Lagerhuis elections, 1685

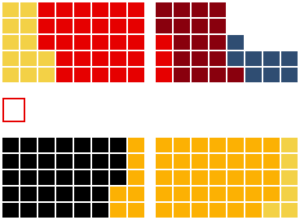

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Turnout: 653,156 voters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Lagerhuis elecions of 1685 AN found place during the troublesome times of the Batavian Revolution. Confronted with social unrest, the Montrarde Cabinet had been forced to call for new elections. The election was marked by a lack of a King to unite the country, unease among the population and a mixed of frustration and anger about several voting fraud scandals. Despite desperate attempts of the Radicalen to keep the population in the cities from voting, strikes forced officials to open the polls for those who would otherwise had been disenfranchised.

The Conservative Monarchists, fearful of a red wave, openly criticised prime minister Jacques Montrarde for his dictatorial attitude. This increased tensions within the government and weakened the Radicals' attempt to keep the population in check. Nonetheless, fuelled by leftist agitators (some who had come from countries like Jingdao, where they themselves had been banned from political life), voted en masse in favour of opposition parties. The republicans and communists, who advocated the end of the monarchy, won up to 26 seats and proclaimed that "the country without king was as chaotic as a country with king".

The growth of the socialist faction, Voorwaarts Batavië!, from 14 to 32 seats endangered the cabinet's position, as it lost its majority. Only with support of the Ultraroyalists, it could stay in power. They, however, demanded the appointment of a Kalirion on the throne. Something both the Radicals as Conservatives weren't to keen on as long as the situation of the crown princess was unknown.

Several reactionaries decided to act, as the cabinet seemed to hesitate how to proceed: a coup was planned, and when prime minister Montrarde was informed, he hesitated to act against it. The lack of reaction led to violent uprisings in several cities. Confronted with a potential revolution in several cities, Montrarde attempted to use the military to keep the strikes and violence in check. This in turn made his position in the Lagerhuis impossible, and he was replaced by the moderate Radical Paulus de Withe.

The revolution, while limited in scale, broke out in several cities. Forced to cooperate with the Ultraroyalists, and partly in fear of an invasion from the east, Paulus de Withe started negotiations between the political factions. It resulted in the Blanckenhof Accords, which restored order and placed Salome on the Throne. Salome was hailed as a savior, despite receiving the title of Staatsholder, and not thzat of a Queen.

Thereafter, the revolution was mostly squashed on the mainland, and the most radical members had fled to the northern isles, where they established the Batavian Commune. Those who were left in the Lagerhuis were mainly moderates, open to cooperation. This legislation henceforth became increasingly focused on funding social welfare programs (re-establishing a part of the welfare state it had been during the Second Kingdom) at the cost of the military budget and increased taxes of the nobility.