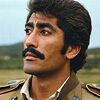

Temüjin Tokaray Erdenechuluun al-Osman

| Temüjin Tokaray Erdenechuluun al-Osman | |

| |

| Physical information | |

|---|---|

| Species | Human |

| Gender | Male |

| Biographical information | |

| Date of birth | 1692 (aged 59) |

| Residence(s) | Swordson (Governorate of Leng) |

| Nationality |

|

Temüjin Tokaray Erdenechuluun al-Osman, born in 1692 AN to Daniyal al-Osman and Ghawetkiin Enkhjargal. Citizen of Hurmu with claim to Constancian nationality by right of Raspurid blood. Scion of the House of Osman. Entered into the registers of the N&H National Sector Party for Constancia from 1700 AN. Bound by blood obligation to serve in the Hurmu Peace Corps from his 18th birthday. Pledged to wed Azita Bakker (1701- ) on her 16th birthday. Fled from his duties, 6.XI.1717. Accorded the chance of repentance through service by the Benacian Union in the same month as his disgrace.

Biography

Early life

Concurrent with his education at the Sarayzenana, Temujin was enrolled with the Constancian Humanist Vanguard in Raspur for his indoctrination into Humanism. This association would see him affiliated to the Modan Brigade between 1704 and 1710, during which time the Home Guard was called out as part of Operation Landslide (1706-1708). Although situated in Raspur for most of the conflict, provision was made for Temujin to spend a fortnight in the summer of 1707 with the 1st Demi-Brigade of the Modan Brigade, which at that time was positioned as a blocking detachment behind a division of the Molivadian Home Guard, a formation with notably fragile morale. As Temujin during this time was honoured with responsibility for organising a firing squad to dispose of suspected deserters and partisans, he subsequently received the Red Hand, an enamelled lapel badge featuring a blood-red hand held palm upwards. This honour secured his standing in the N&H movement.

Hurmudan service

Enrolled with the Hurmu Peace Corps in 1710 AN, he completed basic training before being accepted into the Peace Academy, where he studied for a bachelor's degree in peacekeeping at the Kaupang campus. His academic career was reportedly underwhelming. Although engaged with the subject, his deficiency in numeracy, as well as a tendency towards idleness, marked him out as a mediocre student and he graduated in the bottom third of his class.

Samhold

Temujin found himself posted in 1713 AN to the undeniably bleak island of Samhold as part of the 71st Depot & Logistics Regiment. Although a posting with few immediate prospects for a fresh officer of the peace, Samhold did afford Temujin an outlet in that he was able to organise the Samhold Cadre of the Coalition for Democratic Humanism, having been a mere regular member of a regional cadre during his time in Kaupang.

Whilst being the son of the former Prime Minister had a definite advantage in securing his position as Regional Cadre Leader on the island, it did not endear him to that portion of the population which had by that point between twice exiled on account of Humanism, firstly as a consequence of the Second Elwynnese Civil War and subsequently following the annexation of the Warring Islands by the Benacian Union.

Moorland

The conduct of Temujin in Moorland showed him to be wholly unsuited to any serious position of authority. From his dithering and procrastination in establishing his command, to his fixation with bureaucratic and organisational trivialities, to say nothing of the ease with which he was deftly manipulated by the barbarous Green Einhorns into becoming an unwitting supporter of the Confederacy of the Dispossessed. He would subsequently be described by no less a personage than his own father as a "contemptibly sensuous idiot".

He would eventually, towards the end of the tenth month of 1717 AN, receive an explicit order from Jamshid-e Osman to return immediately to Huyenkula via the Port Esther Gate to account for his conduct in office. The occasion for his disgrace and recall was the Prime Minister's discovery that his Minister had appointed a "feral barbarian" (in Jamshid's phrasing), Mantric, son of Dunric, as the head of his administration in the district.

After a few days of prevarication, Temüjin eventually departed Newhaven for Port Esther, realising that he had never been held by the Green Einhorns in such esteem as they had led him to believe, indeed not a one of them had been willing to inconvenience themselves by interceding to prevent his recall. Arriving in Port Esther, Temüjin, unwilling to face the disgrace of his recall appealled to the Benacian Union for asylum. To his enduring misfortune, his appeal was accepted and he duly became classed as a protected person.

Accordingly, Moorland was left in the possession of a native chieftain, the nominal commissioner, without even an inept minister to hold him to account.

Benacian Union

Considering the infamous conclusion to his tenure in Moorland, Temüjin found it regrettably expedient to claim asylum in Benacian Union upon his return to Port Esther in the winter of 1717 AN. He would perhaps rue his decision as, without the protection of his father or of this government, the authorities of the Warring Islands Special Autonomous Region swiftly arranged for their unexpected asylee to be transferred to Chryse via the Hurmu Gate Network and into the protective custody of the Magisters-Carnifex. That the Hurmudan authorities felt no need to interfere with this transfer could be remarked upon in its own right.

A period of penance

As a protected person, he would, within twenty-four hours of his arrival, be brought to the Palace of Botha. There he would in due course learn his fate from Ayesha al-Osman, the Commissioner for Foreign Affairs and a woman wrathful, in the extreme, towards a kinsman who had disgraced the House of Osman and caused considerable embarrassment to the Union-State in its dealings with Hurmu. The interview, when it occurred, was not a success, and Temüjin would spend the remainder of 1717 AN and the entirety of 1718 AN assigned to the Swordson Reform Settlement in Leng. The period of penitential labour, which had been intended to address some of the more fundamental flaws in his character, had exposed him to the harshness of a boreal environment beyond his comprehension, extended periods of solitary confinement interspersed with group struggle sessions under the guise of conditioned social harmonisation, and the worst aspects of the mundane cruelty of daily life in a penal colony at the far edge of the world.

Having been isolated from outside contact for over a year, he would not learn of his father's death in 1717 AN until his return to the Benacian mainland in the first month of 1719 AN.

His return to the mainland had been occasioned by a deterioration in his health towards the end of XV.1718 AN. The combination of arduous menial labour, an inadequate diet, and the periods of prolonged isolation alternating with vicious sessions of collective self-criticism alongside the population of the reform settlement, had undermined his constitution to the point where a medical evacuation was deemed necessary. Having been airlifted to La Terre via Anun, Temüjin had been placed in a guarded wing of La Terre's designated hospital for protected persons, where learning the news of his father's death over a year prior did little to aid his recovery. An acolyte of the Zurvanite tradition from the United Ecclesiastical Corporation of Benacia was assigned to him in order to ensure that he continued his work of penance during the mandated month long convalescence period. Unfortunately for Temüjin, this caseworker, Bahram Gaspar, was an enthusiastic advocate for salvation via the mortification of the flesh.

Administrative issues

By now the appeals of his mother, which had begun shortly after the death of Daniyal al-Osman had removed the objections to her mercy, had finally begun to percolate through the convoluted and bifurcated hierarchies of the Union-State.

It had been as early as the third month of 1718 AN when a petition for the release of Temüjin had duly been transmitted, after some deliberate time wasting, by the Commission for Foreign Affairs to the Magisters-Carnifex. The magisters themselves complained that it did not lie within their gift to pardon an individual, quite the opposite in fact, and their agents in Chryse duly passed the petition to the Benacian Censorate.

Unfortunately, as Temüjin had been assigned to the status of a protected person as a foreign national, he had neither signed the Union Covenant nor been recorded as a recusant, and as such the Censorate disclaimed all knowledge of the individual and returned the petition to the magisters, declined on the grounds of being invalid. The magisters, not wishing to report to the Lady of Chryse that the captive son of an eminent foreign ally had been misplaced as a nonperson, duly resubmitted the petition to the Censorate with an attached docket containing the pertinent details recorded concerning Temüjin at the point of his induction, and a copy of the instruction concerning the transfer of Temüjin from Chryse to Leng. The Censorate countered that the matter remained out of their hands, as the individual had not been registered via the appropriate channels. If this Temüjin had indeed been, as was suggested, transferred to a reform settlement, he should first have undergone processing at a reception centre controlled by the Benacian Labour Reserve in Elluenuueq. The petition was again rejected, with the curt directive to address it to the commandant of the Swordson Reform Settlement.

The Commandant of Swordson, rejoicing in the name of Horst Wenck, was bemused to receive on 21.VI.1718 AN a many times overstamped petition for the release of the protected person Temüjin Tokaray Erdenechuluun al-Osman. For Horst this was an unwelcome missive, inasmuch, as far as he was concerned, the release of a foreign national held on the authority of the Commissioner for Foreign Affairs could only be authorised by that selfsame individual, and nowhere could he identify a positive instruction from Ayesha al-Osman to undertake that action. Rather than reject the petition outright, he passed the correspondence up the chain to the Commandant-General of the Benacian Labour Reserve, or rather to the Outer Office of the Commandant-General, which served to screen that hallowed individual from the majority of the routine administrative communications which flooded into the centre from periphery.

Now, it was at this point, around the seventh month of 1718 AN, that the petition and its associated correspondence appeared to misplaced or misfiled during the reorganisation of the Outer Office - which was being divided up into a number of separate directorates and a central secretariat. It was this secretariat, containing the correspondence bureau, which was required to pass the petition on to a desk officer in the newly formed Directorate for Reform Settlements. It instead appeared to have been transmitted to the Archives Office, although the correspondence chain concerning the transfer was seemingly lost. In spite of the junior clerical staff and their supervisors being subsequently transferred into the custody of the Magisters-Carnifex[1], no satisfactory explanation for this breakdown in communication has been obtained. It was therefore considered an instance of human error combined with poor management processes and lax oversight.

Education

- Education & Indoctrination Service of Raspur (Raspur)

- 1700–1704: Saraymardana (primary school, boys)

- 1704–1708: Dabirestân-e Andarûn (secondary school, boys)

- Peace Academy (Hurmu)

- 1710–1713: Bachelor's Degree in Peacekeeping (2:2)

- 1716–1717 : Master's Degree in Peacekeeping (correspondence course, terminated with his expulsion from the course)

Career

- 1700–1701: Junior Cadet (Young Humanists League, Constancia)

- 1701–1702: Cadet (Young Humanists League, Constancia)

- 1702–1703: Senior Cadet (Young Humanists League, Constancia)

- 1703–1704: Senior Cadet Leader (Young Humanists League, Constancia)

- 1704–1705: Vanguard Section Leader (Modan Brigade, 1st Vanguard Division)

- 1705–1706: Vanguard Standard Bearer (Modan Brigade, 1st Vanguard Division)

- 1706–1707: Vanguard Watchmaster (Modan Brigade, 1st Vanguard Division)

- 1707–1710: Vanguard Troop Leader (Modan Brigade, 1st Vanguard Division)

- 1710–1713: Regional Cadre Member (Kaupang Cadre, Coalition for Democratic Humanism)

- 1710: Trainee of the Hurmu Peace Corps (112th Basic Training Regiment, Hurmu Peace Corps)

- 1710–1713: Aspirant Officer of the Peace (148th/1st Cohort of the Peace Academy, Hurmu Peace Corps)

- 1713–1716: Officer of the Peace (71st Depot & Logistics Regiment, Hurmu Peace Corps)

- 1713–1716: Regional Cadre Leader (Samhold Cadre, Coalition for Democratic Humanism)

- 1716–1717 : Chief Superintendent of the Peace (act.)

- 1716–1717 : Regional Party Leader (Moorland Cadre, Coalition for Democratic Humanism)

- 1716–1717 : District Commissioner (Moorland)

- 1716–1717 : Minister for Moorland (Cabinet of Patrik Djupvik & Cabinet of Jamshid-e Osman)

- 1717.XI.6: Effective date of induction as a protected person of the Benacian Union.

- 1717.XI.7: Date of transfer to Chryse as a guest of the Magisters-Carnifex.

- 1717.XI.12: Date of dishonourable discharge from the Hurmu Peace Corps.

- 1717–1719: Penitent labourer of the Benacian Labour Reserve (Governorate of Leng)

Awards

Offspring

Note

- ^ These individuals were, after a full review, accorded the merciful sentence of 18 months penitential labour on the island of Naudia'Diva