Urchagin

The Urchagin is an initiatory camp attended by Kalgachi youths at around the age of twelve years, at the conclusion of their primary education. It was established by the Pedagogue General's Office of the Directorate of Education and Outreach to infuse moral rigour into those who are too young to have gained it through direct experience of Kalgachia's foundational struggle, such that they understand the nature and purpose of their Kalgachi homeland and are instinctively inclined to defend its name and legacy during their lifetimes, regardless of the condition of the Kalgachi state or the allure of alternatives.

Participation in the Urchagin is voluntary, although many Kalgachi workplaces require it as a condition of employment and the deeper strata of Kalgachi society will readily shun those who have not undergone it.

Development

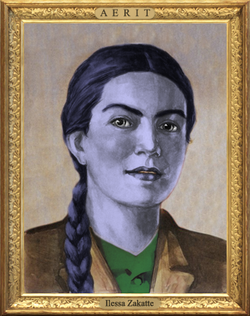

The Urchagin was formulated in 153 Anno Libertatis by Ilessa Aerit, the first Pedagogue General of Kalgachia. Aerit's thesis was that as Kalgachia's founding generation died out, the struggle to establish their homeland would be relegated to the dry and indigestible realm of historical record; that is to say the visceral memory of shared hardship and common cause which motivated Kalgachia's founders to preserve a kernel of the Garden would be lost among their children who would take their inherited culture and liberties for granted, a state of generational complacency from which they could be manipulated to surrender their national self-determination in the face of the very same degenerate forces their parents had fought so hard to survive, escape and resist throughout the history of Minarboria. If the youth of Kalgachia had no profound and personalised reference to Kalgachia's existential imperative, Aerit held, one must be created for them.

Aerit held that the optimum ratio of intelligence and neuroplasticity - that is, the point at which a message could be absorbed across the full spectrum of the subject's conscousness - lay in the years preceding and beginning adolescence. This had long since been discovered and exploited by the Jingdaoese, whose Young Wandering Society would become one of the primary inspirations for Aerit's project. Even if the experience of this adolescent conditioning were to be later opposed by indoctrination of similar or ever greater fullity across the emotive-rational spectrum, Aerit realised that the natural sclerosis of the brain in adulthood would prevent the new conditioning from overlaying or displacing the formative experiences absorbed in early adolescence.

The resulting system, named the 'Urchagin' after a Mishalanski mercenary who supervised the first intake, was implemented by the Directorate of Education and Outreach in a standardised form across Kalgachia. While broadly supported and popular with Kalgachi families (especially those of mongrel ethnicity), the Urchagin system has drawn criticism from elements of the Troglodyti as "a vector for the virulent retransmission of post-traumatic archonic fixation" and more notably from the Salvator of Ketherism, Lord Toastypops, for the barbarism of its initial stages.

Toastypops' objections, carrying a theological weight amplified by the Church of Kalgachia, resulted in a series of reforms in 187 AL whereby the Urchagin programme switched from compulsory to voluntary admission and reduced the mental breaking of children whose conduct did not warrant it. This did result in a slight disdain for "post-Toastypops" Urchagin graduates by their older peers who in turn were considered more robust of spirit by wider society for having undergone the Urchagin "when it was hard", although the variation in quality has been consistently exaggerated.

The Urchagin was further reformed in 226 AL to focus on the more persistent characteristics of Kalgachia's near abroad as opposed to those of specific regimes, and to allow participants a longer period of decompression and mutual bonding before re-introduction with their families.

Urchagin graduates of all periods have been proven to perform better in Kalgachi society than those who have not undergone the programme at all. Like other exercises in secular character-building such as Arithmedarts, its popularity remains undiminished despite the continued scepticism of the clergy and the modularity of its methods has led to its imitation by neighbouring states.

Format

The Urchagin lasts three weeks, totalling fifteen days per the Kalgachi Calendar. Each week, lasting five days each, is run on a different theme representing a portion of Minarborian and Kalgachi history.

Yoke Week

Yoke Week begins with the confiscation of all personal possessions including clothes, which are replaced with ill-fitting overalls. Children are lodged in unheated dormitory huts with coarse woolen bedsheets (too thin in winter, too hot in summer) and no water supply. Access to an ablution hut for hygiene and bodily functions is permitted once per day, with severe penalties attending upon anyone who cannot maintain bladder or bowel control outside of this time - meals being limited to a breakfast of gruel and a dinner of offal with a water ration of two mugfuls a day, avoiding such accidents is easier than might be expected. Sleep is limited to four hours a night.

The camp guards are verbally abusive individuals dressed in military uniform who subject the children to a regime of hard labour such as rock breaking or stripping bark from logs. Slacking or insubordination are met with punishments such as dousing with runny mud or denial of food, which are often administered collectively and sometimes for no reason at all. Guards may manhandle children but are not permitted to administer corporal punishment - however they can and do identify children of submissive and morally weak character to assist them in running the camp. Children who agree to provide this service are granted special privileges including their own more comfortable dormitory and unlike the guards themselves, they are allowed to perform corporal punishment against their erstwhile peers - often being provided with sticks and whips for the purpose although the practice is moderated by the guards' supervision lest it escalate toward permanent disfigurement or a threat to life.

After approximately two days, the camp is suddenly attacked by a hooded mob armed with crowbars and sledgehammers who drive the guards away and begin to smash up the buildings; doors are ripped off their hinges, furrniture is smashed and windows are shattered. After an hour, the attackers - whose only utterance aside from their maniacal laughter is the tuneful phrase "bored now!" - flee the camp at the sight of another group, who arrive dressed in rainbow coloured tunics.

These colourful characters assume the role of the old guards and institute their own regime. Breakfast is changed from gruel to a thin nettle soup, dinner is changed from offal to crushed insect matter and hard labour is replaced with equally-exhausting "enlightenment sessions" - these mandate total submission to the licentious teachings of an invisible, culturally alien élite whose assorted vices are promoted as a superior mode of existence with absolute entitlement to displace the children's pre-existing family, ethnic or civil identity along with any sense of collective agency. Children are forced to identify themselves with the mark of original sin for their ancestors' role in supposed past "atrocities", encouraged to feel shame for all aspects of their "toxic" native culture and to celebrate its fragmentation and ultimate eradication in the name of "diversity". The smallest expressions of quirk or custom learned prior to the enlightenment sessions, or any attempts to communicate beyond the level of the atomised individual, are punished by "privilege checks" where offenders are ritually shamed for their "hate" and "supremacism". Those showing anything less than enthusiastic applause for privilege checks are subjected to privilege checks themselves, such rituals invariably taking up the majority of the regime's tenure. As with the first regime, children who are sufficiently compliant are offered the role of informant and ideological enforcer, enjoying in the process an apparent immunity from privilege checks regardless of their own indiscretions.

At random intervals - sometimes more than once per day - the new regime is driven out of the camp by the return of the hooded vandals who once again spend an hour wrecking the place and flee at the sight of new arrivals; either the old guards or the new guards, who re-implement their particular regime in the camp. Each regime change brings new, pettier and more heavily-enforced rules of conduct, often creating double-binds in which there is no possibility of full compliance. By the final day of Yoke Week these rules are being introduced, amended, removed or inverted without even being announced - the punishment regime simply adapts to them and the children are left to figure out the change by themselves.

Before dawn on the final day of the week, the hooded attackers once again assault the camp - but this time they are joined by both contingents of camp guards. The 'labour' guards wake the children with buckets full of water to their beds, the hooded attackers throw firecrackers around and proceed to completely tear apart the dormitories while the 'enlightenment' guards surround the children with ear-splitting screams of verbal abuse. This tumult continues for a period of one hour until the attackers suddenly withdraw to the camp administration hut, dragging with them any child who has collaborated with them during the course of his or her stay. Shortly afterwards, a party of black-clad individuals wearing skull pendants appear and escort the remaining children out of the camp, taking care to assist those who are too mentally broken to move.

Meanwhile in the administration hut, the 'collaborators' are tied to a chair, doused in buckets full of ordure from the camp latrine and left to sit in it while their assailants (working in shifts) overwhelm their senses with firecrackers, banging saucepans, strobe lights and screams of abuse for a period of twenty continuous hours (or until the camp doctor diagnoses a seizure or cardiac anomaly, whichever comes first). At the conclusion of the session they are hauled away and abandoned at the camp gates - almost always in a state of complete delirium or catatonia, incapable of unaided movement or intelligible speech.

March Week

Escape from the Yoke Week camp signals the start of March Week, in which the children are led by their black-clad guides to an open wilderness camp site where they are allowed to rest for two days. At the beginning of the second day they are joined by the broken 'collaborators' who usually require some degree of assistance with walking, feeding and toileting for the remainder of the week. Better rations are served during this time, and those who still have the strength are taught basic foraging and bushcraft skills by the guides.

On the morning of the third day, the camp is packed up and distributed among the children to carry. The guides then lead the children on a three-day march across the wilderness, making camp at nightfall. Although the journey is long, the March Week guides are more supportive than the Yoke Week guards, encouraging the stronger children to assist stragglers and allowing a full eight hours of sleep each night. Between marches and sleeping, the children are kept occupied with the task of making and breaking camp as a therapeutic decompression from the experience of Yoke Week - guides will readily help out to lessen the children's burden of physical work.

Hearth Week

After five days of March Week, the children are subjected to the usual early waking and camp breakfast in preperation for another day's march, only to move for a modest hour or two before arriving at another camp. The guides leave the children at the camp gates where they pass into the care of kindly folk - often but not always of Nezeni ethnicity - dressed in green-hued robes reminiscent of old fashioned Minarborian clergy. This camp, unlike the one seen in Yoke Week, is well-appointed with comfortable bedding in dormitories which are heated to a cosy warmth by wood-fired stoves when the children arrive. Here they are allowed to catch up on sleep and enjoy a warm shower, being roused at a lesiurely hour of the early afternoon for a generous dinner of prime roasted mutton and fried potatoes with an ice cream dessert. The effect of this meal after so many days of hardship inevitably induces a severe post-prandial lethargy, so the children are sent back to their dormitories to sleep it off for a few hours. In the early evening they are summoned to the camp movie house where they are shown one of the more current youth entertainment features circulating in Kalgachi picture halls.

The rest of the week is occupied with loosely-organised entertainment, leisure and outdoor activities which children are free to choose to their own liking, between generous meals of a standard often better than they receive at home.

On the final day of Hearth Week, always a Byeday, the children attend a Church service - held in the open air, weather permitting - whose officiating Credent is specially trained in delivering an entertaining sermon. After the service comes the Badge Ceremony - usually attended by the children's families - where each child is issued the Urchaginka, a badge featuring a sprig of juniper which is engraved with the recipient's name and date of issue. At the conclusion of the Badge Ceremony, the National Anthem of Kalgachia is sung and the children depart home with their families.

Lessons Learned

According to the DEO Pedagogue General's Office, the succession of experiences obtained from the Urchagin programme are intended to teach the following:

Yoke Week

- The futility of collaboration with the oppressor (there is no refuge in submission).

- The equal utility of rhetorical power, kinetic power and chaos to the oppressor.

- The inevitable trajectory of the oppressor's regime toward a totalisation of sadism and venality, regardless of outlying indicators or assurances to the contrary.

- The capricious and ephemeral nature of power structures outside the Garden and the futility of investing in them.

- The challenge of withstanding collective punishment without becoming divided.

March Week

- Removal of the oppressor's influence as a prerequisite to the repair of shattered dignity.

- An appreciation for the natural geography of the homeland.

- Tolerance of poverty and physical hardship as the acceptable price of freedom from the oppressor.

Hearth Week

- An appreciation of the fruit of ancestral achievements.

- Justification of optimism in times of suffering.

Whole Programme

- Identification of personal skills and deficiencies.

- Assessment of peers' reliability.

- Exposure to wider Kalgachi society.

- Lasting friendship bonds forged in conditions of shared hardship and joy, conducive to future social networking and procreation.

- Appreciation of the secular aspects of the Kalgachi birthright, distinct from purely religious elements.

The Urchaginka as Social Credit

The Urchaginka is minted in a gold-tin alloy of the same weight and value as a Half Kalgarrand - its bearer is expected to retain it for life; any sale or transfer constitutes an immediate revocation of the award and subjects the offender to a Lord Lieutenant's Tribunal, something usually reserved for capital crimes. In later life possession of an Urchaginka is generally required for the more important government jobs in Kalgachia, being absolutely essential for entry into the KDF officer corps and any rank of the Prefects.

Although nominally depicting a sprig of juniper within a U-shaped banner, it is popular among the Nezeni to interpret the shape of the Urchaginka as a stylised depiction of the Broodmother, progenitor of their race, flinging open the collective swaddling cloth of her children.

Participants of a given Urchagin often go on to form tight-knit social groups with each other - an important source of professional patronage for Kalgachi citizens who have no connections elsewhere. Marriages between participants of the same Urchagin are common, commencing earlier and lasting longer than the national average (polyamory has also been noted within such groups). Such is the presence of the 'Urchagin bond' in Kalgachi society that it is considered to serve as a secular and physically rootless equivalent of the societal cohesion seen in the parishes of the state church.

Casualties

It is generally impossible for participants to fail the Urchagin - there is no provision to leave partway through except for a severe medical problem. Notably, those few children who succeed in escaping prematurely from the Yoke Week camp are congratulated on the defence of their dignity and allowed to complete the programme on the condition that they participate in the following two phases (by staying at the first March Week campsite until the others have caught up). At all stages except the atomised "enlightenment sessions", the strongest individuals are persistently encouraged to support their weaker peers in tones of acidic condemnation, quiet request or jolly suggestion depending on the week's theme. In this way even the physically and mentally disabled can complete the Urchagin, although the intensity of certain activities means some children are medically forbidden from participating at all. Lapses in such medical precaution, usually in the form of undiagnosed respiratory or cardiac conditions, are responsible for most of the occasional fatalities suffered during the Urchagin. Such fatalities, while uncommon according to the DEO, are regular enough that a protocol exists for an alternative programme of events during Hearth Week which, while no less comforting, entails a toning down of the more jolly activities out of respect for the deceased child(ren) and those who have witnessed their demise. The cancellation of an Urchagin due to a participant's death is never considered - the notorious Oktavyan Urchagin of 154 AL was pursued to its conclusion even when two-thirds of its participants were wiped out by an avalanche during March Week. Survivors of such incidents traditionally hang small a black ribbon from their Urchaginka in memory of their fallen peers. Death at any stage of the Urchagin counts as a posthumous completion.