Community gathering places in Nouvelle Alexandrie

Community gathering places in Nouvelle Alexandrie, sometimes called third places in academic literature, are communal spaces distinct from home and workplace that function as informal meeting places throughout the Federation of Nouvelle Alexandrie. These spaces emerged from the convergence of Wechua ayllu traditions, Alexandrian café society, and Martino plaza culture following the Alduro-Wechua unification of 1685 AN, with additional influences from Wakara communal traditions after Boriquén joined the Federation in 1718 AN.

The phenomenon encompasses approximately 14,800 distinct gathering spaces across the Federation as of 1750 AN. Surveys indicate that 87 percent of the population frequents at least one type of community gathering place regularly, with urban residents averaging 4.3 visits weekly and rural residents 2.8. These spaces operate through municipal management, cooperative structures, and private ownership, generating an estimated NAX€28.7 billion in annual economic activity.

Cultural origins

The tradition of community gathering places in Nouvelle Alexandrie represents a synthesis of distinct cultural practices that converged during the early federation period.

The Wechua contributed the oldest tradition: the ayllu gathering space, where community members assembled for collective decision-making and social hierarchies temporarily dissolved. Chicherías, informal drinking establishments serving chicha from private homes, had operated in Wechua communities for centuries before the federation's formation, their entrances marked by red bags or corn husks tied to bamboo poles. These spaces embodied the principles of ayni (reciprocal assistance) and mink'a (communal work), creating environments where individual and collective needs merged through shared activity and drink.

Alexandrian café culture contributed intellectual and social discourse elements drawn from centuries of public houses serving as forums for political debate, literary discussion, and social mixing. The Alexandrian practice of salon publique emphasized refined conversation and cultural exchange in accessible settings, extending intellectual life beyond elite circles.

Martino plaza traditions brought the concept of the central public square as the heart of community life, where commerce, celebration, worship, and governance intersected in a single physical space. The Martino custom of paseo, the evening stroll through public spaces for social interaction, provided the rhythm and ritual that structured daily community engagement.

This cultural fusion accelerated during the economic disruptions of 1688 AN-1690 AN, when practical necessity drove communities to create shared resources for survival. The blending occurred as mixed neighborhoods sought common ground for cooperation, with each culture contributing elements that enhanced collective resilience. Wechua families opened their chicherías to Alexandrian and Martino neighbors. Alexandrian café owners began serving wira yaku (herbal infusions) alongside coffee. Martino plaza merchants shared stall space with Wechua vendors.

The integration of Boriquén in 1718 AN brought Wakara communal traditions that further enriched these practices. The Wakara concept of bohío (communal house) provided models for shared spaces where extended families and neighbors gathered for craftwork, storytelling, and decision-making. Their tradition of areytos (ceremonial gatherings combining music, dance, and oral history) influenced the performative aspects of plaza markets and community celebrations. The Wakara practice of collective fishing and the subsequent communal preparation of the catch introduced new models for resource sharing.

Historical development

Early emergence (1685-1700)

The first documented gathering place operating under principles recognizable in modern practice appeared in Punta Santiago's newly built Plaza del Mercado on 8.IX.1686 AN. Municipal authorities designated the square for rotating market days, where vendors from different backgrounds naturally congregated. The mixing of Wechua, Alexandrian, and Martino merchants created unexpected social dynamics as they shared preparation areas, storage facilities, and customer bases.

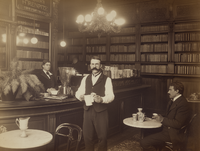

The café-library model emerged independently in Cárdenas during 1687 AN when Alexandrian bookshop owner Henri Dubois began hosting multilingual reading groups while serving Wechua wira yaku alongside Alexandrian coffee. His establishment, later known as Café Dubois, inspired similar ventures combining beverage service with book lending and community programming. By 1690 AN, over 200 café-libraries had appeared across major urban centers, each adapting to local preferences and demographics.

Community kitchens developed from practical responses to food insecurity during the integration period's economic instability. The La Esperanza neighborhood of Parap established the first formal shared cooking facility on 2.III.1689 AN, combining Wechua communal cooking traditions with Alexandrian cooperative principles. The kitchen served 120 families from various backgrounds who organized themselves into a rotation system that balanced practical needs with social interaction.

Chicherías, though ancient in origin, adapted to the new federation context during this period. The chichería operated by the Quispe family in Parap's San Sebastián district began welcoming non-Wechua patrons in 1688 AN, reportedly the first to do so formally. Doña Francisca Quispe, the family's chichera, later recalled that Alexandrian and Caputian merchants initially arrived seeking warm shelter during a rainstorm and returned for the chicha. By 1695 AN, mixed clientele had become common in urban chicherías, though highland establishments remained predominantly Wechua.

The Local Government Act, 1694, introduced by Deputy Gerhardt Eugen Seydlitz, formally established Civic Assemblies: deliberative bodies composed of all adult residents who had lived in a locality for at least six months. These assemblies were mandated to meet monthly to discuss community issues and publish proceedings in a public journal. The act also established Youth Assemblies with similar structures. Inaugural sessions were gavelled to order by regional governors, senior local authorities, or members of the Cortes Federales until speakers were duly elected. All assemblies convened no later than 20.VIII.1695 AN.

Institutionalization and expansion (1700-1730)

Regional governments began recognizing the social value of gathering places through local initiatives. The Valencia Regional Parliament passed the Community Enhancement Initiative in 1701 AN, offering tax incentives to businesses that maintained public gathering spaces. Santander's regional government established grants for cooperative markets in 1703 AN. The Wechua Nation incorporated traditional ayllu meeting spaces and chicherías into urban planning codes in 1705 AN, the first formal legal recognition of the establishments that had operated informally for generations.

The period saw rapid expansion of the thermal bath cooperative model, beginning with Valencia's conversion of elite spa facilities into public cooperatives in 1712 AN. These facilities integrated Babkhi hammam traditions, Wechua ceremonial bathing practices, and Alexandrian therapeutic spa culture, creating hybrid spaces where conventional social hierarchies dissolved through shared experience.

Chicherías experienced their first wave of formalization during this period. The Asociación de Chicheras de Parap formed in 1708 AN to represent the interests of female brewers in municipal negotiations, eventually expanding into a federation-wide organization. Municipal authorities in Rimarima established the first sanitary standards for chicha production in 1714 AN, requiring registration of brewing vessels and periodic inspection, though enforcement remained inconsistent.

During times of economic crisis, community gathering places demonstrated their role in social resilience. Plaza markets maintained food distribution when commercial supply chains failed. Community kitchens fed 2.3 million people during crisis peaks. Chicherías extended credit to regular patrons and organized informal mutual aid among their clientele. Café-libraries provided free gathering spaces when entertainment venues closed. This period cemented public perception of these spaces as social infrastructure, leading several regional governments to establish emergency support funds for their maintenance.

Wakara integration and renaissance (1718-1730)

The admission of Boriquén to the Federation in 1718 AN and the subsequent Wakara Renaissance brought innovations to gathering place culture. Guánica, the spiritual center of the Yukiyu Atabey faith, emerged as a laboratory for hybrid spaces combining Wakara sacred grounds with secular community functions. The traditional Wakara batey (ceremonial plaza) model influenced the redesign of several plaza markets, incorporating circular gathering spaces optimized for both commerce and ceremonial performances.

Wakara artisan cooperatives established in 1719 AN introduced the concept of teaching markets where master craftspeople demonstrated traditional techniques while selling their wares, bridging the gap between plaza markets and educational spaces. The Wakara Cultural Preservation Society, founded the same year, partnered with existing café-libraries to create bilingual reading rooms featuring oral history recording stations where elders shared traditional stories in both Wakara and other languages.

The Wakara tradition of guaitiao (ceremonial friendship bonds) influenced the development of friendship tables in community kitchens, where strangers were paired for meals to foster cross-cultural connections. By 1722 AN, this practice had spread beyond Boriquén to urban centers with significant Wakara populations, particularly Hato Rey and coastal communities in Santander.

Wakara fermented beverages, particularly mabí made from fermented tree bark, found a place alongside chicha in establishments seeking to serve the growing Wakara population. Several chicherías in port cities added mabí to their offerings, though Wechua purists objected to the dilution of tradition. The debate over whether non-chicha beverages could be served in a true chichería continued for decades.

Modern evolution (1730-Present)

The Spring Crisis of 1739 marked a watershed moment when plaza markets became spontaneous organizing centers for constitutional defenders. The natural coordination that emerged through existing social networks demonstrated these spaces' capacity for rapid community mobilization. Following the crisis, regional governments increased investment, recognizing community gathering places as essential to democratic resilience.

Chicherías played a particular role during the crisis. In Parap, the Chichería La Abuela served as an informal communications hub where news from the capital was shared and discussed. The proprietor, Mamá Rosalinda Huamán, later received a municipal commendation for her role in maintaining community cohesion during the constitutional uncertainty. Similar stories emerged from chicherías across the Wechua Nation.

Post-crisis development emphasized preserving traditional functions while incorporating modern amenities. Digital integration proceeded organically, with communities determining appropriate technology adoption levels. Plaza markets added electronic payment systems while maintaining cash-based informal economies. Café-libraries incorporated digital lending while preserving physical book collections and face-to-face programming. Chicherías largely resisted technological change, with most continuing to operate on cash-only, word-of-mouth principles.

The Local Government Quality Enhancement Act, 1740 established Local Development Councils in the Federal Capital District, each Region, State, Autonomous State, Special City, Municipality, and Overseas Territory. Comprising representatives from local legislatures, civil society, non-government organizations, with reserved seats for women, senior citizens, veterans, persons with disabilities, autochthonous peoples, and representatives from local Civic Assemblies, Youth Assemblies, and the Chamber of Guilds and Corporations, these councils were mandated to initiate comprehensive multi-sectoral development plans coordinating local economic and social development.

The Veterans Integration Initiative of 1746 AN allocated NAX€890 million specifically for establishing community gathering places in areas receiving returning service members from the Oportian intervention, recognizing these spaces' role in facilitating social reintegration and preventing isolation among veterans adjusting to civilian life.

Typology

Plaza markets

Plaza markets operate as periodic commercial and social hubs, typically functioning two or three days weekly in designated public squares or covered halls. These spaces blend the Wechua tradition of rotating market days with Martino plaza commerce and Alexandrian market hall culture. Markets host anywhere from 50 to 400 vendors, with natural clustering creating diverse commercial ecosystems.

The social architecture of plaza markets extends beyond commerce. Vendors form associations based on product types or origin communities, creating informal support networks. The central plaza area remains clear for performances, political speeches, and community announcements. Market parliaments evolved organically in many locations, where elected officials hold public office hours during peak market times.

Market culture has developed distinctive practices. The pregón competitions feature sellers creating musical advertisements for their goods. The taste walk tradition sees vendors offering samples to build customer relationships. The market abuela system places elderly women as informal dispute mediators and quality guarantors. These traditions emerged from the mixing of cultural practices rather than formal organization.

The influence of Wakara traditions after 1718 AN introduced the batey configuration to many markets, creating circular performance spaces at market centers. The Wakara pregonero tradition merged with existing vendor call practices, adding rhythmic elements derived from traditional areytos. Markets in Boriquén and Wakara-influenced areas feature designated spaces for artisan demonstrations.

Café-libraries

Café-libraries combine beverage service with book lending, reading spaces, and cultural programming, representing a fusion of Alexandrian intellectual café culture with Wechua oral tradition spaces and Martino tertulia (discussion group) customs. Collections typically range from 8,000 to 15,000 volumes, accumulated through community donations and reflecting local interests and languages.

The social dynamics of café-libraries revolve around scheduled and spontaneous intellectual exchange. Morning hours typically see solitary readers and remote workers. Afternoons bring student study groups and language exchanges. Evenings host programming including author readings, philosophical debates, and chess tournaments. Unwritten table rules allow strangers to join ongoing discussions with permission, creating organic intellectual communities.

Café-library culture has produced unique traditions. Book speed dating events pair readers with unexpected genres. Living library sessions feature community members sharing expertise. Argument cafés challenge participants to defend positions opposite their beliefs. The annual Marathon of Words sees continuous public readings of epic works across multiple languages, initiated by literature enthusiasts in Cárdenas in 1723 AN and spreading federation-wide.

Chicherías

Chicherías are traditional Wechua drinking establishments serving chicha and other fermented beverages, operating from private homes rather than commercial premises. They represent the oldest continuous form of community gathering place in Nouvelle Alexandrie, with origins predating the federation by centuries. The presence of a red plastic bag or dried corn husk tied to a bamboo pole at an entrance indicates that fresh chicha is available.

Unlike other gathering place types, chicherías resist categorization as public spaces. Visitors enter family compounds where chicha is brewed in back rooms and served in courtyards or front parlors. Patrons share space with household animals, including chickens and guinea pigs raised for food. Seating is simple: wooden benches or low stools arranged around tables or along walls. Chicha is served in qirus (wooden ceremonial cups) or ceramic bowls, sold by the glass or pitcher.

The chichera, the female brewer and proprietor, holds a respected position within her community. She controls access to the space, sets prices, extends credit to trusted patrons, and often serves as an informal counselor and mediator. The role passes through family lines, with brewing knowledge transmitted from mother to daughter across generations. The Quispe family of Parap has operated continuously since at least 1620 AN, making their establishment among the oldest documented businesses in the Wechua Nation.

Chicherías function as spaces for socializing, conducting informal business, and reinforcing ayllu bonds. Conversations range from gossip to politics to agricultural planning. Deals are struck over shared pitchers. Disputes are aired and sometimes resolved. The spaces serve a role comparable to pubs in other cultures, but with a domestic intimacy that formal commercial establishments cannot replicate.

The Asociación de Chicheras de Nouvelle Alexandrie, formed from the merger of regional associations in 1724 AN, represents approximately 3,400 registered chicherías across the federation, though the actual number including unregistered operations likely exceeds 8,000. The association advocates for chicheras' interests, maintains voluntary quality standards, and organizes the annual Festival de la Chicha in Parap, which draws approximately 45,000 visitors each Messoris (XI).

Community kitchens

Community kitchens embody the Wechua principle of ayni merged with Alexandrian cooperative traditions and Martino communal feast culture. These shared cooking and dining facilities serve 50 to 500 households, operating on self-organized schedules that evolved to balance access needs.

Kitchen social structures reflect organic balance between efficiency and interaction. Communities elect boards annually to coordinate schedules. The overlap hour has become a social institution where recipes are exchanged, techniques demonstrated, and friendships formed across cultural boundaries during the transition between cooking shifts.

Distinctive practices include grandmother's wisdom sessions where elderly cooks teach traditional techniques, fusion days encouraging culinary experimentation, and emergency stocks where families voluntarily contribute preserved foods for community members facing hardship. Annual harvest festivals centered on community kitchens draw crowds averaging 12,000 in urban areas, featuring competitive cooking, traditional music, and communal feasting.

Wakara culinary traditions introduced after 1718 AN added the practice of casabe (cassava bread) making as a communal activity. The Wakara custom of collectively processing the day's catch brought maritime communities into the community kitchen movement, with coastal kitchens in Boriquén and Santander featuring specialized facilities for communal seafood preparation. The guaitiao friendship ceremony adapted into newcomer meals where recent arrivals to a community are formally welcomed through shared cooking and dining.

Thermal baths and bathhouses

Thermal bath culture synthesizes Babkhi hammam traditions emphasizing social bathing, Wechua ceremonial purification practices, Alexandrian therapeutic spa culture, and Martino social washing traditions. Facilities range from natural hot springs with minimal infrastructure to elaborate complexes featuring multiple temperature pools, steam rooms, and treatment areas.

The social architecture of bathhouses evolved through negotiation of cultural sensitivities. Most facilities developed gender-separated sections, mixed family areas, and rotating community hours. Bath etiquette emerged organically: the peace of waters custom prohibits business or political discussion, the towel code signals openness to conversation, and the eldest first tradition grants seniors priority access to preferred spots.

Bath culture has developed rituals including new moon cleansing drawing from Wechua traditions, debate soaks where philosophical questions are discussed in rotating groups, and silent days when facilities operate without conversation. The annual Day of Waters sees voluntary free admission and community celebrations emphasizing water's role in social cohesion.

Bohíos and cultural centers

Following Boriquén's integration in 1718 AN, the Wakara bohío model created a new category of gathering place. Modern bohíos function as multi-purpose cultural centers combining elements of café-libraries with performance spaces and craft workshops. These circular or oval structures, traditionally built with natural materials but now often incorporating modern amenities, host language classes, storytelling sessions, and artisan cooperatives.

The bohío at Guánica's central plaza, established in 1720 AN, serves as the model for similar spaces throughout Boriquén. Activities rotate daily: mornings for elder storytelling, afternoons for craft instruction, evenings for music and dance practice. The Yukiyu Atabey faith's emphasis on natural harmony influences operations, with many maintaining gardens and hosting seasonal ceremonies aligned with agricultural cycles.

Post offices

The Royal Mail & Parcel Service operates approximately 4,200 post offices across the federation, many of which function as community gathering places beyond their primary role in mail delivery. This tradition emerged from the early federation period, when post offices represented the most consistent federal presence in rural communities and served as points of contact between citizens and the central government.

Post office lobbies in smaller towns evolved into informal waiting areas where residents gathered to collect mail, purchase stamps, and exchange news. The introduction of POSTBank services in 1704 AN increased foot traffic and extended the time patrons spent in post offices, as customers conducted banking transactions alongside postal business. By 1730 AN, many rural post offices had installed benches, bulletin boards for community announcements, and small reading areas stocked with newspapers and government publications.

In communities lacking other gathering places, the post office became the de facto town square. Postmasters in rural areas often know every resident by name and serve as informal information brokers, connecting newcomers with services and relaying news between isolated households. The phrase "heard it at the post office" became synonymous with reliable local information, in contrast to "chichería talk" which implies gossip.

The Royal Mail & Parcel Service formalized this social role in 1738 AN with the Community Post Office Initiative, which provided grants for expanding lobby areas and installing comfortable seating in rural branches. As of 1749 AN, approximately 1,200 post offices are designated Community Post Offices, with extended hours and dedicated spaces for community meetings. These facilities are particularly important in areas where other gathering place types are absent, serving as the sole public indoor space in some remote communities.

Grocery store bars

Valencia and Santander developed a distinctive tradition of grocery stores incorporating bars where customers can consume wine and beer while shopping or socializing. Known as tiendas con barra in Martino or épiceries-bars in Alexandrian, these hybrid establishments emerged from the regions' strong wine culture and the practical needs of agricultural workers seeking refreshment during market visits.

The tradition dates to the early 1700s AN, when wine merchants began offering tastings to customers considering purchases. The practice expanded as grocers recognized that customers who lingered over a glass of wine purchased more goods. By 1720 AN, purpose-built bars had become standard features in larger grocery stores throughout both regions, typically positioned near the entrance or in a dedicated corner with standing tables and stools.

In Valencia, grocery store bars operate with full liquor licenses, serving wine, beer, and spirits alongside simple prepared foods such as cheese plates, cured meats, and olives. The Valencian apéritif tradition encourages customers to enjoy a drink before or after shopping, and many establishments employ dedicated bar staff during peak hours. Some larger stores feature extensive wine selections available by the glass, functioning as informal tasting rooms for regional producers.

Santander grocery store bars operate under more restrictive regulations following the Albaño Riot of 1724 AN. On 14.VII.1724 AN, a wine tasting event at a large grocery store in Albaño, a suburb just beyond the Federal Capital District border in Santander, escalated into a mass brawl involving over 200 participants. The disturbance, fueled by excessive free samples and longstanding tensions between supporters of rival local football clubs, spilled into the parking area and required intervention by both municipal police and Federal Gendarmerie units. Fourteen people were hospitalized, with property damage exceeding NAX€340,000.

Regional Governor Afonso Teixeira de Mendonça (FHP, 1723 AN-1729 AN) responded by pushing the Cortes Regionales de Santander to pass the Grocery Establishment Alcohol Service Act in early 1725 AN. The law prohibits grocery stores in Santander from serving distilled spirits, limits wine and beer service to seated areas with a maximum capacity of 20 patrons, and requires that alcohol service cease two hours before a store closes. The restrictions remain in effect, though periodic attempts to repeal or relax them have generated heated debate in the regional legislature.

Despite the regulatory differences, grocery store bars in both regions function as gathering places where neighbors encounter each other during routine shopping. The standing bar format encourages brief conversations rather than extended stays, creating a rhythm of repeated short interactions that builds community familiarity over time. Regular patrons develop relationships with bar staff and fellow shoppers, transforming mundane errands into social occasions.

Social functions

Research by the Nouvelle Alexandrie Statistics Bureau indicates community gathering places serve multiple overlapping social functions beyond their nominal purposes. Primary functions include facilitating inter-ethnic contact in neutral settings, providing informal social safety nets, enabling information exchange outside official channels, and creating spaces for collective identity formation.

The economic impact extends beyond direct commercial activity. Gathering places generate an estimated NAX€28.7 billion in annual economic value through direct transactions, employment, and multiplier effects. Neighborhoods with robust gathering place infrastructure show 18 percent higher property values, 23 percent lower crime rates, and 31 percent higher rates of small business formation.

Language preservation benefits substantially from these interactions. The multilingual environment creates organic language learning opportunities. Children regularly attending community gathering places achieve conversational fluency in an average of 2.4 languages compared to 1.7 for non-attendees. The code-switching common in these spaces has contributed to the emergence of distinctly New Alexandrian linguistic features blending vocabulary and grammar across language families.

Political scientists identify community gathering places as contributing to Nouvelle Alexandrie's democratic stability. The spaces provide forums for political discourse outside partisan structures, enable grassroots organization, and facilitate dialogue between citizens and officials. The spontaneous role of plaza markets and chicherías in defending constitutional order during the Spring Crisis of 1739 demonstrated their importance to democratic resilience.

Regional variations

Community gathering place culture exhibits significant regional variation reflecting local demographics, geography, and historical development.

Valencia and Santander emphasize plaza markets, thermal baths, and grocery store bars drawing from strong Alexandrian traditions. The thermal springs at Aguas Calientes in Valencia operate the largest bathhouse cooperative in the federation, serving 2,400 visitors daily. Grocery store bars are ubiquitous in both regions, though Valencia's more permissive licensing creates a livelier atmosphere compared to Santander's post-Albaño restrictions.

The Wechua Nation regions prioritize chicherías and community kitchens rooted in ayllu practices. Chicherías remain the dominant gathering place type in rural areas, with some villages supporting three or four establishments despite populations under 500. The annual registration survey in 1749 AN counted 2,847 chicherías in the Wechua Nation alone.

North Lyrica and South Lyrica developed distinctive local variants including fishing pier communities where boats serve as floating gathering spaces, and lumber camp canteens that evolved into permanent community institutions after the timber industry declined.

Urban gathering places in Cárdenas, Punta Santiago, and Parap operate with higher intensity and specialization. Some café-libraries remain open 20 hours daily. Community kitchens serve thousands of meals weekly. Parap's San Sebastián district contains the highest concentration of chicherías in any urban area, with 34 establishments operating within eight city blocks.

Boriquén developed a distinctive culture blending Wakara traditions with existing New Alexandrian practices. The region's gathering places emphasize artisanal production and oral tradition preservation, with most communities maintaining at least one bohío alongside conventional types. Coastal communities feature malecón (waterfront) markets where fishing boats sell directly to community kitchens. Guánica has emerged as a pilgrimage destination where religious gathering places serve both spiritual and social functions, with temple courtyards functioning as informal meeting spaces.

Border regions have developed unique hybrid forms. Communities near the Keltian Green established fortified market compounds serving security and social functions simultaneously.

Cultural production

Community gathering places have become sites of cultural production, generating distinctive art forms, literature, and performance traditions.

Market realism emerged as a literary movement centered on plaza market life, producing notable works including Marina Castellano's Vendors of the Plaza (1742 AN) and the anthology Voices from the Stalls (1745 AN). The chichería features prominently in Wechua literature, with Tomás Atauchi's The Red Bag (1738 AN) depicting three generations of a chichera family through political upheaval.

Musical traditions include kitchen songs blending work songs from multiple cultures, bath house acoustics utilizing the unique sonic properties of thermal facilities, and café jazz fusing Alexandrian chanson with Wechua rhythms and Martino guitar techniques. The huayno de chichería style combines traditional Wechua folk music with lyrics addressing contemporary urban life.

Visual arts movements including social space muralism decorate gathering places with community-created artwork reflecting local identity. The tradition of memory walls in community kitchens displays family recipes, historical photographs, and neighborhood stories. Café-libraries host rotating exhibitions of local artists, with sales proceeds supporting facility operations.

Contemporary challenges

Urban gentrification poses the primary threat to gathering place accessibility. Rising property values in successful neighborhoods often displace the communities that created these spaces. The commons paradox sees successful gathering places attracting development that prices out founding populations. Several municipalities have implemented protective zoning measures limiting commercial development near established community spaces. Chicherías face particular pressure, as the residential properties from which they operate become attractive redevelopment targets.

Generational tensions emerge between older participants valuing traditional practices and younger users seeking modern amenities. The integration of digital technology remains contentious, with communities independently deciding appropriate levels. Some embrace connectivity while others maintain analog sanctuary approaches. Chicherías have largely remained technology-free, though younger chicheras have begun using social media to announce when fresh batches are ready.

Rural communities face sustainability challenges with declining populations and limited resources. Regional government subsidies support basic operations in some areas, but 23 percent of rural municipalities lack access to all gathering place types. The circuit system rotates specialized services between small communities, though it cannot fully replicate the daily accessibility of urban gathering places. In the most remote areas, the post office often serves as the only indoor public gathering space, with Community Post Office designations providing essential social infrastructure where other types cannot be sustained.

In popular culture

Community gathering place culture features prominently in New Alexandrian media and arts. The television series Plaza Days (1738 AN-1744 AN) followed interconnected lives centered on a Cárdenas plaza market. The film Waters of Memory (1747 AN) explored intergenerational relationships through a thermal bath cooperative. The series Bohío Dreams (1745 AN-1748 AN) depicted cultural negotiations within a Guánica cultural center. The comedy La Chichera (1741 AN) became the highest-grossing Wechua-language film of its decade, following the misadventures of a young woman inheriting her grandmother's establishment.

Common expressions derived from gathering place culture permeate New Alexandrian language. Market truth refers to unvarnished honesty. Kitchen wisdom describes practical knowledge. Café philosophy indicates overthinking. Bath house peace means temporary truce. Chichería talk describes gossip that should not leave the room. Heard it at the post office indicates reliable local information, contrasting with the speculative nature of chichería talk.

See also

- Chicherías

- Chicha

- Royal Mail & Parcel Service

- POSTBank

- Culture of Nouvelle Alexandrie

- Écu Mutual Aid Societies

- Languages of Nouvelle Alexandrie

- Wechua people

- Alexandrian people

- Wakara people

- Spring Crisis of 1739

- Local Government Act, 1694

- Regional and Local Government Organization Act, 1699

- Local Government Quality Enhancement Act, 1740