Sanaman language

|

This article or section is a work in progress. The information below may be incomplete, outdated, or subject to change. |

| Xele sanamali | |

| Spoken natively in |

|

|---|---|

| Language family |

|

| Writing system | Machiavellian |

| Dialects | Sani, Ama |

| Official status | |

| Official language in |

|

| Regulated by | Konselyo Xele Sanamali |

| Language codes | |

| MOS-9 codes | sn |

The Sanaman language, xele sanamali, formerly called Lakhesian by the colonial power Shireroth and Sani/Ama, is a Cosimo-Benacian language spoken by approximately 80 million people in Sanama and Talenore. Sanaman is an ergative-absolutive agglutinating language with a mainly SOV word order. It has two orthographic standards, called Sani and Ama. It is also related to the divergent Estarisan. It is an official language in Talenore and the main official language in Sanama.

History

The Sanaman language is the common name for the Sani and Ama dialects of the contemporary Cosimo-Benacian language spoken in and around Sanama and Talenore. The two dialect groups are almost entirely mutually intelligible, differing only slightly in orthography, word choice and pronunciation. While speakers of a western dialect of Ama and an eastern dialect of Sani might struggle to understand each other in certain circumstances, exposure to different dialects increase understanding dramatically. Some Sanis and Amas push back against the notion of a common language, stressing the many perceived differences between the two standards. In 1680 the new government lead by the United Nationalist Alliance started promoting the notion of a common Sanaman ethnicity, comprising both the Ama and the Sani peoples. The federal census of 1680 also classed the Sani and Ama as Sanaman for the first time. As of 1750, the Ama literary standard has mostly fallen into disuse, with the Sani standard being dominant.

Official status

Sanaman is an official language in Sanama and recognised for local official use in Talenore.

Distribution and usage

Sanaman is spoken natively in western, central, southern and southeastern Sanama, in the areas traditionally called Sanilla and Amarra. It has its strongest position outside the large cities. In rural areas and smaller cities and towns, it is by far the majority language. In larger cities, like Niyi, it has a much weaker position, usually in favor of Istvani. In the entire country of Sanama, 70 percent of all people speak Sanaman as their first language. A colloquial mixed register between Sanaman and Istvanistani called Sanastani is also very common, especially in urban area among younger people. Codeswitching between the two languages is also common.

Phonology

Consonants

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Post-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plosive | p | t | k | q | ||||

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||||

| Trill | r̥ r | |||||||

| Fricative | ɸ | θ | s | ʃ | x | h | ||

| Approximant | ʍ w | j | ||||||

| Lateral fricative | ɬ | |||||||

| Lateral approximant | l |

Where consonants appear in pairs, the left is unvoiced and the right is voiced. /r/ is often realised as a tap or flap /ɾ/ in certain environments.

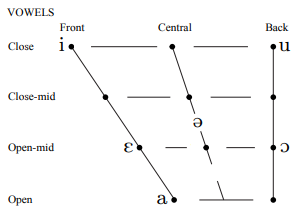

Vowels

Sani has six vowel phonemes. They do not contrast for length or nasality. The Sani schwa vowel is transliterated as Ë, while the E vowel varies between /e/ and /ɛ/ depending on environment.

Phonotactics

Orthography

Sani

| Orthography | A | E | Ë | F | Ff | H | I | K | L | Lh | M | N | Ng | O | P | Q | R | Rh | S | T | U | W | Wh | X | Y | Sh |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phonology | a | ɛ-e | ə | ɸ | θ | h | i | k | l | ɬ | m | n | ŋ | ɔ | p | q | r | r̥ | s | t | u | w | ʍ | x | j | ʃ |

Ama

| SAN | Aa | Ee | Ii | Oo | Uu | Ëë | Pp | Mm | Tt | Nn | Kk | Ngng | Rhrh | Rr | Ff | Ffff | Ss | Shsh | Xx | Hh | Ww | Whwh | Yy | Ll | Lhlh | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMA | Aa | Ee | Ии | Oo | Уу | Әә | Пп | Mм | Tт | Hн | Кк | Ққ | Ңң | PЬpЬ | Pp | Фф | ФЬфЬ | Cc | Шш | Xx | Ҳҳ | Bв | BЬвЬ | Йй | Лл | ЛЬлЬ |

Morphology

Sanaman is an agglutinative suffixing language with head-final clauses. The neutral argument order is subject-object-verb (SOV), where the verb is always in the final position. Marking for case, number, aspect, mood and other suffixes always attach to the head. Sanaman is consistently ergative-absolutive.

Nouns

Nouns in Sanaman are inflected for number and case and form the core of argument marking in the clause. Nouns are strictly dependent-marked: all relations involving nouns are marked in the nominal morphology and not through verbal agreement. The standard structure of a noun phrase head is:

- Noun stem

- Optional plural marker

- Case suffixes

- Separate optional postpositions

Plural marking always precedes the case marking. Case only attaches to the head noun of the noun phrase. Sanaman only explicitly marks plural number, singular is unmarked. The plural marker is used for both nouns and pronouns. Plural marking is not mandatory when it can be inferred from context. The plural is marked with the -qo suffix.

| Word | Singular | Plural | Ergative case |

|---|---|---|---|

| house | pahay | pahayqo | pahayqoya |

| island | hareffa | hareffaqo | hareffaqoya |

Sanaman is an ergative-absolutive language, where the subject (agent) of a transitive verb takes the ergative case, while the direct object of a transitive verb and the subject (patient) of an intransitive verb takes the absolutive case. Case markings only attach to nouns and pronouns. The third core case is the genitive, marking possessors.

There are also several spatial and semantic cases:

- Ablative: Source as well as standard of comparison in comparative clauses.

- Allative: Goal, also recipient.

- Inessive: Inside something.

- Elative: Going out from something.

- Illative: Going into something.

- Adessive: On, at or near something.

- Locative: General location, also used for ”outside” in combination with a postposition.

- Instrumental: Means, and also demoted agent in causatives.

- Comitative: Accompaniment.

Cases are used both for syntactic role as well as spatial or semantic relations. Postpositions can follow case-marked nouns for added precision. Indirect objects, recipients and goals are marked with the allative case and appear before the direct object in neutral clauses. Default order with indirect object is:

Agent-ERG Recipient-ALL Theme-ABS Verb

The allative is the default case for recipients, after historically absorbing the dative functions through semantic overlap between goal and recipient. Additional postpositions can follow the allative for added nuance. Indirect objects can also be fronted to the first position in the clause for topicalization or focus.

| Case | Core use | Suffix | Example | Annotation | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ergative | Marks the subject (agent) or ”doer” of a transitive action. | -a, -ya | letiya whaso matë | leti.ERG whaso.ABS matë.IMPERFECT | The man sees a bird |

| Absolutive | Marks the subject (patient) of an intransitive action and the direct object of a transitive action. | – | letiya whaso matë nati esatus |

leti.ERG whaso.ABS matë.IMPERFECT nati.ABS esat.CONT |

The man sees a bird The woman is standing |

| Allative | The core function is to show movement towards a place, recipient, or target, as well as recipients of transfer. | -s, -os | leti shukakos ngaran letiya natis rhimus letiya natis posa taman |

leti.ABS shukako.ALL ngar.PERF leti.ERG nati.ALL rhim.CONT leti.ERG nati.ALL posa.ABS tam.PERF |

The man went to the city The man is speaking to the woman The man gave a cat to the woman |

| Ablative | Ablative shows source, movement away from something, origin. | -ir, -rir | leti shukakorir talan | leti.ABS shukako.ABL tal.PERF | The man came from the city |

| Inessive | The inessive shows location inside, being contained. | -tan | nati pahaytan ayalusla | nati.ABS pahay.INESS ayal.CONT.INDSTR | A man is sitting in the house |

| Elative | The function of the elative case is to show movement out from inside something. | -sa | anati pahaysa talla | anati.ABS pahay.ELAT talan | The child came out of the house. |

| Illative | The illative shows movement into something. | -ta | anati pahayta ngaran | anati.ABS pahay.ILL ngar.PERF | The child went into the house. |

| Adessive | The adessive case marks location on or in the immediate vicinity of something. | -hil | patoqo panehil | pato.PLU pane.ADESS | There are rocks on the beach. |

| Locative | The locative case shows general location, and is used when the more specific spatial cases are not intended. | -ina | nati pahayina | nati.ABS pahay.LOC | The woman is at home. |

| Instrumental | Marks the instrument or means by which an action is performed. | -kan | leti kotaqokan kotus | leti.ABS kota.PLU.INST kot.CONT | The man is rowing with oars. |

| Comitative | The comitative case marks a participant that is together with the subject. | -kë | nati anatikë pahayina | nati.ABS anati.COM pahay.LOC | The woman is at home with her son. |

Noun phrases in Sanaman are head-final. This means that the main noun of the phrase is placed last, with the following elements preceding it, from the front of the clause to closest to the head:

- Relative clauses / Genitive modifiers

- Demonstratives

- Numerals and quantifiers

- Adjectives

- Noun head

Example:

| Sentence | Annotation | Meaning | Literal |

|---|---|---|---|

| to shukako pahayen natili qale puti anatiqos | DEM shukako pahayë.NOM nati.GEN qale puti anati.PLU.ALL | to the many good daughters of the woman who lives in the city | this city living woman's many good daughters-to |

Demonstratives can also function as determiners and thereby mark definiteness. If no demonstrative is used, definiteness is inferred from context or focus fronting. Determiners can also be doubled, with the double following the head noun, for added emphasis.

| Demonstrative | Meaning |

|---|---|

| to | This |

| ya | That (in view) |

| mo | That (referred) |

Sanaman has three strategies for compounding. Lexical compounds are used for titles, more permanent roles and inherent categories. They are formed by words being fused together. As with all noun phrases, they are head-final, with the preceding words modifying the head noun by narrowing its meaning to create a new concept. Ad hoc participal phrases are synthetic open phrases that turn an action into a temporary title. The object and the verb constitute a phrasal adjective that attaches to the head noun. The verbal root takes a nominalizer -en/n to create an acting noun (an "eater"), which then modifies the head noun. Finally, genitive phrases function as they do regarding inalienable possession and similar to Istvanistani. The possessor takes the genitive case and precedes the possessed noun.

- Lexical compound: natianati, daughter (lit. "female child").

- Ad hoc participal phrase: pikas kayinen leti, man who eats food (lit. "food eating man").

- Genitive phrase: letili pikas, the man's food.

Prounouns

Sanaman has a small class of personal pronouns. They behave like nouns and take the same plural and case markings. The system shows person and clusivity, but does not show gender or animacy. Inclusive and exclusive first-person plural pronouns are separate lexical items and not pluralized forms of the singular and do not take the plural suffix. They derive from a demonstrative meaning "that one". Reflexivity, an action performed on the actor ("the man saw himself"), is handled with the reflexive voice on the verb, not on the pronoun. Possessive pronouns are not a separate category, instead possession is expressed by the genitive case. Pronouns also take the same case markings as nouns across all categories. Pronouns, especially those in the absolutive case, can be omitted when their identity can be inferred from context. Ergative pronouns are retained more often due to their added significance.

| Person | Number | Snm. | Ist. |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | sing. | ako | I |

| plur. incl. | akoma | we (including the person the speaker is talking to) | |

| plur. excl. | akori | we (excluding the person the speaker is talking to) | |

| 2nd | sing. | ika | you (singular) |

| plur. | ikaqo | you (plural) | |

| 3rd | sing. | ffa | he, she, it, they (singular) |

| plur. | ffaqo | they (plural) |

Possession

Sanaman has two forms of possession: inalienable possession cannot be revoked, the possession is inherent, asin the sentences "the man's foot" and "the mother's daughter". The other form, alienable, can be revoked, as in the sentence "the girl's bike". Inalienable possession is marked directly on the possessor with a genitive suffix followed by the possessed noun, while alienable possession is expressed by the possessed noun taking a genitive linker clitic followed by the possessor taking the genitive case. The genitive case always attaches to the possessor, not the noun being possessed. Possession can also indicate temporary relationships between two distinct entities.

- Inalienable possession: letili anati, the man's child.

- Alienable possession: pahayxa letili, the man's house.

Adjectives and modifiers

Adjectives in Sanaman are distinct from nouns and verbs, but they are morphosyntactically simple, since they do not inflect for number, case or agreement. All grammatical relations involving adjectives are expressed through position within the noun phrase and, where relevant, through discourse-driven fronting. They may also function like a predicate without a copula under the same conditions that allow copula omission generally. For example, the phrase for "I am Sanaman" is ako Sanamati, omitting a copula. Sanaman is consistently head-final within the noun phrase. Adjectives precede the noun they modify in the neutral order. Adjectives must appear after demonstratives and quantifiers. The standard internal structure of the noun phrase is:

(Discourse particles) - Demonstrative - Quantifier/numeral - Adjectives - Noun (head) - Plural - Case - Postpositions

[Examples]

When there are multiple adjectives, they follow a preferred order that can be violated for style, emphasis or contrast, especially in literature or rhetorics:

- Demonstratives

- Quantifiers/numerals

- Evaluative adjectives (good, bad, important etc.)

- Size, age, shape

- Color

- Material or origin

- Noun

Adjective stacking is unrestricted and common, particularly with evaluative and descriptive adjectives. No conjunction or other linker is needed. In specific registers, primarily legal and commercial language, a limited class of adjectives may follow the noun. These adjectives do not describe inherent qualities but instead institutional or categorical status (e.g. "official", "legal", "fixed", "standard"). This placement is an exception brought about from contact with Cisamarrese. In predicative position, adjectives behave like nominal predicates. When the copula is omitted, the adjective directly follows the subject noun phrase. All distinctions normally carried by a verb, such as voice, aspect and mood, are only present when a copula is used.

Numerals and quantifiers

Numerals and quantifiers do not inflect, they do not take case, number or any other agreement marking. Case marking appears only once on the noun head. Numerals and quantifiers appear after demonstratives and before adjectives. Numerals do not trigger automatic plural marking on the noun head, instead the marker is optional, used when plurality is not already evident from context or the numeral itself.

Sanaman has a mixed numeral system, influenced by historical development and contact. The base numerals are 1-12, 13-19 are formed as ”12 and X”. 20 is a lexicalized compound that derived from ”12 + 8”. Higher multiples of ten are constructed through multiplication and addition, such as ”two-of-twenty”, ”twenty-and-ten”. The word for ”hundred” is borrowed from Praeta, while the word for ”thousand” is borrowed from Cisamarrese. Ordinal numbers are formed with the iqa suffix attached to the numeral, except for first three numerals, which have separate lexical ordinal forms.

Quantifiers, such as ”many”, ”few”, ”all” or ”some” take the same syntactic slot as numerals and are mutually exclusive with them unless they are explicitly coordinated. Quantifiers can also be used as independent noun phrases when it can be understood from context, they then act like noun heads and can take case marking. Numerals and quantifiers do not encode definiteness, it is instead inferred from discourse context, case use, topicality or marked explicitly by demonstratives that double as determiners. When a demonstrative is present, it modifies the entire noun phrase. Under the general rule for fronting, numerals and quantifiers can be moved to the clause-initial position for contrast or emphasis. It does not change the grammatical role of the word.

Verbs

In Sanaman, almost all verbs are highly regular, except for "sumë", to be, and "puxë", to do, to make. Verbs also have a rich morphology, and just like nouns they are strictly head-final. All morphology is suffixing, and the verb is always clause-final in neutral syntax. Grammatical relations are expressed with case and word order, there is no verbal agreement for person or number. The suffixes follow a certain order, and deviation is not allowed. Not all slots are required, but when they appear, they must do so in the proper order. Sanaman has both aspect and mood, but does not show tense on the verb. Temporal aspects are inferred through aspect, mood and/or temporal postpositions.

There are no verb classes in Sanaman, but some verbs undergo slight phonological changes in certain situations. All verbs end in -ë, and in all aspects except the general imperfective, the stem used drops the final ë. When the stem ends in a stop, the stop undergoes lenition, to avoid illegal consonant clusters. In cases where the stem ends in two consonants, when the stem takes a suffix, an epenthetic schwa is inserted between the consonants. These changes are regular and predictable. In addition to this basic morphology, there are two irregular verbs.

| Example | Stem | Alteration |

|---|---|---|

| pipë /pipə/ |

pip- | pifna /piɸna/ |

| matë /matə/ |

mat- | maffna /maθna/ |

| makë /makə/ |

mak- | maxna /maxna/ |

| raqë /raqə/ |

raq- | raxna /raχna/ |

| qurtë /quɾtə/ |

qurt- | qurëffna /quɾəθna/ |

| xalmë /xalmə/ |

xalm- | xalëmna /xaləmna/ |

Verbal structure

- Root/stem (required)

The lexical verb. Two verbs are irregular and exhibit stem alterations depending on aspect. Regular verbs have a single stable stem, but some phonemes do undergo lenition in certain situations.

- Voice/valency (optional)

Derivational morphology that changes the argument structure of the verb, such as causative and passive. These suffixes change which cases nominal arguments take. A neutral unmarked verb is in the active voice. In an active transitive clause the agent (subject) is marked with the ergative case and the patient (direct object) with the absolutive case. In intransitive clauses, the only argument is absolutive.

The causative voice increases valency, the number of arguments, by adding a new external argument, the causer. The causer becomes the new agent marked with the ergative case. The original agent, the causee, is demoted. The original patient remains absolutive. Case assignment depends on transitivity. In the intransitive causative, the causee takes absolutive case since there are no other patients, while the causer takes the ergative. In the transitive causative, the causee is demoted to the instrumental case, while the original patient remains absolutive.

The passive removes the agent from the status of core argument and reduces transitivity. The original agent is demoted from ergative to ablative. The patient remains absolutive and becomes the only core argument. The verb behaves as intransitive.

The adversative voice is a historical fusion of causative and passive. It expresses situations where the subject is negatively affected by an event caused by someone else, often with unwanted connotations, "to have something done to you".

The applicative/benefactive introduces an additional participant, usually a beneficiary or affected party. The applied argument becomes absolutive and the original absolutive is demoted to the instrumental case.

The reflexive voice indicates that the agent and patient is the same, as in acting on itself. No separate reflexive pronoun is used, instead reflexivity is marked on the verb. The subject remains ergative in transitive reflexives, but acts on itself.

- Aspect (required)

Aspect is required on all finite verbs and show the internal time structure of the action or event. The aspects are perfective, habitual, continuous and general imperfective, generally called "null aspect" since it does not take a suffix. It interacts with and causes irregular stem alterations. The perfective aspect shows an event or action as limited in time and complete. Typical uses include completed past actions, single events and results when supported by context. Perfective is commonly used in narratives, reports of completed actions and sequential clause chaining. The habitual aspect shows customary, repeated or characteristic actions over time. Typical uses include general habits, regular activities and long-term tendencies. The habitual aspect often combines with the weak indicative mood for general statements and with conditional mood for general claims about imagined alternatives. The continuous aspect presents an event or action as ongoing, in progress or unfolding at a specific time. Typical uses include actions currently ongoing, simultaneous background actions and temporary states. In clause chaining, the continuous aspect marks that actions take place simultaneously, "while doing X...". The null or general imperfective aspect is an unmarked imperfective used for general, stative or timeless situations. Typical uses are states, "to know", "to be", "to have", general truths and unbounded events. Copula omission in Sanaman is restricted to clauses with null or habitual aspect.

- Core mood (optional)

Mood and modality in Sanaman show the speaker’s attitude toward the proposition, including factuality, hypotheticality, command, desire and knowledge. The morphology is layered, with peripheral moods only attaching to core moods. Marking follows aspect and precedes negation.

Core moods define the speaker’s intent behind the statement in the clause. The strong indicative marks factual, asserted statements presented as true by the speaker. Uses include presentations of information, oaths and formal assertions and legal or religious language. The weak indicative shows reduced faith in the truth of the proposition. Typical uses are reported information, beliefs and assumptions and probable but uncertain events. It often occurs together with evidential markers and peripheral moods indicating knowledge. The subjunctive mood marks non-factual or hypothetical events. It is typically used for if-statements, desired or feared outcomes and embedded clauses under verbs showing intention, doubt or obligation. The subjunctive has a fused negative form expressing meanings such as ”should not” or ”not wanting to”. The conditional mood expresses statements about what would happen under certain conditions, usually in if-then statements. Typical uses are hypothetical outcomes, polite statements and speculation. The optative mood expresses wishes or hopes, while the imperative make direct commands. Uses include orders and instructions. Negation combined with the imperative give a prohibitive meaning, as in ”do not speak!”.

- Peripheral mood (optional)

There are four peripheral moods that can attach to a core mood. They add extra nuance to a statement. They are less widely used and often used in specific registers. While they technically can attach to any core mood, in practice they are restricted to only certain core moods. This also varies across verbs due to plausability. The potential mood shows possibility or ability, with a specialized negative form expressing inability (”cannot”). The admirative states surprise, while the hortative marks encouragement or politely encouraged action without command. Not all combinations of aspect, core mood and peripheral mood are equally common. Combinations using the strong indicative are the most widely used. Peripheral moods combined with core moods outside the indicative are often archaic, formal or stylistic.

- Negation (optional)

Negation is expressed through a suffix that modifies the entire verb. To negate an entire clause, an extra-verbal negation word is needed. Certain moods historically fused with negation, resulting in a few specialized negative forms.

- Question/focus (optional)

A historical interrogative particle that merged with verbal morphology. It marks yes/no questions and can be combined with the negative suffix.

- Evidentiality (optional)

The evidentiality suffix shows information source, such as direct perception, inference and hearsay. They often overlap with certain mood markers, such as weak indicative, dubitative or potential, but remain a distinct category.

Voice and valency

Aspect

Mood

Negation and question

Evidentiality

| |||||||||||||||||||||||