Chartered settlement companies (Nouvelle Alexandrie)

| Chartered Settlement Companies of Nouvelle Alexandrie | |

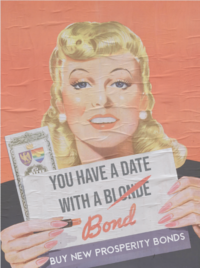

A poster promoting New Prosperity Bonds, issued in part through settlement companies. | |

| Formation | 1686 AN–1693 AN |

|---|---|

| Type | Chartered companies |

| Purpose/focus | Territorial colonization and development |

| Headquarters | Various (see individual companies) |

| Membership | 5 major companies |

| Key people |

|

| Parent organization | Infrastructure Development Bank |

| Affiliations | New Prosperity Plan |

| Budget | NAX€1.645 trillion (total appropriations) |

| Remarks | Primary vehicles for New Prosperity Plan territorial expansion |

Chartered settlement companies in Nouvelle Alexandrie were government-chartered entities established between 1686 AN and 1693 AN to colonize, settle, and develop new territories as part of the New Prosperity Plan. These companies combined public authority with private capital to execute the Federation's ambitious territorial expansion across Eura, Keltia, and the Skerry Isles. Five major companies were chartered: the New Luthoria Settlement Company, the Caputian Resettlement Authority, the Lyrican Settlement Company, the Palmas Settlement & Construction Company, and the Wechua-Santanderian East Keltian Company.

The settlement company model in Nouvelle Alexandrie drew upon the successful precedent of the Societe General d'Alduria, which had led the creation of Alduria in 1669 AN. The New Alexandrian companies operated as public-private partnerships, with the federal government holding majority stakes while private investors provided capital in exchange for land rights, commercial concessions, and preferential access to opportunities in newly developed territories. These companies were granted extraordinary powers including temporary foreign affairs authority, the ability to levy certain taxes, and responsibility for establishing initial governance structures in their assigned territories.

Between 1686 AN and 1693 AN, the settlement companies received total appropriations of approximately NAX€1.645 trillion, of which NAX€496 billion was directly expended on colonization activities. The companies facilitated the integration of Santander, Valencia, North Lyrica, South Lyrica, Isles of Caputia, New Luthoria, Islas de la Libertad, and portions of eastern Keltia into the Federation. Following the completion of their primary settlement missions, the companies were gradually wound down between 1698 AN and 1705 AN, with their assets transferred to regional governments and residual obligations absorbed by the Infrastructure Development Bank and Federal Special Funds.

The settlement companies remain significant in New Alexandrian financial history for their role in the Federation's rapid territorial expansion and for the complex financial legacy they left behind. The gap between appropriated and expended funds, combined with various guarantee obligations and incomplete project handovers, created contingent liabilities that would influence fiscal policy for decades.

Historical background

| Region | Integrated | Settlement Company |

|---|---|---|

| 1687 AN | New Luthoria Settlement Company | |

| 1691 AN | New Luthoria Settlement Company | |

| 1687 AN | Caputian Resettlement Authority | |

| 1687 AN | Lyrican Settlement Company | |

| 1687 AN | Lyrican Settlement Company | |

| Notes: Santander and Valencia (both 1686 AN) were integrated through direct federal action prior to the settlement company system. The Palmas Settlement & Construction Company expanded territory within North Lyrica (Talamthom). The Wechua-Santanderian East Keltian Company's eastern Keltian activities did not result in new Regions during its operational period, but instead led to the expansion of Santander and Valencia. | ||

The chartered settlement company model employed by Nouvelle Alexandrie was directly inspired by the Societe General d'Alduria, which emerged from Punta Santiago in 1669 AN to lead the creation of Alduria in Eura. The Societe General was established as a public-private partnership to provide a new homeland for the diasporas from Alexandria and Caputia following the Alexandrian flu and subsequent political upheavals. The Aldurian government held majority shares, ensuring state control over the colonization process while benefiting from private investment and expertise.

The Societe General proved remarkably successful. It recruited settlers, established infrastructure, promoted trade, and laid the foundations for what would become one of Eura's most prosperous nations. Many private lands in Alduria continued to be managed "in trust" by the Societe General decades after initial settlement, reflecting the company's lasting impact on regional development. This success provided the template that Alejandro Campos and the Council of State of Alduria-Wechua would adapt for the New Prosperity Plan's territorial expansion program.

New Prosperity Plan framework

When the Federation of Alduria and the Wechua Nation was established in 1685 AN, President of the Government Alejandro Campos and the Coalition for Federal Progress launched the New Prosperity Plan to address the immediate social, economic, and military needs of the nascent Federation. The Plan encompassed economic development programs, infrastructure construction, social welfare initiatives, and territorial expansion. The Wechua Planning Commission, which had successfully executed the Wechua Five-Year Plans in 1673 AN, 1679 AN, and 1685 AN, provided crucial institutional expertise for the Plan's development.

The territorial expansion component of the New Prosperity Plan required a mechanism that could mobilize substantial resources, attract private investment, coordinate complex logistics across vast distances, and establish effective governance in areas designated as the Green. The chartered settlement company model offered all these capabilities while distributing risk between public and private sectors. The Federal Constituent Assembly authorized the creation of such companies through enabling legislation in early 1686 AN, establishing the legal framework for their operation.

Legal framework

Settlement companies in Nouvelle Alexandrie were established through royal charters issued by H.M. the King on the recommendation of the Council of State. Each charter defined the company's territorial mandate, corporate structure, capitalization requirements, powers, and obligations. The charter process required approval from both the Council of State and the relevant committee of the Federal Constituent Assembly (and later the Cortes Federales), ensuring legislative oversight of the extraordinary powers being delegated.

Charters typically granted companies authority to recruit and transport settlers to designated territories, establish initial governance structures pending formal integration, and negotiate treaties and agreements with neighboring entities. Companies could levy certain taxes and fees within their territories, issue bonds and other financial instruments backed by federal guarantees, and grant land titles and commercial concessions. Security powers included the authority to maintain forces for territorial protection, while diplomatic functions allowed companies to exercise temporary foreign affairs powers within defined parameters.

These broad powers made settlement companies quasi-governmental entities during the active colonization phase. The charters also imposed obligations including regular reporting to the Council of State, adherence to federal labor and environmental standards (as they existed and developed), and eventual transfer of governmental functions to permanent regional authorities.

Federal oversight

The Infrastructure Development Bank (IDB), established in 1685 AN as part of the New Prosperity Plan, served as the primary federal oversight body for settlement companies. The IDB managed the flow of appropriated funds, guaranteed company bond issuances, monitored financial performance, and coordinated activities across multiple companies. This centralized oversight aimed to ensure efficient resource allocation and prevent duplication of efforts.

The Department of the Treasury maintained fiscal oversight, tracking appropriations and expenditures while managing the complex web of guarantees that supported settlement company financing. The Wechua Planning Commission provided technical assistance on planning and development standards, drawing on its experience with the Five-Year Plans.

Despite these oversight mechanisms, the rapid pace of expansion and the geographic dispersion of activities created information gaps that would later complicate the wind-down of company operations. The variance between appropriated and expended funds reflected not only successful cost management but also incomplete project execution, deferred expenditures, and accounting complexities that proved difficult to resolve.

Companies

New Luthoria Settlement Company

| Native name | Compañía de Colonización de Nueva Luthoria |

|---|---|

| Former type | Chartered settlement company |

| Fate | Assets transferred to New Luthoria and Islas de la Libertad regional governments |

| Defunct | 1700 AN |

| Area served | Skerry Isles, Islas de la Libertad, Orange Sea region |

| Products | Settlement, infrastructure, maritime services |

| Owner(s) | Federal government (65%), private investors (35%) |

| Parent | Infrastructure Development Bank |

The New Luthoria Settlement Company was chartered in 1686 AN to execute the Orange Sea Expansion, establishing New Alexandrian sovereignty over the Skerry Isles, the Islas de la Libertad, and surrounding waters. The company received appropriations of NAX€212 billion, of which NAX€98 billion was expended on settlement activities, leaving a variance of NAX€114 billion.

The company's mandate encompassed two distinct but geographically proximate territories. The Skerry Isles presented unique challenges for settlement. The archipelago's remote location, limited agricultural potential, and harsh maritime climate required substantial investment in port facilities, fishing infrastructure, and housing suitable for the environment. The company focused on developing Pharos City as the regional capital and primary port, constructing harbor facilities capable of supporting both commercial shipping and the Federal Forces' naval operations in the Orange Sea.

The Islas de la Libertad, while sharing maritime characteristics with the Skerry Isles, offered somewhat more favorable conditions for agricultural development and a more temperate climate. The company established port facilities and fishing communities across the archipelago, while also developing plantation agriculture where conditions permitted. The islands' strategic position along major shipping routes made them valuable for both commercial and military purposes, with company investment in harbor infrastructure serving dual civilian and naval functions.

Settlement across both territories proceeded primarily through the recruitment of fishing communities, maritime workers, and military personnel willing to relocate to the islands. The company offered generous land grants, housing subsidies, and guaranteed employment contracts to attract settlers. Coordination between the two territorial operations allowed the company to achieve economies of scale in logistics and administration, with supply vessels and personnel moving between the Skerry Isles and Islas de la Libertad as operational needs dictated.

The two territories followed different paths to regional status. The Federal Constituent Assembly approved New Luthoria as a Region of the Federation in 1687 AN, establishing permanent governmental structures in the Skerry Isles while settlement activities continued. The Islas de la Libertad remained under direct company administration for several additional years as its settler population grew and institutional capacity developed. In 1691 AN, the Cortes Federales approved Islas de la Libertad as a separate Region, recognizing that the archipelago's distinct geography, economy, and growing population warranted its own regional government rather than incorporation into New Luthoria.

The company was dissolved in 1700 AN, with its assets including port facilities, land holdings, and ongoing infrastructure projects divided between the New Luthoria and Islas de la Libertad regional governments. Residual financial obligations, primarily bonds issued to finance port construction, were absorbed by the Infrastructure Development Bank.

Caputian Resettlement Authority

| Native name | Autoridad de Reasentamiento Caputiana |

|---|---|

| Former type | Chartered settlement company |

| Fate | Assets transferred to Isles of Caputia regional government |

| Defunct | 1698 AN |

| Area served | Captive Sea, Caputian archipelago |

| Products | Settlement, refugee resettlement, infrastructure |

| Owner(s) | Federal government (60%), private investors (40%) |

| Parent | Infrastructure Development Bank |

The Caputian Resettlement Authority was chartered in 1686 AN to execute the Captive Sea Expansion and facilitate the resettlement of Caputian diaspora populations. The company received appropriations of NAX€211 billion, with NAX€104 billion expended, leaving a variance of NAX€107 billion.

Unlike other settlement companies focused primarily on recruiting new settlers, the Caputian Resettlement Authority served a distinct humanitarian mission. Following the Alexandrian flu and the collapse of the original Caputia, substantial diaspora populations had scattered across Micras. The Authority worked to locate, recruit, and resettle these populations in the Isles of Caputia, providing transportation, housing assistance, and economic integration support.

The Authority established its headquarters in Gotfriedplatz, which developed into the regional capital. Major construction projects included port facilities at Port Tablot, Port Karsten, and Velez, along with housing developments designed to accommodate the influx of resettled populations. The company also invested heavily in agricultural development, establishing farming communities across the islands' arable lands.

The Isles of Caputia was formally integrated as a Region in 1687 AN. The Caputian Resettlement Authority was among the first companies to complete its primary mission, continuing operations through 1698 AN to manage ongoing resettlement programs and infrastructure development before transferring assets to the regional government.

Lyrican Settlement Company

| Native name | Compagnie de Colonisation Lyricaine |

|---|---|

| Former type | Chartered settlement company |

| Fate | Assets divided between North Lyrica and South Lyrica regional governments |

| Defunct | 1702 AN |

| Area served | Lyrica (core island territories) |

| Products | Settlement, agriculture, timber, mining |

| Owner(s) | Federal government (55%), private investors (45%) |

| Parent | Infrastructure Development Bank |

The Lyrican Settlement Company was chartered in 1687 AN to execute the Lyrican Expansion, the largest single territorial expansion in the New Prosperity Plan. The company received appropriations of NAX€583 billion, the highest of any settlement company, with NAX€176 billion expended and a variance of NAX€407 billion.

Lyrica, a large island in the waters between Keltia and the Skerry Isles, offered substantial agricultural potential along with timber and mineral resources. The island's size and resources justified the largest appropriation of any settlement company, though the magnitude of the variance between appropriated and expended funds would later draw scrutiny. The company maintained dual headquarters: administrative offices in Beaufort (which became the capital of North Lyrica) and operational headquarters in Lausanne (which became the capital of South Lyrica).

Settlement focused on establishing agricultural communities in the fertile southern regions and resource extraction operations in the more rugged north. The company recruited settlers from across the Federation, with particularly strong recruitment from Alduria and the Wechua Nation. Major infrastructure projects included road networks connecting the island's major settlements, port facilities at Beaufort, Lausanne, and Benavides, and the initial development of what would become the island's timber industry.

Both North Lyrica and South Lyrica were integrated as separate Regions in 1687 AN, reflecting geographic and economic differences that warranted distinct administrative structures. The company operated across both territories until 1702 AN, when its assets were divided between the two regional governments. This division process proved complex, with disputes over asset valuation and liability allocation requiring arbitration by the Infrastructure Development Bank.

Palmas Settlement & Construction Company

| Native name | Compañía de Colonización y Construcción de Palmas |

|---|---|

| Former type | Chartered settlement company |

| Fate | Assets transferred to North Lyrica regional government |

| Defunct | 1703 AN |

| Area served | Talamthom region (northern and eastern North Lyrica) |

| Products | Settlement, construction, infrastructure |

| Owner(s) | Federal government (60%), private investors (40%) |

| Parent | Infrastructure Development Bank |

The Palmas Settlement & Construction Company was chartered in 1688 AN to execute the Talamthom Expansion, extending New Alexandrian sovereignty into the northern and eastern portions of North Lyrica beyond the territories initially settled by the Lyrican Settlement Company. The company received appropriations of NAX€391 billion, with NAX€98 billion expended and a variance of NAX€293 billion.

Talamthom presented challenging terrain, with numerous islands and limited agricultural land. The company focused on resource extraction, particularly timber and minerals, rather than large-scale agricultural settlement. Construction of access roads and processing facilities consumed a significant portion of expenditures, while the smaller settler population required less investment in housing and social infrastructure compared to other expansion territories.

The company maintained close coordination with the Lyrican Settlement Company, sharing logistics networks and occasionally collaborating on infrastructure projects that crossed their respective territorial mandates. This cooperation was formalized through inter-company agreements facilitated by the Infrastructure Development Bank.

Upon dissolution in 1703 AN, the company's assets were transferred to the North Lyrica regional government. The relatively underdeveloped state of Talamthom at the time of transfer contributed to ongoing infrastructure deficits that regional authorities would address over subsequent decades.

Wechua-Santanderian East Keltian Company

| Native name | Compañía Wechua-Santanderiana de Keltia Oriental |

|---|---|

| Former type | Chartered settlement company |

| Fate | Assets distributed to Santander and Wechua Nation regional governments; residual obligations absorbed by Federal Special Funds |

| Defunct | 1705 AN |

| Area served | Eastern Keltia |

| Products | Settlement, mining, agriculture, transportation |

| Owner(s) | Federal government (70%), private investors (30%) |

| Parent | Infrastructure Development Bank |

The Wechua-Santanderian East Keltian Company was chartered in 1689 AN to execute the first phase of Keltian expansion, extending New Alexandrian influence into eastern Keltia. The company received appropriations of NAX€248 billion, with only NAX€20 billion expended by the time of dissolution, leaving a variance of NAX€228 billion, the highest proportional variance of any settlement company.

The company's mandate was the most ambitious of the settlement companies, aiming to establish New Alexandrian presence across vast stretches of eastern Keltia. However, the sheer scale of the territory, combined with logistical challenges and competing priorities elsewhere in the New Prosperity Plan, resulted in limited progress during the company's operational period. Most expenditures focused on establishing initial outposts, conducting surveys, and building transportation links to connect potential settlement areas with existing Federation infrastructure.

The company's headquarters in Wechuahuasi reflected the Wechua Nation's and Santander's geographic proximity to eastern Keltia. The company drew heavily on Wechua planning expertise and Santanderian commercial networks, with its board of directors including representatives from both regions' governments and business communities.

The Wechua-Santanderian East Keltian Company was the last of the major settlement companies to be dissolved, remaining operational until 1705 AN. Its extended operational period reflected both the incomplete state of its settlement mission and the complexity of winding down its extensive territorial claims. Physical assets, primarily survey equipment, outpost facilities, and transportation infrastructure, were distributed between the Santander and Wechua Nation regional governments based on geographic proximity. Residual financial obligations were absorbed by the Federal Special Funds, particularly the Special National Defense Fund, justified by the strategic importance of eastern Keltian positions.

Financial structure

The settlement companies were capitalized through a combination of federal appropriations, private equity investment, and debt financing. Federal appropriations, channeled through the Infrastructure Development Bank, provided the foundation of each company's capital base. Private investors, including nobles, entrepreneurs, and institutional investors, contributed additional capital in exchange for equity stakes typically ranging from 30% to 45%.

| Company | Chartered | Appropriated | Expended | Variance | Federal Stake |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Luthoria Settlement Company | 1686 AN | NAX€212 billion | NAX€98 billion | NAX€114 billion | 65% |

| Caputian Resettlement Authority | 1686 AN | NAX€211 billion | NAX€104 billion | NAX€107 billion | 60% |

| Lyrican Settlement Company | 1687 AN | NAX€583 billion | NAX€176 billion | NAX€407 billion | 55% |

| Palmas Settlement & Construction Company | 1688 AN | NAX€391 billion | NAX€98 billion | NAX€293 billion | 60% |

| Wechua-Santanderian East Keltian Company | 1689 AN | NAX€248 billion | NAX€20 billion | NAX€228 billion | 70% |

| Total | – | NAX€1.645 trillion | NAX€496 billion | NAX€1.149 trillion | – |

The variance between appropriated and expended funds, totaling NAX€1.149 trillion across all companies, reflected multiple factors. Some funds were legitimately returned to the federal treasury upon project completion or cost savings. Other portions remained as contingent liabilities, were rolled into Infrastructure Development Bank obligations, or funded cost overruns on other New Prosperity Plan projects. The accounting for these variances proved complex and would influence the Federation's fiscal position for decades.

Bond financing

Settlement companies supplemented their equity capital through bond issuances, primarily through the New Prosperity Bonds program administered by the Infrastructure Development Bank. These bonds carried maturities of 10 to 15 years with interest rates of 8-10%, attractive terms backed by federal guarantees that drew substantial domestic and international investment.

The IDB underwrote company bond issuances, providing explicit federal guarantees that made the instruments essentially equivalent to sovereign debt. This arrangement allowed companies to borrow at favorable rates while transferring ultimate credit risk to the federal government. The global scope of bond sales, including placements in Raspur Pact countries, demonstrated international confidence in the New Alexandrian expansion program.

Settlement company bonds were tradeable on the Cárdenas Stock Exchange, providing liquidity for investors. The IDB also operated an eCommerce platform facilitating foreign investment, in partnership with the Import-Export Bank. By the early 1690s, combined settlement company and IDB bond sales had reached NAX€240 billion, with approximately NAX€112 billion from domestic sources.

Private investment incentives

Private investors in settlement companies received various incentives beyond simple equity returns. Investors received preferential access to land in newly settled territories, often at nominal prices, along with exclusive or preferential rights to conduct specific commercial activities such as mining, timber extraction, and trading within company territories. Tax advantages reduced the burden on income derived from settlement company investments, while significant investors could obtain positions in local governance structures or advisory roles. Early access to commercial opportunities in developing territories provided first-mover advantages that could translate into lasting economic dominance in newly settled regions.

These incentives attracted investment from across the Federation and from allied nations. Noble families, merchant houses, and emerging industrialists saw settlement company investment as a path to economic advancement and political influence in the expanding Federation.

Guarantee cascade

The settlement company financing structure created a layered system of guarantees that would later prove problematic. The federal government explicitly guaranteed IDB bonds, which in turn guaranteed settlement company bonds. Settlement companies guaranteed loans to private contractors engaged in colonization activities. Regional development banks, established to support local infrastructure, provided additional guarantees for projects within their jurisdictions.

This cascade created substantial implicit federal liabilities that did not appear on official government balance sheets. When projects succeeded, these guarantees remained inactive. When projects encountered difficulties, however, the guarantee structure could concentrate losses at the federal level. The full extent of these contingent obligations was not systematically tracked during the active settlement period, complicating later efforts to assess the true fiscal cost of territorial expansion.

Operations

Settler recruitment

Settlement companies employed comprehensive campaigns to attract settlers willing to relocate to new territories. Recruitment efforts targeted diaspora communities, particularly for the Caputian Resettlement Authority, which recruited scattered populations from Alexandria, Caputia, and elsewhere. Agricultural workers seeking land ownership opportunities unavailable in established regions formed a major recruitment pool, as did skilled tradespeople such as carpenters, masons, and blacksmiths essential for building new communities. Maritime workers including fishermen, sailors, and port workers were recruited for coastal settlements, while military veterans were offered land grants in exchange for providing security in frontier territories.

Recruitment incentives typically included transportation subsidies, land grants ranging from small homesteads to larger estates for substantial investors, housing assistance, guaranteed employment contracts, and provisions for the first year of settlement. Companies established recruitment offices in major Federation cities and, for some companies, in allied nations.

Infrastructure development

A major portion of settlement company expenditures went toward infrastructure development. Ports and harbors were essential for maritime territories and for connecting settlements to Federation trade networks. Roads and bridges provided transportation links connecting new settlements to each other and to established regions. Housing construction accommodated settler populations, while public buildings provided space for government offices, schools, clinics, and other civic facilities. Utilities including water supply, sanitation, and (where feasible) connection to the developing national electrical grid rounded out the infrastructure programs.

Companies frequently engaged the National Construction Company, a government-owned contractor, or private contractors such as ESB Construction and Parap Construction and Engineering for construction work. Many projects were executed through public-private partnerships that granted contractors ongoing operational rights, such as toll collection, in exchange for construction investment. This approach reduced immediate capital requirements while creating long-term revenue-sharing obligations.

Governance establishment

Settlement companies exercised temporary governmental authority in their territories pending formal integration as Regions of the Federation. This authority encompassed administrative functions such as tax collection, record-keeping, and land registration; judicial functions including basic dispute resolution and enforcement of company regulations; security responsibilities for maintaining order; and diplomatic functions for negotiating with neighboring entities as authorized by company charters.

Each company received a delegation from Cárdenas comprising experts in public administration, legal scholars versed in federal law, and diplomatic personnel authorized to represent New Alexandrian interests. These delegations served as the institutional link between frontier territories and the central government, ensuring that company governance adhered to federal standards and that the transition to permanent regional government would proceed smoothly. The delegations also included surveyors, engineers, and economic advisors who assessed territorial resources and planned infrastructure development in coordination with company leadership.

Security in newly settled territories relied on a combination of forces. The Federal Forces of Nouvelle Alexandrie, still in the early stages of their institutional development during the late 1680s and 1690s, provided garrison troops and naval patrols where strategic considerations warranted direct military presence. However, the rapid pace of expansion across multiple continents stretched federal military capacity. To supplement these forces, settlement companies contracted extensively with the ESB Group, whose mercenary units provided security services ranging from frontier patrol and convoy protection to the suppression of banditry. ESB personnel operated under company authority but coordinated with Federal Forces commanders to ensure unified security operations across territorial boundaries.

As settler populations grew and territorial governance matured, companies gradually transferred functions to permanent governmental structures. This transition was formalized through organic laws approved by the Federal Constituent Assembly or Cortes Federales that established each territory as a Region of the Federation with its own regional government. The Cárdenas delegations typically formed the nucleus of the new regional administrations, with experienced personnel transitioning from company service to permanent government positions.

Dissolution and legacy

The settlement companies were never intended to be permanent institutions. Their charters anticipated eventual dissolution once primary settlement objectives were achieved and permanent regional governments were established. The wind-down process, which occurred between 1698 AN and 1705 AN, involved asset transfers of physical property including land, buildings, infrastructure, and equipment to regional governments; liability resolution through satisfaction, transfer to regional governments, or absorption by the Infrastructure Development Bank and Federal Special Funds; equity settlement providing private investors with final distributions in the form of land, concession rights, or cash; and personnel transitions moving company employees to regional government positions, private employment, or retirement.

The complexity of this process varied by company. The Caputian Resettlement Authority, with its relatively contained geographic scope and completed humanitarian mission, wound down relatively smoothly by 1698 AN. The Wechua-Santanderian East Keltian Company, with its incomplete settlement program and extensive territorial claims, required extended operations through 1705 AN and left significant residual obligations.

Financial legacy

The settlement companies left a complex financial legacy that would influence Federation fiscal policy for decades. The NAX€1.149 trillion variance between appropriated and expended funds, representing nearly 70% of total allocations, required careful disposition and generated substantial controversy during the wind-down period.

Disposition of variance funds

The variance between appropriated and expended funds resulted from multiple factors, each accounting for a portion of the unexpended balance. Approximately NAX€385 billion was legitimately returned to the federal treasury as unspent appropriations. Settlement activities in several territories proceeded more efficiently than projected, while the incomplete mandate of the Wechua-Santanderian East Keltian Company meant that substantial funds allocated for eastern Keltian development were never deployed. The Department of the Treasury received these returns over an extended period as companies wound down operations between 1698 AN and 1705 AN.

A second major category, approximately NAX€285 billion, was redirected to cover cost overruns elsewhere in the New Prosperity Plan. The construction of Cárdenas, the Pan-Euran Highway, and the Pan-Keltian Highway all exceeded initial budget projections, and settlement company surpluses provided a convenient source of supplemental funding. These transfers occurred through the Infrastructure Development Bank, which served as the financial clearinghouse for the entire New Prosperity Plan. While legal under the Plan's enabling legislation, these redirections meant that settlement company appropriations effectively subsidized infrastructure projects far from the territories they were nominally intended to develop.

The Infrastructure Development Bank and Federal Special Funds absorbed approximately NAX€240 billion in settlement company obligations. Outstanding bonds approaching maturity, incomplete project commitments, and guarantee liabilities that materialized when contractors defaulted all required funding beyond direct settlement expenditures. The absorption of these obligations into the Special Funds, particularly the Special National Defense Fund and the Federal Infrastructure Fund, contributed to the apparent size of those reserves while simultaneously reducing their discretionary availability. This accounting treatment allowed the government to present healthy fund balances while obscuring the committed nature of substantial portions.

Contingent liabilities accounted for another NAX€115 billion held in reserve against guarantees that might be called. Settlement companies had guaranteed loans to contractors, development partners, and regional banks financing settlement-related activities. These guarantees created ongoing obligations that could materialize if underlying projects failed. Rather than releasing these reserves when companies dissolved, the funds were transferred to the Federal Special Funds as ongoing contingent reserves. Some of these guarantees were eventually called, while others expired without incident, but the uncertainty surrounding their disposition complicated fiscal planning for years.

Land and asset transfers created valuation discrepancies totaling approximately NAX€80 billion. Assets were carried on company books at appropriation-era valuations, but when transferred to regional governments, assessments often revealed lower market values. Undeveloped land in remote territories, partially completed infrastructure, and equipment depreciated during the settlement period all transferred at values below their original allocation. The difference remained as a paper loss absorbed across federal accounts.

Graft, waste, and accountability

Audits conducted by the Department of the Treasury during the wind-down period between 1698 AN and 1705 AN, revealed that approximately NAX€44 billion had been lost to graft, waste, and accounting irregularities. Fraudulent contractor invoices, inflated land purchase prices benefiting connected sellers, and outright embezzlement by company officials accounted for the bulk of identified losses. The Lyrican Settlement Company proved particularly problematic, with Treasury investigators documenting systematic overbilling by timber contractors and land speculation schemes involving company directors.

The federal government responded with a series of sanctions and prosecutions. Fourteen company officials across three settlement companies faced criminal charges, with seven resulting in convictions for fraud or embezzlement. Thirty-two contracting firms were permanently barred from federal contracts, while another sixty-seven faced temporary suspensions. The Palmas Settlement & Construction Company was placed under direct Treasury supervision for its final two years of operation after auditors discovered that regional managers had awarded contracts to family members at inflated prices.

These accountability measures, while significant, recovered only a fraction of misappropriated funds. Critics argued that the decentralized structure of settlement company operations, combined with the rapid pace of expansion across multiple continents, had created conditions conducive to corruption. The geographic distance between frontier operations and oversight bodies in Cárdenas, the pressure to demonstrate quick results, and the substantial sums flowing through relatively new institutions all contributed to an environment where accountability mechanisms struggled to keep pace with expenditure.

Long-term resolution

Following the Societe General d'Alduria model, some settlement company land holdings continued to be managed "in trust" rather than fully transferred to regional governments, creating ongoing administrative and legal complexities. This practice was particularly extensive in North Lyrica and South Lyrica. These trust arrangements persisted for decades in some cases, with the Infrastructure Development Bank serving as trustee for properties that defied easy categorization or that carried unresolved title disputes.

The resolution of these legacy issues occurred gradually over the following decades, facilitated by the Alexandrium Miracle revenues that began flowing in the 1730s. The Federal Sovereign Wealth Fund, established in 1731 AN, provided fiscal resources that enabled the final resolution of settlement company obligations while maintaining the Federation's overall fiscal stability. By 1740 AN, the last major settlement company liabilities had been cleared, though scattered trust properties and dormant guarantee accounts persisted in federal records well into the 1750s.

Territorial impact

Despite the financial complexities, the settlement companies achieved their primary objective: the rapid expansion of Nouvelle Alexandrie from its founding territories of Alduria and the Wechua Nation to a continental power spanning Eura, Keltia, and the Skerry Isles. By 1693 AN, when the Federation was renamed from Alduria-Wechua to Nouvelle Alexandrie, the settlement companies had facilitated the integration of Santander and Valencia in 1686 AN; the Isles of Caputia, North Lyrica, South Lyrica, and New Luthoria in 1687 AN; and Islas de la Libertad in 1691 AN; with ongoing expansion into Talamthom (northeastern Lyrica) and eastern Keltia continuing through the 1690s.

This territorial expansion transformed Nouvelle Alexandrie into one of Micras's major powers, with strategic positions across multiple continents and control over vital shipping routes. The infrastructure established by the settlement companies, while requiring subsequent investment and maintenance, provided the foundation for the Federation's economic development and military capabilities.

Criticism

The settlement companies, while successful in their primary objectives, faced various criticisms during their operation and in subsequent historical assessment. The complex web of appropriations, expenditures, guarantees, and inter-company arrangements made it difficult to assess the true cost of territorial expansion. Critics argued that this financial opacity obscured inefficiencies and facilitated the accumulation of hidden liabilities that would burden federal finances for decades.

Questions of equity also surrounded the settlement program. Some observers noted that well-connected investors received disproportionate benefits through favorable land grants, commercial concessions, and governance positions. The concentration of these benefits among economic elites contrasted with the program's stated goals of broad-based national development and opportunity.

Resource extraction activities, particularly in Lyrica, proceeded with limited environmental oversight. Timber harvesting and mining operations established patterns of resource use that would later contribute to environmental challenges, including elements of the North Lyrica logging scandal of 1749 AN. While the territories settled were officially designated as the Green (unclaimed and unowned), some critics noted that the rapid pace of settlement gave limited attention to any existing populations or pre-existing claims.

The significant variances between appropriated and expended funds raised additional concerns about company effectiveness. The Wechua-Santanderian East Keltian Company expended only NAX€20 billion of its NAX€248 billion appropriation, suggesting that some companies failed to fully execute their settlement mandates despite receiving substantial resources. Whether these variances reflected prudent cost management, inadequate planning, or simple failure to deliver on ambitious promises remained subjects of debate among economists and historians.

See also

- New Prosperity Plan

- Financial history of Nouvelle Alexandrie

- Federal Special Funds of Nouvelle Alexandrie

- Infrastructure Development Bank of Nouvelle Alexandrie

- Societe General d'Alduria

- Settlement companies

- Administrative divisions of Nouvelle Alexandrie

- North Lyrica logging scandal

- The Green