Normandie

| L'Ordre des Lacs sacrés du chef du duché de Normandie The Order of the Holy Lakes in right of the Duchy of Normandie | |||

| |||

| Motto: | |||

| Anthem: | |||

| |||

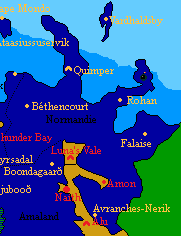

| Map versions | |||

| Capital | Quimper | ||

| Largest city | Béthencourt, Rohan, Falaise, Caustren | ||

| Official language(s) | Norman, Alexandrian, Hurmu Norse | ||

| Official religion(s) | Reformed Norman Church | ||

| Demonym | Norman(s) | ||

| - Adjective | Norman | ||

| Government | Proposed realm of the Order of the Holy Lakes | ||

| - Duke | Theodoric van Orton | ||

| - Legislature | |||

| Establishment | 1744 AN | ||

| Area | |||

| Population | 13,533,787 (1748) | ||

| Currency | Crown (HUK) | ||

| Calendar | |||

| Time zone(s) | CMT+3 | ||

| Mains electricity | |||

| Driving side | left | ||

| Track gauge | |||

| National website | |||

| National forum | |||

| National animal | |||

| National food | |||

| National drink | |||

| National tree | |||

| Abbreviation | TBD | ||

Normandie (also spelt Normandy; in Hurmu Norse: Noorðmannaland; see also that article) is one of the List of realms of the Order of the Holy Lakes of the Order of the Holy Lakes located on the west coast of Keltia, in the Normandie region, immediately north of Amaland and east of the Hexarchy. Normandie was admitted to the Order of the Holy Lakes on 6.I.1745.

Known for its rugged coastline, harsh winters, and historically rich settlements, Normandie traces its origins to the era of Storish rule, when it served as a distant but culturally distinct province. Following a period of foreign domination by the Hexarchy and administration under the Autonomous Region of Lysstyrer, the region fell into disorder during the Vanic incursions, which brought widespread devastation and spiritual desecration.

After years of unrest, the duchy was liberated in 1744 AN through a coordinated uprising led by local militias and clergy aligned with the Reformed Church of Normandie, a fiercely anti-Vanic religious institution that now serves as a cornerstone of national identity and governance. Today, Normandie is ruled by Duke Thedoric van "Randy" Orton, whose reign emphasizes religious purity, anti-Vanicism, agrarian values, and resistance to foreign cultural influence.

With a population of just shy of 12 million, the duchy's economy is centred on subsistence agriculture, coal mining, and religious tourism. The Norman people are known for their deep spiritual devotion, communal lifestyle, and ancestral connection to the land. Major cities include Quimper (the capital), Béthencourt, and Caustren, each playing a unique role in the duchy's political, industrial, and spiritual life.

Profile

The Grand Duchy of Normandie, historically part of the now-defunct High Realm of Stormark, is a semi-autonomous region known for its strong knightly traditions, cultural conservatism, and medieval heritage. Following the dissolution of Stormark in the mid-18th century, Normandie retained much of its regional identity and institutions, though it has since undergone political, social, and religious transformation under growing Devanic influence from neighboring states, especially Hurmu.

Normandie is located on the western fringe of the Twin Peninsula, facing the Sunset Sea to the west. The landscape consists of fertile plains, low mountainous ridges to the east and south, broad river valleys, and temperate forests. Historically rich in game and natural resources, the region has sustained agricultural and pastoral communities for centuries. Once a core province of Stormark, Normandie played a central role in preserving and promoting chivalric traditions. Together with Port Chloe and the Providence Plantations, it formed the heartland of knightly culture within the High Realm. Formal tournaments, hereditary orders, and codes of knighthood were more strictly observed here than anywhere else in the former realm.

After the collapse of Stormark (c. 1685), the Grand Duchy lost its central governance structure. Regional noble houses maintained limited authority, but over time, Normandie came under external ideological and religious pressure, particularly from Hurmu and other Devanicized polities seeking to dismantle remaining Vanic legacies. Despite the political shifts, Normandie has retained a strong regional identity. Medieval towns with cobblestone streets, fortified walls, and timber-framed houses are common. Though many of these towns have modernized, their historical cores remain intact. Festivals, fairs, and ceremonial parades reflect a cultural continuity that dates back centuries, although participation has declined in recent years.

The Church has seen a resurgence in influence since the Vanic religion was officially outlawed in 1744 under the Devanicization decrees. The pre-Vanic Norman traditions—folk rites, chivalric pageantry, and ancestral customs—have experienced a revival, albeit often in secular or symbolic form. Irreligious or secular residents, however, sometimes face social suspicion, being loosely associated with the former Vanic regime. In the decades following Stormark’s dissolution, Normandie has adopted limited modernization. Infrastructure improvements and trade integration have reshaped many urban centers, while rural areas remain comparatively traditional. Cultural preservation societies, supported by town councils, play a central role in maintaining the region’s historic character.

Although modernization has pushed many knightly institutions into symbolic roles, they remain deeply embedded in the duchy's ceremonial and civic life. The Knightly Lordship is now more a cultural identity than a military one. Normandie remains a symbol of resilience and historical continuity. While its role in continental politics has diminished, its cultural and historical depth continues to attract scholarly interest and tourism. The duchy's identity is marked by a tension between tradition and transformation—between its feudal past and the changing world beyond its borders.

There was a Vanic influence on the culture from the mid-1500s to the late 1600s, but in 1744 the customs and practices of the Vanic religion were banned by the Devanicization policy. The old pre-Vanic Norman culture is now practiced instead. The church also increased its influence in society. This situation puts the irreligious in the position of being Vanic supporters. And also, with the increase of modernization, modern life was adopted and old traditions were involuntarily pushed into the background.

History

Norse Roots and Francian Domination (c. 500–1040)

The origins of Normandie lie in the early Norse settlements that began in the sixth century AN. These settlers established their culture and language across the region, with Old Norse becoming dominant among the common population. In the early 900s, the Kingdom of Franciana, an Old Alexandrian-speaking realm, conquered the territory. Although Francianan rule began the slow Alexandrianization of the region, linguistic and cultural assimilation remained limited. The nobility gradually adopted Alexandrian, while the common folk retained their Norse identity.

The War of the Hand of Hallvarður (1103–1108) and the County of Quercy (1108–1150)

The saga of Normandie's true founding begins with the birth of Rognvald of Valtia in 1040, father of the twins Horik and Hyngwar Rognvaldsson, who were born in 1078. Following their father's assassination in 1100, widely believed to involve the Valtian leadership, the twin brothers were eventually exiled from Valtia. Their notoriety as brutal, cunning mercenaries—commanders of the feared Leopard Legion—preceded them.

In 1103, the Valtian Althing dispatched Jarl Hallvarður Jónsson of the House of Haukdælir to negotiate a political alliance with Franciana, including a proposal for the marriage of Princess Clotilde to a Valtian noble. Rather than accept the offer, King Clovis responded with cruelty and contempt. He had Hallvarður's hands severed and returned them to Valtia with a mocking note. The mutilated envoy was then stoned to death, and his remains desecrated.

This act constituted not merely an insult but an act of war under the diplomatic customs of the time. It was a sacrilegious breach of the sacred trust afforded to emissaries, universally acknowledged as inviolable. The Althing of Valtia declared war, calling upon their maritime chieftains, privateers, and allied warlords to exact retribution.

Valtian-backed corsairs and mercenaries descended upon Franciana, devastating its coastal settlements and trade. Neighboring powers, including Vermandois and Noyon, took advantage of the chaos to launch their own incursions. Franciana, already strained by internal disunity, found itself under siege on all fronts. In desperation, King Clovis turned to a pair of exiled Valtian mercenaries: the Leopard Brothers, Horik and Hyngwar Rognvaldsson.

These brothers—known for their brutality and martial brilliance—had personal grievances against Valtia. In 1104, they agreed to enter Clovis's service. Their Leopard Legion turned the tide of war. At the Battle of Narresroux, they crushed the forces of Vermandois, restoring Franciana’s strategic footing. They were instrumental in purging the land of raiders and bandit hosts.

With Franciana under siege by pirates, mercenaries, and rival kingdoms, Clovis sought unlikely salvation in the Leopard Brothers, who had no allegiance to Valtia and had already begun opportunistic raids in the region. In 1104, the brothers entered Clovis’s service and were rewarded in 1108 with the County of Quercy under the Treaty of Pont l'Évêque. This feudal investiture, marked by the symbolic banner Montjoie, is regarded as the birth of the Duchy of Normandie.

Early Duchy of Normandie (1150–1350)

Horik's son Rollo was born in 1109 and later inherited the county in 1144 following the deaths of Horik (1134) and Hyngwar (1144). Intermarriages with Franciana’s nobility laid the dynastic foundations of the Norman nobility, while the Leopard Brothers' consolidation of power ushered in feudal order. In 1150, Rollo declared himself Duke of Normandie and his duchy independent of Franciana.

With Rollo's succession and stabilization of rule, Normandie grew steadily in influence. The apex of this ascent came with Duke Fulk, the grandson of Rollo, who in 1204 famously conquered the kingdoms of Bosworth and Anglethyr. His rule extended Norman reach across Micras and reinforced their reputation for martial supremacy and cultural sophistication.

Following Fulk's death in 1228, Normandie entered a century-long period of chivalric golden age (1250–1350), defined by the flourishing of knighthood, heraldry, and troubadour culture. The Norman Code of Chivalry, an intricate synthesis of martial, religious, and romantic ideals, was codified and celebrated in tournaments and courtly life.

Fragmentation and Foreign Rule (1350–1543)

Following the end of its golden age, Normandie was increasingly entangled in external conflicts and political instability. From 1452, it was incorporated into the Free Republic and then successively occupied by Varja (1470–1483), Korhal (1487–1490), and Karnali (1490–1516). Governance was inconsistent, and by 1516, Normandie was once again leaderless. Incursions by Durntkinstan beginning in 1529 and expanding in 1534 in the north, and Iridia (1544), in the south, fragmented control.

This was a period of significant decay in Norman sovereignty. The nobility lost cohesion, and ecclesiastical leadership became increasingly influenced by foreign ideologies. It set the stage for a desperate population to welcome Stormark as liberators.

Vanic Subjugation and Cultural Corruption (1543–1685)

In 1543, Stormark entered the scene under the guise of liberators but quickly imposed their ideological and cultural hegemony. Harald Freyjugjöf the Generous Giver, High King of Stormark, was installed as Duke of Normandie. Under Stormark's influence, the Duchy entered an era of Vanicization that deeply corrupted its institutions.

The Église de Normandie, once a Nazarene church rooted in feudal piety, was transformed into a libertine vessel of Vanic cultic influence. The worship of Vanic deities as saints, the installation of female clergy in parity, and ritual nudity during liturgy marked the church's decline into hedonistic spectacle. Most troubling was its theology of sexuality, which elevated polyamory, self-gratification, and public eroticism as sacred acts. Though couched in the language of love and freedom, these practices constituted a profound betrayal of the values upon which the Duchy was founded.

While Stormark praised this era as one of cultural flowering, Norman traditionalists regarded it as a time of humiliation and degradation. The once-honoured Norman Code of Chivalry was distorted into a parody of itself, entangled with Vanic rites and arcane symbolism. Harald Freyjugjöf ruled as both Duke and Pontiff, despite not adhering to the doctrines of the very church he led – a glaring contradiction.

Collapse and the End of Ducal Normandie (1685)

Stormark's collapse in 1685 marked the abrupt end of the Duchy of Normandie as a coherent political and religious entity. No successor government emerged with legitimacy or stability. The Église de Normandie fragmented into regional sects, all repudiating their Vanic past and returning to more orthodox Nazarene traditions. But the damage was lasting: centuries of feudal heritage and chivalric tradition lay buried beneath the rubble of spiritual libertinism and foreign occupation.

Normandie in the Green

- Add context with Amaland and Karnamark... Vanic warfare in the Green

In the late 17th century, during a period of regional instability, Hexarchy forces invaded and annexed the territory. This marked the beginning of a turbulent era. Control was later transferred to the Autonomous Region of Lysstyrer, under which the Normans experienced partial self-governance but limited cultural freedom.

A darker chapter began with the emergence of the Vanic bands, lawless raiding parties whose reign of terror disrupted daily life and eroded local autonomy. For years, these groups committed acts of violence, religious desecration, and economic sabotage across Normandie.

Re-establishment of the Duchy

In 1744 AN, after a sustained campaign of resistance and a series of decisive skirmishes, the Vanic presence was entirely eradicated. This victory is annually commemorated as the Day of Purification, marking a turning point in the duchy’s modern history and solidifying its commitment to self-determination and spiritual unity. In 1745 AN, Normandie was admitted to the Order of the Holy Lakes as a realm. The borders of the duchy were extended by Act of Senate later the same year.

Government and poltics

Today, the Duchy of Normandie is governed as a duchy, as a vassal realm of the Order of the Holy Lakes. At the helm is Duke Theodoric van "Randy" Orton, a charismatic yet austere figure who embodies the ideals of piety, martial valour, and national rebirth.

Political authority is shared with the reformed Norman church, a fiercely anti-Vanic religious institution that commands enormous influence over both civil society and cultural life. The Church dictates education, public morality, and even local policy, serving as the moral backbone of the Norman people. In contrast, an intense wave of secluderization has been observed since the establishment of the state.

The governance structure is hierarchical yet participatory; town councils and regional synods ensure that community voices are heard, albeit under the guiding hand of religious law.

List of rulers

For a family tree of the pre-Storish rulers, see Ragnvald of Valtia.

| Name | Birth | Title | Tenure | Death | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horik Rognvaldsson | 1078 | Count of Quercy | 1108–1134 | 1134 | Twin brother of Hyngwar |

| Hyngwar Rognvaldsson | 1078 | Count of Quercy | 1108–1144 | 1144 | Twin brother of Horik |

| Rollo le Léopard | 1109 | Count of Quercy | 1144–1150 | 1192 | Son of Horik, nephew of Hyngwar; Elevated to Duke after unifying Norman holdings |

| Duke of Normandie | 1150–1192 | ||||

| Fulk | 1152 | Duke of Normandie | 1192–1228 | 1228 | Son of Vilhelm, son of Rollo. Vilhelm predeceased his father. |

| Osmond le Juste | 1185 | Duke of Normandie | 1228–1247 | 1247 | Eldest son of Duke Fulk; known for legal reform and stabilizing chivalric orders. |

| Raoul de Quercy | 1210 | Duke of Normandie | 1247–1269 | 1269 | Son of Osmond; consolidated Norman control over Bosworth. |

| Bertrand I | 1235 | Duke of Normandie | 1269–1293 | 1293 | Nephew of Raoul; claimed ducal title through maternal line and papal support. |

| Arnaut I | 1268 | Duke of Normandie | 1293–1294 | 1294 | Young son of Bertrand I; ruled briefly before dying of illness. |

| Bertrand II | 1242 | Duke of Normandie | 1294–1302 | 1302 | Uncle of Arnaut I; reclaimed title amidst regency collapse. |

| Henri de Béthencourt | 1270 | Duke of Normandie | 1302–1348 | 1348 | Married Bertrand II's granddaughter; brought Béthencourt line into succession. |

| Louis the Protector | 1312 | Duke of Normandie | 1348–1366 | 1366 | Son of Henri; emphasized religious patronage and cathedral expansion. Considered a patron saint of the Norman church, with the epithet, "the protector" (Le Protecteur). |

| Amaury I | 1338 | Duke of Normandie | 1366–1380 | 1380 | Cousin of Louis; succeeded by designation during Louis’s final illness. |

| Gilles | 1359 | Duke of Normandie | 1380–1387 | 1387 | Son of Amaury I; died young in a hunting accident. |

| Thibault | 1326 | Duke of Normandie | 1387–1423 | 1423 | Elder cousin of Gilles; brought stability during times of external threat. |

| Arnaut II | 1400 | Duke of Normandie | 1423–1429 | 1429 | Grandson of Thibault; killed in battle against Varjan forces. |

| Bertrand III | 1403 | Duke of Normandie | 1429–1433 | 1435 | brother of Arnaut II; abdicated due to illness. |

| Henri II | 1408 | Duke of Normandie | 1433–1449 | 1449 | youngest brother of Arnaut and Bertrand; last fully autonomous duke before period of instability. |

| Amaury II | 1430 | Duke of Normandie | 1449–1450 | 1450 | son of Henri II; killed in uprising. |

| Geoffroi the Short-Reigned | 1425 | Duke of Normandie | 1450–1450 | 1450 | Cousin of Amaury II; reigned only six months; son of Jeanne d'Autuncourt – the sister of dukes Arnaut II, Bertrand III and Henri II. |

| Jeanne d'Autuncourt | 1405 | Duchess of Normandie | 1450–1452 | 1470 | Sister of Henri II, Bertrand III, and Arnaut II, mother of Geoffroi; Ruled as duchess before Varjan occupation began. She was also the only female duchess in her own right of Normandie, as all other male descendants were dead at this point. |

| – | – | – | 1452–1543 | – | Interducal era due to warlordism, foreign occupation, and the collapse of internal succession. |

| Harald of Stormark | Duke of Normandie | 1446 | 1543–1685 | 1685 | Duchy of Normandie (Stormark) |

| Esther | Imperial Chieftainness of Normandie | 1638 | 1638–1685 | 1703 | Paternal great grandchild of Harald; title given by Harald at her birth; mainly symbolic. She repudiated the title in 1685. |

| – | – | – | 1685–1744 | – | Interducal era due to warlordism, foreign occupation, etc |

| Theodoric van Orton | Duke of Normandie | 1744– |

Demographics

The vast majority of Normandie's inhabitants identify as Normans, a hardy and devout ethnic group with strong ties to the land and to each other. Their identity is forged through shared struggle, particularly against Vanic incursion, and reinforced through religious and agricultural traditions. The Storish people have largely assimilated, their numbers have dwindled to 17,000. The Karnalis are the second largest ethnic group, living largely in the southern highlands, but recently the Karnalis, who fled Aerla and live in the green lands, have arrived. The Varjans are the fourth largest ethnic group and have a long history in the region, but their numbers have diminished greatly. There are also many Amalanders.

Norman society is deeply conservative, rooted in family structures, communal agriculture, and faith-based values. Hospitality, honor, and devotion to the land are considered sacred duties. While urban centers like Quimper and Béthencourt exhibit some cosmopolitan traits, most of the population lives in rural hamlets, adhering to a lifestyle shaped by the rhythms of the soil and the liturgical calendar. There are considered to be many people who became secularized under the influence of Hurmu in 1744 AN.

Geography and Climate

Normandie lies along a rugged coastal strip, characterized by cold maritime winds, fog-laden cliffs, and dense pine forests that stretch inland to a series of highland plateaus. Winters are long and harsh, with heavy snowfall and freezing temperatures dominating much of the year. The sea, while treacherous, remains vital to the duchy’s fishing communities and modest maritime trade.

The interior is marked by fertile plains and mineral-rich highlands, particularly known for their substantial coal reserves. These geographical features not only sustain agriculture and energy production but also define the social and economic rhythms of Norman life.

Economy

| Currency | Hurmu crown |

|---|---|

| Fiscal Year | 1748 |

| Economic Sectors | Fishing, Mining, Automotive, Services |

The Economy of Normandie is a diversified system combining traditional industries such as fishing and mining with modern sectors including manufacturing, automotive production, and services. Despite its mountainous and cold geography, Normandie has developed into one of the most industrially advanced regions in Micras.

Overview

Normandie’s northern location and harsh winters historically limited large-scale agriculture, leading to an economy long based on fishing, forestry, and mining. In the modern era, the Duchy has embraced industrialization, particularly in the automotive sector, while also developing a strong service industry that supports trade, logistics, finance, and tourism.

Primary sector

- Agriculture: Due to the climate, agriculture is limited to hardy crops such as barley and rye. Animal husbandry, particularly sheep and goat farming, remains important in rural areas.

- Fishing: Fishing and seafood processing are traditional pillars of the Normand economy, with coastal towns relying heavily on cod, herring, and shellfish exports.

- Mining and Forestry: Mountainous terrain provides iron, copper, and silver deposits, as well as timber resources for both domestic use and export.

Secondary sector

- Automotive industry: The cornerstone of modern industrial development, the automotive sector is led by three major companies: Petoya, Hektad, and CAN.

- Shipbuilding and heavy industry: With a strong naval tradition, Normandie continues to produce ships, engines, and industrial machinery.

- Defense production: Automotive technologies are also applied to the manufacture of armored vehicles and winter-adapted transport.

Tertiary sector

- Finance and trade: Normandie’s service sector has grown rapidly, with banking and insurance firms concentrated in major cities.

- Tourism: Despite its cold climate, mountain resorts and coastal landscapes attract visitors. Winter sports and cultural festivals contribute significantly to local economies.

- Logistics and maritime services: Given its geography, Normandie is a hub for shipping and transoceanic trade routes. Ports serve both as fishing harbors and export centers for automobiles and industrial goods.

Economic challenges

Normandie’s reliance on imported agricultural goods makes it vulnerable to supply disruptions. At the same time, environmental pressures from mining and industrialization pose risks to its natural ecosystems. Nevertheless, strong exports in the automotive and service sectors continue to balance these vulnerabilities.