in the metropolitan areas. The annexation of Karum has provided access to warmer lands and also facilitated access to agriculture. Despite this, Normandy continues to experience a brain drain, and significant investments are being made in the education sector to address this.

History

Norse Roots and Francian Domination (c. 500–1040)

The origins of Normandie lie in the early Norse settlements that began in the sixth century AN. These settlers established their culture and language across the region, with Old Norse becoming dominant among the common population. In the early 900s, the Kingdom of Franciana, an Old Alexandrian-speaking realm, conquered the territory. Although Francianan rule began the slow Alexandrianization of the region, linguistic and cultural assimilation remained limited. The nobility gradually adopted Alexandrian, while the common folk retained their Norse identity.

The War of the Hand of Hallvarður (1103–1108) and the County of Quercy (1108–1150)

The saga of Normandie's true founding begins with the birth of Rognvald of Valtia in 1040, father of the twins Horik and Hyngwar Rognvaldsson, who were born in 1078. Following their father's assassination in 1100, widely believed to involve the Valtian leadership, the twin brothers were eventually exiled from Valtia. Their notoriety as brutal, cunning mercenaries—commanders of the feared Leopard Legion—preceded them.

In 1103, the Valtian Althing dispatched Jarl Hallvarður Jónsson of the House of Haukdælir to negotiate a political alliance with Franciana, including a proposal for the marriage of Princess Clotilde to a Valtian noble. Rather than accept the offer, King Clovis responded with cruelty and contempt. He had Hallvarður's hands severed and returned them to Valtia with a mocking note. The mutilated envoy was then stoned to death, and his remains desecrated.

This act constituted not merely an insult but an act of war under the diplomatic customs of the time. It was a sacrilegious breach of the sacred trust afforded to emissaries, universally acknowledged as inviolable. The Althing of Valtia declared war, calling upon their maritime chieftains, privateers, and allied warlords to exact retribution.

Valtian-backed corsairs and mercenaries descended upon Franciana, devastating its coastal settlements and trade. Neighboring powers, including Vermandois and Noyon, took advantage of the chaos to launch their own incursions. Franciana, already strained by internal disunity, found itself under siege on all fronts. In desperation, King Clovis turned to a pair of exiled Valtian mercenaries: the Leopard Brothers, Horik and Hyngwar Rognvaldsson.

These brothers—known for their brutality and martial brilliance—had personal grievances against Valtia. In 1104, they agreed to enter Clovis's service. Their Leopard Legion turned the tide of war. At the Battle of Narresroux, they crushed the forces of Vermandois, restoring Franciana’s strategic footing. They were instrumental in purging the land of raiders and bandit hosts.

With Franciana under siege by pirates, mercenaries, and rival kingdoms, Clovis sought unlikely salvation in the Leopard Brothers, who had no allegiance to Valtia and had already begun opportunistic raids in the region. In 1104, the brothers entered Clovis’s service and were rewarded in 1108 with the County of Quercy under the Treaty of Pont l'Évêque. This feudal investiture, marked by the symbolic banner Montjoie, is regarded as the birth of the Duchy of Normandie.

Early Duchy of Normandie (1150–1350)

Horik's son Rollo was born in 1109 and later inherited the county in 1144 following the deaths of Horik (1134) and Hyngwar (1144). Intermarriages with Franciana’s nobility laid the dynastic foundations of the Norman nobility, while the Leopard Brothers' consolidation of power ushered in feudal order. In 1150, Rollo declared himself Duke of Normandie and his duchy independent of Franciana.

With Rollo's succession and stabilization of rule, Normandie grew steadily in influence. The apex of this ascent came with Duke Fulk, the grandson of Rollo, who in 1204 famously conquered the kingdoms of Bosworth and Anglethyr. His rule extended Norman reach across Micras and reinforced their reputation for martial supremacy and cultural sophistication.

Following Fulk's death in 1228, Normandie entered a century-long period of chivalric golden age (1250–1350), defined by the flourishing of knighthood, heraldry, and troubadour culture. The Norman Code of Chivalry, an intricate synthesis of martial, religious, and romantic ideals, was codified and celebrated in tournaments and courtly life.

Fragmentation and Foreign Rule (1350–1543)

Following the end of its golden age, Normandie was increasingly entangled in external conflicts and political instability. From 1452, it was incorporated into the Free Republic and then successively occupied by Varja (1470–1483), Korhal (1487–1490), and Karnali (1490–1516). Governance was inconsistent, and by 1516, Normandie was once again leaderless. Incursions by Durntkinstan beginning in 1529 and expanding in 1534 in the north, and Iridia (1544), in the south, fragmented control.

This was a period of significant decay in Norman sovereignty. The nobility lost cohesion, and ecclesiastical leadership became increasingly influenced by foreign ideologies. It set the stage for a desperate population to welcome Stormark as liberators.

Vanic Subjugation and Cultural Corruption (1543–1685)

In 1543, Stormark entered the scene under the guise of liberators but quickly imposed their ideological and cultural hegemony. Harald Freyjugjöf the Generous Giver, High King of Stormark, was installed as Duke of Normandie. Under Stormark's influence, the Duchy entered an era of Vanicization that deeply corrupted its institutions.

The Église de Normandie, once a Nazarene church rooted in feudal piety, was transformed into a libertine vessel of Vanic cultic influence. The worship of Vanic deities as saints, the installation of female clergy in parity, and ritual nudity during liturgy marked the church's decline into hedonistic spectacle. Most troubling was its theology of sexuality, which elevated polyamory, self-gratification, and public eroticism as sacred acts. Though couched in the language of love and freedom, these practices constituted a profound betrayal of the values upon which the Duchy was founded.

While Stormark praised this era as one of cultural flowering, Norman traditionalists regarded it as a time of humiliation and degradation. The once-honoured Norman Code of Chivalry was distorted into a parody of itself, entangled with Vanic rites and arcane symbolism. Harald Freyjugjöf ruled as both Duke and Pontiff, despite not adhering to the doctrines of the very church he led – a glaring contradiction.

Collapse and the End of Ducal Normandie (1685)

Stormark's collapse in 1685 marked the abrupt end of the Duchy of Normandie as a coherent political and religious entity. No successor government emerged with legitimacy or stability. The Église de Normandie fragmented into regional sects, all repudiating their Vanic past and returning to more orthodox Nazarene traditions. But the damage was lasting: centuries of feudal heritage and chivalric tradition lay buried beneath the rubble of spiritual libertinism and foreign occupation.

Normandie in the Green

- Add context with Amaland and Karnamark... Vanic warfare in the Green

In the late 17th century, during a period of regional instability, Hexarchy forces invaded and annexed the territory. This marked the beginning of a turbulent era. Control was later transferred to the Autonomous Region of Lysstyrer, under which the Normans experienced partial self-governance but limited cultural freedom.

A darker chapter began with the emergence of the Vanic bands, lawless raiding parties whose reign of terror disrupted daily life and eroded local autonomy. For years, these groups committed acts of violence, religious desecration, and economic sabotage across Normandie.

Re-establishment of the Duchy in Ortonia

In 1744 AN, after a sustained campaign of resistance and a series of decisive skirmishes, the Vanic presence was entirely eradicated in Ortonia. This victory is annually commemorated as the Day of Purification, marking a turning point in the duchy’s modern history and solidifying its commitment to self-determination and spiritual unity. In 1745 AN, Normandie was admitted to the Order of the Holy Lakes as a realm. The borders of the duchy were extended by Act of Senate later the same year.

Purification ov Normandie

The Quimper–Béthencourt Offensive, part of the Normandie Revolt in 1744 AN, was a military campaign by the Normandie Revolt Army (NRA) aimed at expelling the Keltia Restoration Movement (KRM) from the western provinces of Normandie.

The KRM, a radical paramilitary group, had entrenched itself in Quimper and Béthencourt, creating unrest in the region. The NRA, led by Theodoric van Orton, launched a coordinated offensive, codenamed Operation Fenrir Eclipse, to reclaim these territories.

The assault on the outskirts of Quimper began on 2 June 1744 AN. Mechanized divisions, drones, armed drones, and artillery were deployed to neutralize the KRM defenses. By 10 June, NRA forces declared the city secure, but more than 40,000 civilians fled during the fighting, many of whom suffered very serious injuries.

Urban combat in some of Béthencourt's outlying areas continued from mid-June to the end of September. The KRM used underground tunnels (mainly sewers), rudimentary booby traps, and guerrilla tactics, while the NRA deployed special mercenary brigades and air support to wage underground warfare. Civilian casualties mounted, leading to martial law throughout the city and forced evacuations to nearby villages. By the war's conclusion, the NRA controlled the entire border of the present-day Lordship of Béthencourt. Following the Béthencourt Offensive, the KRM was unable to re-enter the area.

By September 27, the NRA had virtually complete control of both provinces. The KRM leadership had eliminated all Vanatru elements present in the region, including the KRM resistance in Lunhavre and Hivernot. Remaining KRM forces were dispersed into rural guerrilla cells in Nouveau Bajoccas and Kernevona, because KRM no longer capable of conducting conventional operations. However, the KRM would later return to the region...

The NRA, urban on the confidence of previous offensives, launched an offensive on Rohan in October. The Rohan Offensive, which began on October 5th, saw the NRA achieve its first rapid victory when it occupied Nouveau Bajoccas. Nouveau Bajoccas was captured after a low-scale urban assault and a naval blockade. On October 15th, the NRA advanced into the city of Rohan, but suffered only minor losses thanks to the KRM's barricades and trench network, resulting in a defeat.

The NRA directed its mechanized infantry and mercenaries towards Falaise. Halfway through the Falaise Offensive, which began on November 23rd, the KRM was subjected to guerrilla raids, disrupting its logistics and supply network. With its logistics network severed, the NRA infantry was forced to retreat near Grisboeuf in January 1745 AN The war would culminate in a year of continuous KRM advances.

Both of these defeats highlighted the NRA's lack of equipment for its first two counterattacks and weakened NRA morale. People in the captured territories lost confidence in the organization. Meanwhile, both of these KRM successes later led to the KRM's advance to Quimper. Meanwhile, pressure continued from Kernevonia.

The Siege of Quimper (May 25 – August 30, 1745) was a major turning point in the Purification ov Normandie. The Neo-Vanicist extremists of East and North Normandie (EANN) attempted to capture Quimper, the capital of Ortonist Normandie. The battle followed the Nouveau Bajoccas and Beurville Offensives. On May 25, the EANN began to advance into the outskirts of the city.

After significant gains by the EANN, including control of half the city, the offensive became a stalemate. Vanic leader Hælæif Kaupmannsson was killed in late July during a failed counter-attack on the city center. Operation Silver Root, a counter-attack launched by the Normandokarum Fyrd, forced the besiegers to retreat on August 30. August 30 is celebrated annually in Normandy as Day of the Resistance.

The Liberation of Arpad (late 1745) was an operation conducted by the Normandokarum Fyrd and the Nordstorm Division across the western territories of eastern and northern Normandy. After a short but arduous campaign in the mountainous and cold terrain, loyalist forces easily overran lordship's capital Nors and killed one of the EANN commanders, Runolf Svansson, in a hail of bullets. His death signaled the collapse of Vanik influence, first within the Arpad Lordship and later more generally.

Following the liberation of Arpad, the Normandokarum Fyrd launched an attack on Kernevonia to eliminate the EANN elements threatening it in the north. The harsh winter weather favored the Fyrd, who drew abundant resources from the Hurmu center. Furthermore, the Kernevonian Resistance Volunteers played a significant role in the Kernevonian Campaign. KRV volunteer units captured Casse-glace (Nantes in Kernevon) on January 4 1746. By January 16, all of Kernevonia was liberated from the Vanic threat.

The Hivernot and Lunhavre campaigns, which ran concurrently with the Kernevonia campaign, were successfully concluded on the same day the war began. The recapture of Nouveau Bajoccas, which opened the door to the Rohan Offensive, was concluded on February 24. The collapse of EANN was rapidly progressing...

Having suffered considerably during the winter, the Fyrd and its coalition forces assumed defensive positions to rest in the spring. They continued to grapple with internal problems with the EANN on the other side. On April 18, they launched a bombing campaign against the Rohan bypass roads supplying the EANN. Following a prolonged blockade, the Fyrd began advancing on Rohan on May 23. Resistance in Rohan proved less than expected, resulting in a Fyrd victory on May 30. Rohan fell after a brief siege and the suicide of General Dunfjall Blængsson. Blaengsson's loss severely demoralized the EANN resistance and led to its rapid disintegration.

The campaign secured the north, broke key Vanic communication lines, and is remembered as a turning point marking the decline of organized Vanic resistance in Normandie.

The capture of Falaise (June 22 – October 25, 1746) was the final phase of the Eastern campaign. Fierce street fighting allowed the Normandokarum Fyrd to advance block by block through tunnels and industrial ruins. The death of the senior Vanic general Värmod Gudbrandsson while fighting in a silo severely demoralized the defenders and led to the fall of the city, effectively bringing the entire eastern corridor under coalition control. This victory paved the way for offensives at Grisboeuf and Grenoble later that year and is crowned by the Falaise Victory Column, which symbolizes the collapse of organized Vanic resistance in Normandy.

In early 1747 AN, the Normandokarum Fyrd launched Operation Cold Maw against the prison settlement at Vardhaldsby, the pro-Vanic city on Old Gaol Isle. Three days of intense air and naval bombardment destroyed most of the key weapons installations and prison clusters, freeing Ortonist prisoners and descendants of anti-tyranny and Henryite prisoners. The attack brought a brief but effective end to the terror tension in the permafrost. Following the destruction, the EANN was forced to negotiate with the Ortonists. With the Ashen Accords, the EANN ceased fighting and symbolically burned their weapons. Svafar Kveldulfsson left Normandy, with gendarmes in control of the country. After the Ashen Accords, tensions in the country eased considerably. However, occasional small-scale, independent terrorist attacks continued.

Events outside Purification ov Normandie

Economic investment in Normandy began after the signing of the Treaty of Ashen in 1747. The first five-year plan began in 1746 and became the basis for building the industrial sector.

On 15.X.1746, the Senate of the Lakes inducted Theodoric van Orton into the Order of the Holy Lakes as a Knight of the Holy Lakes, for his work in pacifying Normandie and promoting the values of the Brida there.

The 1746 AN Falaise and Rohan Pogroms were two weeks of violence, looting, and forced displacement in Normandy from November 10–24, 1746 AN. The target population were Heartlanders, migrants from the Heartland, the central region of the Storish lands. The pogroms were motivated by allegations that this population collaborated with the East and North Normandy (EANN).

The presence of the Heartlanders greatly unsettled the Normans, who viewed them as a potential source of financing for further terrorist attacks. The pogroms lasted two weeks. Houses and businesses marked with inverted crosses were set on fire during the pogrom, which centered around Rohan and Falaise. Security forces were very slow to intervene due to the ongoing war.

Numerous assaults, lynchings, and looting were reported during the pogrom. The report added that some special legions participated in the pogroms. Theodoric van Orton proposed that all mainland Heartlanders be "sent" to Old Gaol Isle. The pogrom was suppressed, albeit with difficulty.

Family contact was established with Sanpantul in 1747 AN. In return for the Normans' protection of Sanpanese interests, Sanpantul transferred the factories and headquarters of some of its firms to Normandie.

In 1748 AN, a herd of twenty thousand Reindeer Herder refugees was admitted from the Normandy Buffer Zone. The Reindeer Herder refugees were persecuted by the Confederacy of the Dispossessed in Normark. The refugees were settled in the lordships of Casse-glace and Vardhaldsby.

In X.IV.1748 AN, Karum was annexed to Normandy. The autonomy of the Twelve Pirs and the Allist people in Karum was preserved. Avranches, the ancient and now abandoned ghost town, and Nerik, the heart of Karum, have started receiving infrastructure investments again.

In 1750 AN, Bassaridia Vaeringheim forces advanced further into and annexed former Normark territory. This resulting in more Reindeer Herder, Bosworthians, and Norse refugees arriving in Normandy. The approximate number was thirty thousand.

In I.VII.1750 AN The flag of Normandie has changed for the second time. The royal purple of the former Normandie Jarldom has been added to the flag.

In mid-1750 AN, the Báthorians left Normandie to establish their own nation. The vacated Arpad region attracted a large number of Normandic refugees due to its warm soil and was densely populated.

In I.II.1751 AN, Fatima of Arbor was cleared of all her crimes by Theodoric van Orton. Finally, Fatima of Arbor (formerly Lady Esther) regained her former honorary title after a long time. Later, a bust of Esther was added to the monument to the Heroes of Normandy Park in Quimper.

Government and poltics

Today, the Duchy of Normandy is governed as a duchy, a realm of the Order of the Holy Lakes. Since 1744 AN, the government has been an elective monarchy. However, the monarchs' term of office is generally governed by the Norman Wrestling Company. Pro-wrestling is considered the cultural symbol of Normandy.

Religion and state are not strictly separated. The Norman administration derives its power from the Norman Luminist Church, a reformed version of the Église de Normandie. Under Normandy, all heretical beliefs dating back to the Vanic period are prohibited and taboo. The Luminists combine ancient medieval Norman traditions with the Nazarene, ensuring a unified understanding of both customs and religion. But ultimately, because it is a reformist church, it approaches society more humanely.

The governmental structure is hierarchical but participatory; it includes lordships, county councils, district councils, and villages, all of which are governed by wrestlers from the NWC. Although the lordships have a federal understanding, they are ultimately under the command of Normandie.

List of rulers

For a family tree of the pre-Storish rulers, see Rognvald of Valtia.

| Name | Birth | Title | Tenure | Death | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horik Rognvaldsson | 1078 | Count of Quercy | 1108–1134 | 1134 | Twin brother of Hyngwar |

| Hyngwar Rognvaldsson | 1078 | Count of Quercy | 1108–1144 | 1144 | Twin brother of Horik |

| Rollo le Léopard | 1109 | Count of Quercy | 1144–1150 | 1192 | Son of Horik, nephew of Hyngwar; Elevated to Duke after unifying Norman holdings |

| Duke of Normandie | 1150–1192 | ||||

| Fulk | 1152 | Duke of Normandie | 1192–1228 | 1228 | Son of Vilhelm, son of Rollo. Vilhelm predeceased his father. |

| Osmond le Juste | 1185 | Duke of Normandie | 1228–1247 | 1247 | Eldest son of Duke Fulk; known for legal reform and stabilizing chivalric orders. |

| Raoul de Quercy | 1210 | Duke of Normandie | 1247–1269 | 1269 | Son of Osmond; consolidated Norman control over Bosworth. |

| Bertrand I | 1235 | Duke of Normandie | 1269–1293 | 1293 | Nephew of Raoul; claimed ducal title through maternal line and papal support. |

| Arnaut I | 1268 | Duke of Normandie | 1293–1294 | 1294 | Young son of Bertrand I; ruled briefly before dying of illness. |

| Bertrand II | 1242 | Duke of Normandie | 1294–1302 | 1302 | Uncle of Arnaut I; reclaimed title amidst regency collapse. |

| Henri de Béthencourt | 1270 | Duke of Normandie | 1302–1348 | 1348 | Married Bertrand II's granddaughter; brought Béthencourt line into succession. |

| Louis the Protector | 1312 | Duke of Normandie | 1348–1366 | 1366 | Son of Henri; emphasized religious patronage and cathedral expansion. Considered a patron saint of the Norman church, with the epithet, "the protector" (Le Protecteur). |

| Amaury I | 1338 | Duke of Normandie | 1366–1380 | 1380 | Cousin of Louis; succeeded by designation during Louis’s final illness. |

| Gilles | 1359 | Duke of Normandie | 1380–1387 | 1387 | Son of Amaury I; died young in a hunting accident. |

| Thibault | 1326 | Duke of Normandie | 1387–1423 | 1423 | Elder cousin of Gilles; brought stability during times of external threat. |

| Arnaut II | 1400 | Duke of Normandie | 1423–1429 | 1429 | Grandson of Thibault; killed in battle against Varjan forces. |

| Bertrand III | 1403 | Duke of Normandie | 1429–1433 | 1435 | brother of Arnaut II; abdicated due to illness. |

| Henri II | 1408 | Duke of Normandie | 1433–1449 | 1449 | youngest brother of Arnaut and Bertrand; last fully autonomous duke before period of instability. |

| Amaury II | 1430 | Duke of Normandie | 1449–1450 | 1450 | son of Henri II; killed in uprising. |

| Geoffroi the Short-Reigned | 1425 | Duke of Normandie | 1450–1450 | 1450 | Cousin of Amaury II; reigned only six months; son of Jeanne d'Autuncourt – the sister of dukes Arnaut II, Bertrand III and Henri II. |

| Jeanne d'Autuncourt | 1405 | Duchess of Normandie | 1450–1452 | 1470 | Sister of Henri II, Bertrand III, and Arnaut II, mother of Geoffroi; Ruled as duchess before Varjan occupation began. She was also the only female duchess in her own right of Normandie, as all other male descendants were dead at this point. |

| – | – | – | 1452–1543 | – | Interducal era due to warlordism, foreign occupation, and the collapse of internal succession. |

| Harald of Stormark | 1446 | Duke of Normandie | 1543–1685 | 1685 | Duchy of Normandie (Stormark) |

| Esther | 1638 | Imperial Chieftainness of Normandie | 1638–1685 | 1703 | Paternal great grandchild of Harald; title given by Harald at her birth; mainly symbolic. She renounced the title in 1685. |

| – | – | – | 1685–1744 | – | Interducal era due to warlordism, foreign occupation, etc |

| Theodoric van Orton | 1701 | Duke of Normandie | 1744– |

Demographics

| Municipality | Population | Norman | Kernevon | Austrmarker | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quimper | 4,103,472 | 65% | 20% | 5% | 10% |

| Bethencourt | 2,100,234 | 80% | 1% | 5% | 14% |

| Casse-glace | 318,323 | 18% | 70% | 2% | 10% |

| Old Gaol Isle | 11,172 | 5% | - | 95% | - |

| Falaise | 960,322 | 35% | 2% | 50% | 8% |

| Rohan | 801,345 | 45% | 3% | 45% | 2% |

| Grenoble | 315,387 | 70% | 1% | 19% | 20% |

| Arpad | 471,324 | 98% | - | - | 2% |

| Hivernot | 841,324 | 52% | 41% | 2% | 5% |

| Lunhavre | 600,380 | 85% | 1% | 12% | 2% |

| Nouvelle Bajoccas | 676,342 | 90% | 1% | 8% | 1% |

| Grisboeuf | 356,020 | 90% | - | 2% | 8% |

| Beurville | 406,234 | 99% | - | 1% | 6% |

| Karum | 120,435 | 6% | - | - | 94% |

| Vermandois | 269,325 | 91% | - | 2% | 7% |

| Franciana | 326,432 | 90% | - | - | 10% |

| Refugees in satellite camps | 1,190,300 | 85% | - | 15% |

The vast majority of the Norman population consists of Normans. Their lineage traces back to the Valtian Vikings, and the Leopard Brothers, who founded Normandie, originated from them. Following the invasion of Francia in the 9th century, the city came under the influence of Alexandrian culture, but the people retained Norse influence. By the 17th century, their culture had become influenced by Alexandrian culture, which had a strong Norse influence.

Throughout history, the Normans have been known for their Romanesque architecture, their code of chivalry and virtue, and their strong warrior-like character. Their success over various empires led to the Normans absorbing influence from other cultures. Later, the Normans were invaded by foreign powers. However, the Storish yoke, which began in the 16th century, led to the social decay and corruption of the Normans. The deterioration of the Église de Normandie naturally led to great devastation in Norman society. Harald ruled Normandie for a long time. When the Storish influence finally ended in 1685, the Normans dispersed to Keltia and eventually conquered the southern parts of Amaland and Karnamark. The main part remained in Lysstyrer. As Lysstyrer shrank, the Normans began to return to the region. The Normans finally re-established Normandie in 1744 under the rule of the great leader Theodoric van Orton.

The Kernevons are the second largest ethnic group. In the 4th century, they separated from the Celtic tribes and settled in northern Normandy, in northern Celtic. The Principality of Kernevonia, which existed until the 9th century, came under the rule of Franciana and then under the Normans. During the Norman period, the autonomous counties of Kernevon existed. Although ethnic Alexandrianization occurred, the cultural and linguistic structure was preserved. The remaining relations with the Bosworth kingdoms sustained the culture. The Kernevons came under Middle-earth fantasy, communism, and Anglo-Saxon influence, and in 1470 AN they founded Varja. In 1484 AN, Varja was destroyed, and Kernevons fell back under some Norman influence. During the subsequent Storish rule, they became almost invisible in society and became heavily Alexandrian. From 1685 AN onward, Kernevon culture experienced a revival. Kernevons lived primarily on the Saxon Peninsula, with large concentrations in Casse-glace, Lunhavre, Quimper, and Hivernot. Kernevonians occasionally sought autonomy over Kernevonia. Kernevonians were heavily socially marginalized by the Normans, but under the Ortonist Doctorine, their culture was allowed to survive. By 1750 Kernevons had fallen from second to third place.

Heartlanders are the third largest ethnic group. A small portion of the Heartlanders arrived in Normandie from the Heartland Jarldom in the late 15th century. Trade flourished in Normandie, and they began acquiring their own land and establishing their own villages. Heartlanders also significantly disrupted the cultural fabric of the Église de Normandie, a fact that remains true even if the historical record is objective. After the fall of Stormark, the Heartlanders dispersed throughout the region, experiencing a significant population decline. Later, Catholic feudal lords in the region's green lands converted the Heartlanders into Nazarene. When Normandy was reestablished in 1744 AN under Theodoric van Orton, many Heartlanders flocked to Ortonia. Thus, they became well-accustomed to Nazarene culture. After the war, the Heartlanders gradually returned to their former homelands. Today, the Heartlanders are among the three largest ethnic groups and face intense discrimination by society due to their origins. By 1750 the Hearltanders were now known as Austrmarkers and were the second largest ethnic group in Normandie.

Other small, settled ethnic groups include the Iridians, Durntkistani, Gralans, and Karnali. These small settled ethnic groups have their own villages and municipalities. Although Normandic and Norse are the official languages of the region, they are able to practice their own culture, even though they are still the official languages of Normandy. In 1750, the Báthorians left Arpad and Normandie to establish their own nation.

Amanlandic and other people of Hurmu Norse descent also live in Normandy.

Culture

Cuisine

The Old Normandie Jarldom had a rich, dairy-based cuisine, and New Normandie still does today. Its rich cuisine was largely due to its fertile lands. The cows grazing on the Normandie plains produced abundant milk, often considered cream, and butter and whipped cream are incorporated into many dishes. Numerous cheeses are also made from milk, the most famous being Manto Cheese, Gruyere, and, most famously, Fig Tree Cheese. The local cattle, Rohan, Pont-l'Évêque, and Neufchâtel, are particularly delicious, and the meat produced from these cattle is quite delicious. New Normandie's harsh climate encouraged people to turn to animal husbandry.

Fruit is also a key component of Normandie cuisine. Apples were widely grown, with orchards often located in Normandie's former southern territories. Apples are often used to produce a slightly fizzy, slightly alcoholic cider. While the region is not known as a historical wine-producing region, cider is frequently consumed with meals. Apples are also used in the production of Fécamp, an after-dinner drink added to desserts and sauces to add a tart flavor. Apple pie is one of Normandie's national dishes. Pears, another important fruit, are used in the production of Eau de Vie. Access to fruit was hampered by the climate of New Normandie, but conditions improved further in Normandie's post-war era, and agriculture was revived with the annexation of Karum.

Seafood has been a staple in Ducal history, and the northern seas yielded a wealth of cod, salmon, tuna, mussels, squid, octopus, and crab. Towns in the southern seas also harvested oysters, mussels, scallops, sole, and lobster. These fish are also occasionally harvested in the northern seas. Normandie's Sunset Sea (now the Rognvald Sea) is particularly abundant in seafood. Traditional dishes include Marmite Vannoise, a creamy seafood stew; Mussels à la crème, mussels cooked with cream butter and herbs; and fruite de mer d'Honfleur, a dish of raw mussels, oysters, cooked shrimp, and lobster served with various sauces. Mussels once gathered on the Isle of Quercy in the former Jarldom of Normandy were highly prized; now, Quercy mussels are cultivated on the Twin Peninsulas. Although nutritious fish products such as tuna, salmon and codfish later entered the Normandie cuisine, they became one of the main seafood products.

Meat-based dishes were frequently consumed by the Duchy, and thanks to Normandie's significant livelihood, livestock farming ensured a constant presence on the table. Normandie's reputation for red meat was further enhanced by the Norman wrestlers. Poultry, particularly chicken, and the local duck, the Norman duck, play a prominent role in dishes such as Canard à la Rohannaise from the Béthencourt Valley. Pork and veal are often cooked with cream and cider, but the Umraists (Narmani and Karumic) do not consume pork. The region was renowned for its "Pré Salé lamb," raised in the salt marshes south of the Mistletoe Forest. While the marshes are now within the Amaland region, Pré Salé lamb is raised on the Arpad Plateau, Newlands, and Karum. Some Karumic recipes have entered Norman cuisine, and lamb cooking techniques have evolved. In present-day central Normandie, traditional dishes include Normandie beef from Vire (south of Béthencort), andouille (in Walsch), and black pudding from Les Chéris, while tripe was a specialty of Bayeaux. Although Les Chéris and Bayeaux lie on the borders of Karnamark, recipes are still practiced by the Norman minority there. Many recipes for red meat were also taken from the Carumid culture, especially Shish kebabs made from lamb and "Billur" ram's balls.

Crepes are a staple breakfast dish in Normandy. They are adopted by both the Norman and Carnevonian peoples. The term crepe refers to both galettes and sweet crepes. Galettes, made from buckwheat (sarrasin), were savory and often filled with ham, cheese, eggs, seafood, or a combination of these. Sweet crepes, made from wheat flour, are filled with sugar, fruit, jam, and chocolate paste. Some varieties resemble ice cream sundaes. A staple of the table, crepes are consumed with grape ale or cider.

Cabbage Tree Cheese, one of Normandie's most famous cheeses, is made in the highlands of Ortonia. Cabbage Tree dye gives the cheese its famous yellowish/orange color, and the plant provides a mild flavor. Milk, rennet, and starter cultures are used to coagulate the cheese. After the curd is cut, it is filled into containers and subjected to propionic fermentation. This process gives the cheese its porous texture. The cheese's ripening process takes up to 120 days, and longer aging can give it a more characteristic flavor. Cabbage Tree Cheese is a staple at breakfasts in Normandie. Another unique cheese is Karumic tulum cheese. It's known for its three-month ripening period and uses sheepskin for its production. The cheese is generally made in Karum and the highlands of Austrmark.

Geography and Climate

Normandy, in general, enjoys a climate shaped by its latitude close to the Arctic Circle and mountainous terrain, often covered in snow throughout the year and experiencing cool summers like highlands. Winters are long and harsh, with heavy snowfall covering much of the interior from November to March.

The region is characterized by extensive alpine meadows, taiga forests, and tundra landscapes, especially at higher elevations. Agricultural land remains frozen for most of the year, and the soil typically thaws only from April onwards. Agriculture begins in spring, resulting in a short growing and harvesting season. Snowfalls provide sufficient nourishment to the lakes and rivers.

Oceanic indentations occasionally form rounded bays and inlets. Ocean breezes soften the coastline and its surroundings. Warm ocean currents make the coastline highly suitable for settlement. Normandy is home to numerous mountain belts, making it an earthquake zone and, over time, capable of generating major earthquakes. Basins form between high plateaus and orogenic mountain ranges, rising from the foothills. Young mountains form in the north, plateaus in the central region, and the peaks of the mountain ranges in the south. Podzol-type soils are found in mountainous terrain, while ceramic soils are found in the plains. Vetch and beet generally grow in these soils.

Karum, annexed to Normandy in 1748, has steppe plains. Because of its proximity to the lake, the climate is mild, allowing wheat, sunflowers, and corn to grow. Karum generally experiences cold and rainy winters and hot and dry summers. Steppe vegetation is present. Rainfall is highest in spring, but annual rainfall is lower than in northern Normandy. Forests of oak and black pine can be seen here and there. The humus in the steppe soils is poor.

Economy

| Currency | Hurmu crown |

|---|---|

| Fiscal Year | 1748 |

| Economic Sectors | Fishing, Mining, Automotive, Services |

The economy of Normandy is a diversified and balanced system combining traditional industries such as fishing, livestock farming, and mining with modern sectors such as manufacturing, automotive production, and services. The economy of Normandy is developing rapidly due to investments. Normandy's mountainous and cold geography greatly restricted its agricultural sector until the annexation of Karum in 1748.

Overview

Normandie’s northern location and harsh winters historically limited large-scale agriculture, leading to an economy long based on fishing, forestry, and mining. In the modern era, the Duchy has embraced industrialization, particularly in the automotive sector, while also developing a strong service industry that supports trade, logistics, finance, and tourism.

Primary sector

Agriculture is primarily practiced in southern Normandy. Due to the climate in the north of the country, agriculture was limited to hardy crops such as barley and rye. Livestock farming, particularly sheep and goat farming, remains important in rural areas. In the south, in the Karum region, wheat, sunflowers, and corn are cultivated extensively.

Fishing and seafood processing constitute a significant portion of the Normandy economy, but coastal towns are largely dependent on cod, herring, and shellfish exports. Numerous salmon hatcheries also exist along the coastline.

The mountainous terrain and plateaus are rich in iron, copper, coal, silver, boron, and, most importantly, ruby. The Lordship of Grisboeuf has a large ruby reserve. Conversely, oil reserves within Normandy are very limited. Importing oil has led to the adoption of alternative resources such as natural gas.

Secondary sector

- Automotive industry: The cornerstone of modern industrial development, the automotive sector is led by three major companies: Petoya, Hektad, and CAN.

- Shipbuilding and heavy industry: With a strong naval tradition, Normandie continues to produce ships, engines, and industrial machinery.

- Defense production: Automotive technologies are also applied to the manufacture of armored vehicles and winter-adapted transport.

Tertiary sector

- Finance and trade: Normandie’s service sector has grown rapidly, with banking and insurance firms concentrated in major cities.

- Tourism: Despite its cold climate, mountain resorts and coastal landscapes attract visitors. Winter sports and cultural festivals contribute significantly to local economies.

- Logistics and maritime services: Given its geography, Normandie is a hub for shipping and transoceanic trade routes. Ports serve both as fishing harbors and export centers for automobiles and industrial goods.

Economic challenges

Normandie’s reliance on imported agricultural goods makes it vulnerable to supply disruptions. At the same time, environmental pressures from mining and industrialization pose risks to its natural ecosystems. Nevertheless, strong exports in the automotive and service sectors continue to balance these vulnerabilities.