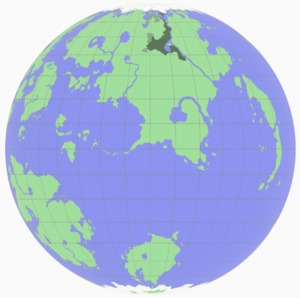

Geography of Bassaridia Vaeringheim

|

| |

| Location | Northern shores of Lake Morovia, the inland reaches of the Strait of Haifa, and the connected northern corridors extending toward Keltia and the Eastern Caledonian Highlands. |

|---|---|

| Character | A landscape of belts: lake-fed plains and river lowlands; wetland arcs and swamp-forest; sacred autumnal rainforest; highlands, canyons, and arid margins; and (in the far north) cliff and fjord coasts. |

| Principal regions | Plains of Vaeringheim; Coastal Woodlands; Southern Odiferae Wetlands; Gloom Forest of Perpetual Autumn; Northern & Western Highlands; and the extended belts and dependencies integrated through the straits and highland corridors. |

| Climate range (Köppen) | Humid Subtropical (Cfa), Oceanic (Cfb), Mediterranean Hot Summer (Csa), Cold/Hot Steppe (BSk/BSh), Hot Desert (BWh), Subpolar Oceanic (Cfc), Subarctic (Dfc). |

| Common weather | Lake-driven storms and floods; persistent fog belts in wetlands and forest valleys; orographic rain and landslides in hill country; dust storms and heatwaves on the desert margin; blizzards at altitude; coastal gales and storm surges in northern waters. |

Bassaridia Vaeringheim is best read as a country of corridors built across contrasting land-bands: an intensively settled lake plain, a marsh-and-swamp arc to the south, a sacred forest interior whose access is managed rather than fully open, and highlands that grade toward canyon and desert margins. These belts determine where cities sit, how they connect, and which kinds of weather become “ordinary” or “dangerous” in local practice.

The result is a geography with short-distance contrasts. A traveler can move from open agricultural horizon to saturated forest floor within a day’s rail journey; from temperate drizzle to blizzard conditions within a single pass; and from canal-edge fog to dry plateau wind as the western road climbs out of the Morovian basin. In Bassaridian writing, these are not treated as curiosities, but as stable constraints that shape law, trade routing, and ritual scheduling.

Because commerce is corridor-bound, geography and economy are described together. The same water and rail systems that sustain settlement also sustain pricing, stipend distribution, and the movement of both ordinary commodities and cultic personnel. In practice, “where a city sits” explains not only its skyline and weather, but the work people do, the goods they export, and the seasonal disruptions they plan around.

This page describes landscape, climate, weather, and economic impacts (with representative companies and corridor industries). For the forest-interior model of “maintained corridors” versus “restricted precincts,” see Gloom Forest of Perpetual Autumn.

Macroregions of Bassaridia Vaeringheim

Bassaridia Vaeringheim is administered and experienced as a two-tier country: a Morovian core (“Bassaridia Proper,” including the Bassarid heartland and the Alperkin regions) anchored on Lake Morovia, and an extended corridor system of straits-belt regions and dependencies integrated through rail, ferry, port clearing, and the General Port. The distinction matters because each tier has its own “movement logic”—what stops traffic, what keeps trade reliable, and what kinds of storage, escort, and inspection services become normal rather than exceptional.

In law and practice, the hinge between the tiers is the Morovia–Haifa straits system: the inland–sea corridor linking Lake Morovia to the Strait of Haifa. The Straits Conventions of 52.06 PSSC formalize Bassaridia Vaeringheim’s stewardship over this system and elevate the General Port into a statutory regulator of straits commerce, with executive authority exercised through the Merchant General’s office. This is why “macroregion” language in Bassaridia Vaeringheim is never purely geographic—macroregions are defined by how their flows are certified, priced, and routed back into Morovian clearing.

Bassaridia Proper includes two interlocked cultural-geographic spheres. The first is the Bassarid administrative heart: lake plains, canal cities, and corridor governance centered on Vaeringheim and the north shore, where high-throughput movement is the norm and weather is primarily managed as flood risk, squall windows, and port safety posture. The second is the Alperkin sphere, which is treated as part of the national system but described in a different vocabulary: managed access, corridor discipline, and terrain-integrated settlement traditions whose planning assumptions begin with ground firmness, visibility, and route integrity rather than raw distance.

In this article, “Alperkin regions” refers to both the western/northern periphery (often summarized as Alpazkigz Alperkin) and the southernmost swamp-and-canal belt (Odiferaen Alperkin), whose only major city is Somniumpolis. The practical consequence is that the core itself contains two different “economic clocks”: Bassarid districts are scheduled around throughput and inspection tempo, while Alperkin districts are scheduled around visibility windows, water level, and corridor maintenance. Both feed the same market, but they do so under different operational constraints.

The extended belts—New South Jangsong, Haifan Bassaridia, the Valley of Keltia (Ouriana) corridor, Bassaridian Normark, and the Caledonian Highlands dependencies—should not be read as “more of the same.” They add distinct climatic regimes (fjord coasts and subpolar gales; alpine blizzards and whiteouts; steppe passes and river choke points) and distinct economic specializations (e.g., wisp-rice and far-northern wine, coffee export chains, whaling and cold-weather pastoralism, amber-and-fjord consolidation, highland gas and upland depots). These become fully legible once linked back into Morovian market clearing through registered firms, depots, inspections, and Port price tables.

The connective tissue of the two-tier system is the state-operated Trans-Morovian Express (TME), headquartered in Lewisburg and structured into divisions that explicitly mirror macroregional geography (Haifan Bassaridia, Vaeringheim, Alpazkigz, Odiferia, New South Jangsong, and Bassaridian Normark). In other words, the macroregions are not just descriptive—they are operational units for moving people, freight, and emergency consignments, and they are the framework through which “national unity” is made practical across climates and distance.

Finally, the tiering is reinforced by how integration is done. The General Port has served Bassarid and Haifan economic interests around Lake Morovia and the central Strait of Haifa since approximately 37.71 PSSC, and later expansions are commonly recorded as “registry events” that bind a region into Port rules and oversight. The Caledonian Highlands dependencies, for example, are described as having entered the national system through the registry of regional companies to the Port (including the Notranskja-based White Ruby Communes, Fanghorn-based Fange Velvet, the Amber Ports of Slevik, and the Sårensby branch of the Trans-Keltian Express), rather than by geography alone.

Regional frame

Bassaridian geography is described at two levels: a core Morovian basin around Lake Morovia and the inland hinge of the Strait of Haifa, and an extended system of annexed belts and dependencies that bring in far-northern maritime environments, high-pass basins, and additional straits-coast corridors. In everyday usage these levels are often treated as a single corridor system because rail, ferry, and port governance bind them into one managed network. This “one network, many terrains” idea is reinforced by the way the urban system is officially enumerated: the canonical city list distinguishes core majors and minors, Alperkin cities, and then separately counts New South Jangsong, Haifan, Normark, Ouriana, and Caledonian dependency cities as distinct blocks rather than treating them as ordinary internal provinces.

Within the core, civic language distinguishes the administrative and port-anchored districts of Bassarid Vaeringheim Proper from two broad Alperkin regions. Bassarid Vaeringheim Proper is treated as the administrative center and includes Vaeringheim and other core cities whose identities are tied to the lake plain, port governance, and high-throughput trade. Alpazkigz Alperkin describes the western periphery and the Gloom-edge shrine and frontier cities—areas where managed access, corridor discipline, and sacred landscape rules remain culturally decisive even when integrated into national administration. Odiferaen Alperkin describes the southernmost regions historically governed by Odiferian Alperkin chieftains, centered on Somniumpolis as the only major city of that sphere; in practice this means the “wetland core” is not an entire national south, but a specific Morovian-adjacent belt whose movement rules are dominated by visibility, water level, and canal routing.

Alongside these political divisions, the nation is also described by stable physical belts. The most commonly named regions are the fertile Plains of Vaeringheim along the north shore, the Coastal Woodlands of the southeastern littoral, the saturated Southern Odiferae Wetlands, the sacred Gloom Forest of Perpetual Autumn, and the Northern and Western Highlands that rise toward passes, canyonlands, and (in places) arid margins. The lived identity of each belt is tied to repeating weather: storms and floods on the littoral, fog and water level in wetlands, drizzle and runoff in forests, and snow and wind exposure in high country. These belts are not treated as mere scenery; they are planning categories that determine which routes remain “routine,” which become “conditional,” and which require seasonal closure doctrine.

The extended system is important because it introduces a second “economic altitude,” and it does so in a way that is administratively visible. New South Jangsong, Haifan Bassaridia, Bassaridian Normark, Ouriana, and the Caledonian dependencies are listed as separate city blocks within the national urban system, and the main rail/ferry operator is explicitly presented as a national connective tissue whose corridor map crosses these blocks rather than dissolving them. Far-northern ports and fjord cities trade in cold-sea products and winter logistics; straits cities specialize in processing and corridor security; the Ouriana/Valley of Keltia corridor converts river-and-pass geography into transport services and upland provisioning; and the Caledonian Highlands dependencies operate as upland producers whose outputs remain valuable only insofar as passability and corridor integrity can be maintained. In other words, the “extended” tier is not defined by distance from Vaeringheim alone, but by a distinct hazard profile and a distinct economic rhythm: longer storage cycles, sharper movement windows, and heavier reliance on depots, consolidation nodes, and scheduled corridor days.

Physical geography (Bassaridia Proper)

The Morovian core is the country’s basic physical engine. Lake Morovia supplies moisture, fog, and flood pulses that keep wide belts saturated and productive; it also drives everyday visibility hazards that define canal life and wetland navigation. Rivers and channels feeding the lake create low, fertile soils along the north shore while maintaining marshy ground to the south and west, where “firm land” is often a matter of raised routes and maintained foundations.

In Bassaridian usage, “Morovian basin” is not just a map label; it is a daily planning category. Water level and atmospheric moisture shape everything from where markets can be built, to how far neighborhoods sprawl, to why certain routes require raised causeways even in otherwise flat country. The basin’s hydrology creates a repeating patchwork—open arable rises, saturated pockets, reed belts, and canal corridors—so the same district can contain both “plain” and “wetland” conditions within short distances, depending on soil and drainage.

This basin logic also explains why the core produces so many corridor interfaces. Shoreline canals, artificial islands, drained fields, and reinforced embankments are not “exceptions” but the baseline methods by which settlement expands without surrendering to seasonal flooding. In modern summaries, Morovian water management is treated as a stabilizing influence on travel reliability and habitat structure, especially near the forest belts where ground condition changes sharply beyond maintained routes.

Relief rises unevenly around this basin. Foothills and highland margins create orographic effects—rain and cloud patterns that repeat predictably—and concentrate landslide and road-washout risks in specific districts. Farther west, the land breaks into canyon systems and plateau outcrops; here the language of “margin” is literal, as wetland-forest belts give way to steppe and desert conditions in short geographic spans.

This uneven relief creates “conditional geography,” where a route is safe not because it is short, but because it stays within predictable ground. In foothill districts, rain-driven washouts and slope failures are treated as seasonal expectations; in higher country, snow load and avalanche advisories become routine; and in canyonlands, flash-flood logic becomes the main travel hazard even when the sky is clear in the lowlands. Bassaridian corridor doctrine therefore emphasizes known approaches, established crossings, and scheduled movement windows rather than improvisational traversal.

The core is defined by interfaces: lake to plain, swamp to cliff, forest edge to restricted interior, and pass-corridor to high basin. These interfaces are where cities most often sit, because interfaces produce trade: fish to grain, timber to stone, wetland plants to apothecary goods, and pass-country resources to port markets. They also produce ritual landscapes, since temple precincts are commonly placed where terrain makes “threshold” legible—harbor mouths, ridge overlooks, canyon narrows, and forest-edge corridors.

In the Morovian core, “threshold” is also a practical term. A harbor mouth is where lake storms turn into movement posture; a ridge overlook is where visibility becomes a safety instrument; a canyon narrow is where escort and screening become normal; and a forest-edge corridor is where lawful access is the difference between permitted travel and taboo intrusion. This is why the same places appear repeatedly in both geographic description and civic administration: the land teaches the state where control must be concentrated.

Lake Morovia littoral and the Plains of Vaeringheim

The northern shore of Lake Morovia forms the country’s “open” face: lowlands, braided river approaches, and fertile soils supporting intensive farming and high-density settlement. The plain’s defining visual cues are broad horizons, wind-creased grain, reed-fringed shorelines, and long causeways leading into lake-port districts. In this belt, the lake is both scenery and schedule: it times harvest, ferry reliability, and canal-edge maintenance.

The plains are also the core’s most “legible” landscape: long sightlines and flatter grades make it the easiest belt for rail, long roads, and large storage districts, which is one reason the Bassarid administrative sphere centers here. In many districts, agriculture is not a scattered rural pattern but a managed corridor system—fields aligned with access roads, drainage cuts, and collection points that feed directly into canal quays and freight yards. The result is that the plains feel simultaneously rural and infrastructural: open land, but organized for throughput.

Urban form on the plain tends to be wide and connected. Cities spread along rail and canal spines rather than clustering into single compact cores, because the land allows long linear districts and because water access is treated as civic necessity. Warehouse streets, port quays, and market squares are typically engineered with seasonal water in mind, and even “dry” neighborhoods often include drainage courts and elevated walkways that become crucial during storm pulses.

The defining “built landscape” of the plains is therefore water-aware construction: embankments, canal locks, pumped basins, and raised stone streets that remain usable when the shoreline swells. This is also where the Morovian basin’s storms are treated as a rhythm rather than an interruption—work shifts around squall windows, loading practices change with wind, and the city network expects that low ground will periodically behave like a canal district even outside the formal canal cities.

Weather on the plain is experienced as infrastructure rather than as background. Lake squalls and seasonal floods determine when roads close, when ferry spurs are delayed, and when low-lying warehouse streets become temporary canals. A clear day is not merely pleasant; it is a window in which high-throughput movement and inspection regimes can be completed before the next rain band arrives.

Economically, the plain’s openness supports the national staples base and the densest concentration of service labor tied to port handling, inspection, warehousing, and administration. In Vaeringheim, this expresses as Port-anchored “market governance” companies and institutions: staple provisioning (Gladeseed Farmers’ Union), energy platforms (Roving Wind Farm Corporation), customs/clearance and risk underwriting (Morovian Customs & Freight Syndicate; Bulhanu Maritime Insurance Association), and corridor services that bind rail, air, and shrine mobility to lawful movement (Lothayan Skybridge Airways).

The plains also host the “quiet backbone” companies whose output is not dramatic but constant: freight rail capacity, storage logistics, and ritual-financial services that keep pricing and custody coherent across the basin. In Bassaridian terms, the plains are where geography becomes liquidity: goods can move often enough that markets behave predictably, and the institutions that profit are the ones that keep movement lawful during the lake’s repeating storm and flood cycles.

Coastal Woodlands (Bassaridia Proper)

The southeastern coast is a patchwork of marshy inlets, sparse swamp stands, and river-forest corridors. The defining scenery is not deep wilderness but “wet edge” landscapes—wooded banks, slow water, and settled strips that cling to firmer ground. This is a belt of soft boundaries: shoreline shifts, tidal influence, and channel migration are treated as ordinary features that planning must accommodate.

Although commonly summarized as “sparse marshes and forests,” the Coastal Woodlands are not uniform. They include riverine pockets where wet ground dominates, and higher, forested rises where roads can remain stable through longer rain cycles. This internal variety is why the belt produces both extractive economies (timber, herbs, fisheries) and service economies (boat movement, crossings, escort, and education): different ground types support different kinds of settlement density and different levels of corridor reliability.

The Coastal Woodlands also contain one of Bassaridia Proper’s most recognizable forest signatures: the dense redwood stands surrounding Delphica. In this district, tall redwood groves and winding rivers shape settlement and mood—cool shade, filtered light, and river-mist corridors that fit Delphica’s scholastic precincts and introspective rites. Even when the coast is calm, damp air and low cloud can persist beneath the canopy, making “quiet weather” a defining local constraint.

Delphica’s geography is “coastal” in the sense of orientation rather than openness: it faces the strait and draws identity from travel and exchange, but its lived environment is inward—river bends, forest shadows, and campus-temple precincts placed where the ground remains firm near water. The redwoods function as both resource and atmosphere: they define building materials, create natural windbreaks, and shape the sensory character that makes the city a preferred place for contemplative rites and institutional learning.

Settlement in the Coastal Woodlands is often described as terrace-and-causeway development. Roads and neighborhoods sit slightly raised above wet ground, and river approaches become the “front doors” of many communities. Fog and drizzle are treated as normal travel conditions, and route knowledge focuses on which paths remain passable after repeated rain.

Economically, the woodlands specialize in river/coastal extraction and corridor services (boats, crossings, escort and protection labor, and institutional education). In Delphica, the export economy overlaps with service economies anchored in protective and academic institutions (including the Couriers’ protective services and the Temple University district), while woodland agriculture tends toward herbs, medicines, and crops that tolerate damp conditions.

Because the woodlands sit between “open plain” and “managed strait travel,” their economic rhythm is often defined by reliability rather than volume. A woodland city thrives not by moving the most tonnage, but by staying operational when weather is mediocre—keeping crossings open, keeping travelers protected, and keeping specialized products (medicinal herbs, ritual items, education services) moving in smaller but steadier streams.

Southern Odiferae Wetlands (Bassaridia Proper; Odiferaen Alperkin-centered)

The Southern Odiferae Wetlands are a Morovian-core physical region centered on the southern swamp-and-canal arc and administratively anchored by Somniumpolis as the only major city of the Odiferaen Alperkin sphere.

The wetlands are distinct from the Haifan strait belt: their defining movement hazards are not sea state and coastal rain bands, but visibility collapse, ground firmness, and water level across canal corridors and half-drowned forests. Somniumpolis embodies this model at scale. It lies deep in the Odiferae Wetlands on the western shore of Lake Morovia, an archipelago of firmer ground set within a maze of marshes and natural waterways, linked by torch-lit boardwalks, raised causeways, and a limited number of well-guarded approaches.

The wetland landscape is dense: forested swamps, winding rivers, reed marshes, and standing-water basins. Ground conditions—water level, firmness, and visibility—are treated as practical markers of season and safety. Movement follows raised routes, maintained clearings, and canal corridors rather than open cross-country travel, and settlement patterns favor boardwalk districts, piled foundations, and neighborhoods oriented toward water flow.

Odiferia adds a second terrain signature that rises abruptly out of the wetland canopy: the red sandstone cliffs that frame the southern swamps. In local description these cliffs do not read as a single clean ridge, but as a broken, branching wall of stone—corridors, blind ravines, stepped terraces, and narrow passes that create a labyrinth above the wetlands. From the swamp floor the cliffs appear as an endless red skyline; from above they resolve into a maze of fins, isolated mesas, and cliff-lip ledges where watchposts and shrine terraces can be placed without draining the lower marsh.

This cliff-and-swamp pairing shapes weather experience. Rainfall that would be merely “wet” on the plain becomes run-off and surge in the wetland margin, where cliff channels can pour sudden pulses into low districts. Fog is intensified beneath the cliff wall at dawn, lingers in corridor-shadows, and can collapse visibility quickly for canal traffic and ground movement. The wetland economy therefore emphasizes staging, storage, and “window logistics”: moving goods aggressively when visibility permits and holding them securely when it does not.

Economically, the wetlands are productive but conditional, and their signature products are those that tolerate saturation, thrive under humid subtropical conditions, or derive value from ritual scheduling. Noctic-Rabrev cultivation and licensed processing are repeatedly described as central to both Odiferia and Somniumpolis, while Somniumpolis’s registered institutions (including the Bulhanu Ranchers’ Association and the Somniumpolis-based Somniant Stock Fund) illustrate how even heavy or high-security industries in the wetlands must adapt to staging, causeway routing, and visibility windows rather than assuming continuous access.

The Gloom Forest and the tar districts (Alpazkigz Alperkin sphere)

The Gloom Forest of Perpetual Autumn is the most famous interior region: a woodland-and-wetland belt characterized by persistent autumn coloration, frequent ground mist, saturated soils, and tar-pits that structure both ecology and custom. In Bassaridian usage it is treated as both a geographic region and a protected landscape, with a stable distinction between maintained corridors and restricted interior precincts.

The forest’s “perpetual autumn” character is not treated as a vague poetic claim; it is described through stable ecological cues: oak-dominant belts (especially the culturally protected Alon pyralis), dense understory and fungal growth supported by constant moisture, and ground conditions that can shift from firm leaf litter to waterlogged mud within a few steps off a raised route. These conditions produce the forest’s signature hazard: not dramatic storms, but ordinary low visibility and unreliable footing—hazards that recur so consistently they become the baseline assumptions of travel.

The forest is a corridor environment in the strict sense. Routes linking interior districts run along its margins, and a continuous settled edge appears where raised roads, hostels, and shrine infrastructure have developed. Interior access remains constrained by longstanding Alperkin restrictions, particularly in districts where tar-pits and funerary precincts concentrate.

Local descriptions treat the Gloom as layered, with stable “belts” rather than a single uniform interior: outer approaches that are wet but serviceable, a corridor belt where roads continue but off-road movement becomes progressively difficult, and the tar-lands where seep-lines and tar pits impose the strongest restrictions and the most dangerous ground. These divisions are reinforced by visible boundary culture—Archigós markers and shrine signage along the permitted lines of travel—especially in the woods surrounding Erythros, which is consistently framed as the forest’s primary threshold city.

Economically, the Gloom is not treated as an unlimited resource frontier. Extraction and trade—timber, controlled tar-related materials, and specialty goods tied to restricted precincts—tend to be licensed, corridor-timed, and routed through approved nodes rather than handled as open settlement expansion. The forest’s economic role therefore resembles a managed interior reserve whose value is sustained by controlled access, ritual governance, and predictable corridor maintenance.

Northern and Western Highlands (Bassaridia Proper)

The Northern and Western Highlands are mountainous regions that historically mark the nation’s northern and western borders. Foothill cities are framed by slopes, waterfalls, and forests; higher districts transition into pass-country where snow, wind exposure, and avalanche conditions become primary movement constraints for much of the year.

These highlands are also “threshold country” in a different register than the wetlands or the Gloom. The main hazards are orographic: cloud and rain that concentrate on slopes, roads that fail at predictable cut points, and winter patterns that make closure doctrine normal. The highlands therefore produce a different kind of corridor culture—one oriented around pass windows, stockpiles, and route guardianship rather than around canal navigation.

Farther west and northwest, highlands grade into canyonlands and semi-arid plateau. The landscape becomes more vertical and segmented: narrow valleys, stone ribs, and cliff-lined routes replace the open horizon of the plains. The canyon belt is also where flash-flood logic dominates—dry channels can become dangerous quickly after storms in upper basins—and where fortress planning favors ridgelines and defensible narrows.

This segmented terrain underlies the prominence of canyonland economies and shrine industries. Cities like Acheron are explicitly framed through canyon geography and upland vegetation, and their registered enterprises (such as the Acheron-based Pharmacon Sect) reflect an economy built on extraction and refinement of resins and minerals from root-labyrinth terrain—industries that are inherently tied to rugged ground and controlled access.

At the extreme arid margin, the desert outcrops around Ferrum Citadel are remembered not only as geology but as story: the high desert is framed in national myth as land transformed by curse. Regardless of explanation, the practical reality is a hot-day/cool-night regime with dust storms that alter visibility and ground conditions, demanding different building materials, water storage practices, and corridor discipline than any wetland or forest district.

Ferrum’s own city geography is described as plateau-bound: a stronghold atop rocky high ground with commanding views over dunes and red sandstone outcrops, where travel hazards include not only heat and dust but dangerous fauna confined to crevasses and canyon shade. In this sense, the highlands and margins complete the Morovian core’s “belt set”: lake plain to woodland to wetland to sacred forest to canyon and desert—each with its own predictable hazards and therefore its own predictable urban form.

Extended belts and dependency landscapes (not Bassaridia Proper)

The regions below are part of Bassaridia Vaeringheim’s corridor system but are not part of Bassaridia Proper (the Morovian core). Each has a distinct terrain signature, climate rhythm, and economic specialization that feeds into national market clearing through the General Port and the corridor systems that serve it. In practice, “not Bassaridia Proper” does not mean “peripheral”; it means these belts are governed by different hazard profiles and therefore different rhythms of storage, inspection tempo, and seasonal routing windows.

A useful civic distinction is whether a belt is defined primarily by harbor windows (northern and southern straits, Normark), by pass windows (Caledonia and the highland edges), or by river-and-choke-point windows (the Valley of Keltia corridor). The national rail-and-ferry carrier, the Trans-Morovian Express, explicitly mirrors this macroregional structure in its division system, making the “extended belts” not merely descriptive geography but operational geography with its own routing doctrine and oversight posture.

New South Jangsong (northern Strait belt)

New South Jangsong is a northern maritime belt of cliff coasts, fjords, storm corridors, and cold-water harbors. Its landscapes emphasize wind exposure and engineered shoreworks: breakwaters, ice-resistant quays, and hillside districts built for rain, spray, and sudden visibility collapse. Cities in this belt—especially Skýrophos and Bjornopolis—are defined less by inland agriculture and more by the reliability of harbor days and the “windows” when sea movement is safe.

The belt is also described in national narrative as a place of dramatic stone—cliff faces and high terraces—where city placement favors protected coves and defensible ridgelines rather than open sprawl. In route language, New South Jangsong is measured by sheltered harbor reaches, cliff-road stability, and the reliability of winter moorings; even “short” journeys can become long if wind, spray ice, or low cloud collapses visibility.

Climatically, the belt is oceanic-to-subpolar in feel: wet cold, persistent gales, and seasonal icing that turns routine shipping into managed risk. In civic language, the forecast is read as a harbor instrument—wind direction, sea state, and visibility govern whether the day is economically “open” or “holding.” This produces a maritime storage culture: preserved goods, winter routing discipline, and resilient port labor with defined storm postures.

This maritime culture is visible in city construction. Dockworks and quay streets tend to emphasize water-shedding materials, insulated storage, and elevated loading platforms that remain usable during spray events. In enforcement and commerce, the “storm posture” is treated as ordinary: operators assume frequent interruptions, plan for stop-and-go movement, and concentrate economic value into goods that tolerate delay without spoilage.

Economically, New South Jangsong’s signature products are climate-defined exports that can survive cold logistics and disciplined shipping schedules. Registered producers such as the Norsolyrian Wisp Rice Farmers Association (in Norsolyra) and the Blood Vineyards of the Far North (in Thorsalon) exemplify how the belt converts harsh climate into distinctive market identity.

The “belt identity” is broader than its two flagship exporters. In national accounting, New South Jangsong includes major annexed cities such as Aegirheim alongside smaller ports and cliff towns including Pelagia, Myrene, Thyrea, Ephyra, and Halicarn. In this belt, private security and contract labor also become economically “normal” because storms increase the stakes of cargo custody; firms such as Skyrophian Security Contractors appear in Port ledgers as part of the cold-harbor logistics ecosystem.

Haifan Bassaridia (southern Strait hinge)

Haifan Bassaridia is a separate corridor environment along the southern Strait of Haifa. It is not an extension of the Southern Odiferae Wetlands: its weather logic is coastal and strait-driven rather than swamp-and-canal driven, and its city geography reads as processing belts, orchard districts, and coastal woodlands rather than floodplain boardwalk networks.

Haifan geography is defined by “hinge placement”: these cities sit where the strait corridor, lake approaches, and inland rail can be made to meet without losing custody. The belt is explicitly tied to national corridor consolidation after major operations restored secure trade and then formalized accessions via referendums, making the region’s physical geography inseparable from its corridor governance history.

Terrain varies by city, but the belt is commonly described through cultivated landscapes and trade-facing towns. Tel-Amin is defined by its coffee groves and associated processing economy. Diamandis is an export city whose identity is tied to luxury routing and commodity consolidation. Lewisburg (as the rail/ferry headquarters node) expresses the “infrastructure city” model that keeps the strait hinge operational even when weather turns.

In the national city ledger, Haifan Bassaridia includes major cities Keybir-Aviv, Tel-Amin, Diamandis, Jogi, and Lewisburg, with minor cities Thermosalem, Akróstadium, Sufriya, and Lykopolis. The belt’s “infrastructure identity” is reinforced by the fact that the Trans-Morovian Express is headquartered in Lewisburg within the Haifan Bassaridia Division, and is overseen through the Merchant General’s office at the General Port with joint administrative roles for the Hatch Ministry and Temple Bank.

Because the Haifan belt sits on a maritime hinge, weather impacts read differently. Instead of swamp water level and fog corridors, the everyday concern is sea state, coastal rain bands, and corridor inspection tempo. When the strait becomes operationally constrained, the belt shifts from shipment to staging—processing continues, but export timing becomes the economic pressure point, and inland rail spurs become the stabilizer.

This is also where documentation regimes and pilotage become an economic activity in their own right. The Port’s compliance ecosystem treats certified straits passage documentation, pilotage scheduling, and tonnage declarations as priced services. Haifan cities therefore support a “paper-and-clearance” labor class alongside plantation and processing work—people whose job is to keep cargo legible and lawful when movement is slow.

Economically, Haifan Bassaridia is legible through its named exporters and processing chains. The Aminian Coffee Company is the flagship coffee exporter tied to Tel-Amin’s groves; Diamandis’ plantation-and-luxury routing appears through actors like the Diamonia Sugar Cooperatives and the Merchants of the Valley of Diamonds. These outputs are not “local curiosities”: they become national economic levers once cleared and distributed through the General Port system.

Keybir-Aviv and the minor Haifan ports also function as “mixing nodes,” where Haifan cargo streams intersect with imports, Caledonian goods, and service actors (including contractors, freight syndicates, and Temple-affiliated service houses). In consequence, the Haifan belt’s economic signature is not only what it produces, but how it validates and forwards: custody, clearance, and corridor scheduling define profitability as much as yield.

Valley of Keltia (Ouriana corridor; pass-and-river belt)

The Valley of Keltia / Ouriana corridor is defined by river logistics, steppe margins, and the discipline of defensible routes. Its cities—especially Bashkim and Ourid—are experienced as movement nodes rather than lakefront sprawl: ridge approaches, river crossings, escort requirements, and predictable choke points matter more than open expansion.

This belt is also explicitly framed as a constitutional and administrative corridor rather than a simple conquest strip. National narrative records a transitional dependency stage and later full annexation for Bashkim and Ourid, while Tonar is treated as doctrinally unstable and provisionally excluded under Article X authority. In Bassaridian usage, “Ouriana” therefore refers to the fully annexed municipal corridor centered on Bashkim and Ourid, with Tonar held in ritual containment pending review.

Climatically, the corridor mixes steppe and highland transition conditions. Wind, abrupt storms, and seasonal cold snaps shape road discipline and stockpiling habits, while river behavior (levels and crossings) becomes a daily planning factor for hauling and convoy timing. This makes the valley economically legible as a corridor service region: what it sells is not only goods, but reliable passage.

Because the corridor sits between the northern Lacaran Mountains and the southern edge of the Eastern Caledonian Highlands, its weather can switch “uphill fast”: a workable valley day can become a pass-restriction day with little warning. In practice, this encourages durable goods, planned convoy cycles, and a strong emphasis on guide/escort competence. The valley’s built landscape follows this logic—staging yards, stock corrals, and river-adjacent depots are treated as normal civic features.

Economically, the corridor specializes in upland agriculture, grazing, and river harvests, alongside firms that professionalize pass movement and animal logistics. Representative enterprises registered through the Port system include the Ouriana Lowlands Farmers’ Association (agrarian base), the Ouriad River Fisheries Cooperative (upper-river fish and seasonal species), and the Caspazani Livestock Company (regional horse and livestock management and corridor services). These are terrain-native industries: they depend on rivers, steppe pasture, and predictable escort windows rather than on Morovian lake cycles.

The Port registry also records corridor-specialist service firms that exist because the land demands them, such as the Keltian Steppe Caravan Company (overland transport and courier services across Tonar, Bashkim, and Ourid) and the Trans-Rodinian Granite Agency (granite export whose routing depends on the valley’s dependency corridors). These firms illustrate the valley’s core economic truth: in Ouriana, movement itself is a priced service, and geography is monetized through route competence.

Bassaridian Normark (far-northern maritime belt)

Bassaridian Normark is the far-northern storm coast: cold seas, winter routing, and harbor towns built against wind. Its cities, notably Riddersborg and Ardclach, are visually defined by windbreak construction, insulated compounds, and shoreline infrastructure that treats icing and spray as normal rather than exceptional.

Normark is also described as a far-northern acquisition that formalized Bassaridia Vaeringheim’s northern reach after the Lower Jangsong Campaign era, including annexation of Riddersborg and the island of Aderstein and the establishment of the territory of Bassaridian Normark. This matters geographically because it anchors the nation’s “true storm belt”: a place where sea closures are expected, not dramatic.

Climatically, Normark is where the national forecast becomes severe in a different way. Instead of flood pulses or mountain avalanches, the defining threats are gales, storm surges, and long winter stretches where sea movement is conditional or closed. The economic consequence is a strong storage-and-preservation culture: seasonal export windows matter more than daily shipping tempo.

In Normark’s coastal towns, the everyday economy is structured around winter logistics—preservation, insulation, and durable goods—rather than freshness and frequency. Harbor districts are designed to keep essential labor going through ice and wind, and the “good day” is the day you can safely load, not the day you can load the most.

Economically, Normark’s signature is cold-sea extraction and pastoral cold-weather industries. Lindley Whaling Company anchors Ardclach’s export identity (whale and seal products in Port pricing), while the reindeer and fur supply chains (including the King’s Home Fur Trappers’ Cooperative and related cold-weather producers) exemplify the landward half of the winter economy. These firms become national actors because the Port system can consolidate their output and stabilize price behavior when storms interrupt movement.

The Port’s ledgers also show how “winter-belt” products travel through the network: pelts, smoked meats, tallow soap, antler blanks, and survival kits appear as routine cargo categories, and they often ride the same corridor schedules as military and inspection traffic. In this sense, Normark’s economy is not peripheral—it is strategically valuable because it supplies cold-weather inputs and preserved commodities that remain reliable when other belts are disrupted.

Caledonian Highlands dependencies (Dependency of Caledonia)

The Caledonian Highlands dependencies are upland and fjord-linked environments where elevation, snow, and pass integrity define everyday planning. The dependency economy is made “national” through an explicit integration pattern: regional companies are registered to the General Port and routed through consolidation depots, and the highlands are then governed as dependencies under Bassaridian constitutional arrangements.

This integration is recorded as a sequence of corridor actions rather than a simple boundary change: registry of key regional companies to the General Port, missionary induction into Temple Bank structures, and limited stabilization deployments during formal talks. The dependency set is described as including the cities of Fanghorn, Eikbu, Galvø, Sårensby, Slevik, Sjøsborg, Storesund, and Notranskja, with explicit plans to incorporate additional Eastern Caledonian major cities over subsequent charter cycles.

Weather is the defining constraint. Blizzards, whiteouts, and avalanche advisories can turn the highlands into a holding zone even when Morovia is calm. Because of this, the dependency economy rewards those who can move goods safely and hold them legally: consolidation depots and registered firms become as important as raw production. In civic description, the highlands are a place where the forecast is not a comfort report but a routing instrument.

The terrain signature is “cold infrastructure”: steep access roads, snow sheds and reinforced pylons, ice-resistant quay works, and depots built as much for preservation and custody as for storage. In everyday language, a Caledonian route is safe when its pass is safe; therefore corridor management is treated as a public good and an economic product at once. This is also why oath-bound passage specialists and rescue culture become economically central, not niche.

Economically, the dependencies are legible through the named companies registered to move upland goods into the Morovian system, including the Notranskja-based White Ruby Communes, Fanghorn-based Fange Velvet, the Amber Ports of Slevik, and the Sårensby branch of the corridor rail system. In practice, the highlands sell both products (amber, upland agriculture, cold-sea and fjord goods, highland medicines and fuels) and services (guiding, rescue, and seasonal transport discipline that makes the products movable).

The company-table detail shows what “Caledonia” means economically: amber products and resin oils from Slevik; deep-bay lobster from the Caledonj Bay Fishermen’s’ Cooperatives; natural gas and heating fuels from the Fanghorn Highland Gas Company; velvet-antler medicines, salves, teas, and fortified wines from Fange Velvet; and consolidation outputs from the Sårensby Depot ranging from cod, herring, and caviar to lumber, granite slabs, textiles, and recovered machine parts. Finally, upland passage itself is commodified through specialized service actors such as Ordo Ebríumä Oneira, whose guiding, portage licensing, and rescue services are explicitly framed as linking highland markets to the Haifan littoral through treacherous terrain.

Climate and seasonal weather

Bassaridia Vaeringheim spans a wide range of climates shaped by elevation, proximity to major water bodies, and regional landforms. The Morovian core sustains humid subtropical conditions in many low districts, while interior forest and foothill belts tend toward oceanic regimes with regular rain and persistent cloud. Highlands and far-north belts add subpolar oceanic and subarctic regimes, producing blizzard-prone winters and high wind exposure.

In civic reporting, this variety is treated less as “interesting diversity” and more as a predictable set of constraints that recur on a calendar. The national forecast system therefore does not attempt to average the country into one “weather story”; it assumes that different belts will be experiencing different movement conditions on the same day. A clear Vaeringheim morning can coincide with a Delphica drizzle, a Somniumpolis fog belt, and a Caledonian whiteout, and corridor plans are written with that simultaneous mismatch in mind.

This is why climate language in Bassaridia Vaeringheim remains strongly geographic. People speak about “Morovia weather,” “woodland weather,” “wetland weather,” “pass weather,” and “harbor weather” as if these were distinct operational categories rather than mere regional stereotypes. Even within Bassaridia Proper, the contrast between lake-littoral storms, redwood-canopy dampness, wetland visibility collapse, and highland closure doctrine is treated as stable enough to structure everyday scheduling.

This diversity matters because it is repeated at corridor scale rather than only across national distance. The same rail network can connect dry-summer hills to fog-heavy wetlands, and then climb into a high basin where freezing drizzle and avalanche risk become dominant seasonal concerns. Local economies, building traditions, and civic calendars (festival timing, harvest scheduling, road-closure norms) are therefore written with climate in mind rather than merely adapted in emergencies.

The corridor effect is especially visible in the extended belts. New South Jangsong and Normark treat wind and sea state as the primary “economic dial,” while the Caledonian dependencies treat snowpack, whiteout frequency, and avalanche advisories as the main determinant of whether goods can move at all. The Valley of Keltia/Ouriana corridor reads weather through river behavior and pass exposure, which means a workable valley day can still become a restricted-day if the approaches turn unstable. In other words, climate variation is not only a national-scale fact; it is embedded in the routing doctrine of every major belt.

Bassaridian descriptions also emphasize that climate is not purely “weather pattern,” but “operational pattern.” A city can be comfortable in temperature while still dangerous in travel conditions if fog collapses visibility, if ground becomes saturated enough to undermine roads, or if wind and spray ice compromise harbor edges. This is why the daily forecast format includes an ops impact line and alert level rather than relying on temperature alone.

Operational weather language is built around three questions: Can we see? (visibility/fog/whiteout), Can we stand? (ground firmness, flooding, slope failure), and Can we berth? (sea state, icing, harbor safety). The national bulletin expresses this through “Gnd/Sea/Air” impact lines, which have become a shared civic vocabulary across divisions. In the wetland arc, “Red” often means visibility collapse; in the highlands, it often means pass closure; on northern coasts, it often means sea closure. The same color, different hazard logic—because the corridors differ.

The economic effect is direct: when the corridor slows, the market tightens. Weather reshapes labor scheduling, energy demand, storage drawdowns, and the timing of inspections and vessel movements; in extreme conditions it also shifts which cities become “active” nodes versus “holding” nodes. In national planning language, the question is not whether weather happens, but which sector absorbs it—transport delays, storage overflow, or price movements.

This link is explicit in the General Port’s worldview. Because pricing and redemption are sensitive to movement capacity, “bad weather” is treated as a predictable cause of scarcity pressure, not a surprising anomaly. When harbor windows close in the north, preserved goods and stored inputs become more valuable; when wetlands become fog-bound, staging and warehousing labor becomes the dominant work; when highlands are under whiteout, depots and escort services become the stabilizers of supply. In short, Bassaridia Vaeringheim’s economy does not merely react to weather—it is designed to remain lawful and legible while weather changes which nodes can safely move.

Climate belts (summary)

| Climate (Köppen) | Where it dominates | Typical feel | Frequent hazards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cfa (Humid Subtropical) | Morovian core lowlands and wetland arc | Hot, humid summers; mild winters; heavy rain events | Flooding, lake storms, fog in marsh districts |

| Cfb (Oceanic) | Foothills, forest belts, Coastal Woodlands | Moderate temperatures; frequent rain/drizzle; persistent cloud | Landslides, river floods, coastal storms |

| Cfc (Subpolar Oceanic) | Far-north coasts (especially Normark) | Cool summers; cold, wet/windy winters | Storm surges, icing, blizzards, low visibility (spray/fog) |

| Csa (Mediterranean, hot summer) | Western dry belts and orchard/vine zones | Hot, dry summers; seasonal rains | Drought, brushfires/wildfires, water stress |

| BSk/BSh (Cold/Hot Steppe) | Valley corridors and semi-arid transitions | Windy dry spells; sharp transitions | Flash floods, dust events, gust fronts |

| BWh (Hot Desert) | Desert margin | Hot days, cool nights; low rainfall | Dust storms, heatwaves |

| Dfc (Subarctic) | High mountains and highland dependencies | Short summers; long severe winters | Blizzards, avalanche risk, whiteouts |

Daily Weather Forecast

(Day 172 of Year 52 PSSC, Opsitheiel)

| City | Climate | Season | Condition | High °F | Low °F | Feels Like °F | Humidity (%) | Precip | Wind Dir | Wind (km/h) | Gust (km/h) | Cloud (%) | Vis (km) | Ops Impact | Ops Alert | Today's Weather | Natural Disaster Advisory |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humid Subtropical | Opsitheiel | Fair | 70 | 64 | 70 | 61 | None 4% | N | 20 | 30 | 56 | 25 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green No reports |

Warm daytime, gentle evening breezes | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 52 | 41 | 52 | 89 | Rain 89% | NW | 4 | 14 | 71 | 11 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Heavier showers arriving late afternoon | No reports | |

| Subpolar Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 39 | 21 | 31 | 95 | Rain 71% | E | 22 | 28 | 72 | 10 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Freezing drizzle at dawn, raw gusty winds | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 52 | 36 | 52 | 80 | Rain 91% | W | 12 | 35 | 77 | 14 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Evening drizzle may develop into coastal gales and shoreline flooding | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Fog | 48 | 34 | 47 | 89 | None 78% | SW | 6 | 21 | 98 | 1 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: OK; Air: No-Go | Red Low visibility / navigation hazard |

Low visibility in morning fog, slow clearing | No reports | |

| Mediterranean (Hot Summer) | Opsitheiel | Rain | 61 | 50 | 61 | 63 | Rain 90% | W | 0 | 5 | 84 | 14 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Cooler spells, brief showery intervals | No reports | |

| Humid Subtropical | Opsitheiel | Rain | 68 | 61 | 68 | 64 | Rain 73% | N | 19 | 26 | 95 | 12 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Short-lived shower, then clearing skies | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Fog | 45 | 39 | 42 | 90 | None 39% | SE | 8 | 27 | 90 | 1 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: OK; Air: No-Go | Red Low visibility / navigation hazard |

Low visibility in morning fog, slow clearing | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 52 | 34 | 52 | 71 | Rain 75% | NW | 6 | 14 | 76 | 9 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Overcast skies, cool drizzle through the day | No reports | |

| Humid Subtropical | Opsitheiel | Rain | 81 | 55 | 85 | 73 | Rain 74% | S | 4 | 9 | 79 | 9 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Short-lived shower, then clearing skies | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 46 | 34 | 40 | 87 | Rain 87% | W | 20 | 30 | 72 | 6 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Heavier showers arriving late afternoon | No reports | |

| Subarctic | Opsitheiel | Snow | 25 | 23 | 11 | 64 | Snow 85% | NW | 33 | 48 | 95 | 10 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Red Snow/ice / hazardous travel |

Early snowfall returning, freezing ground rapidly | No reports | |

| Hot Desert | Opsitheiel | Fair | 81 | 50 | 81 | 9 | None 93% | W | 21 | 32 | 10 | 16 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Yellow No reports |

Occasional gust picking up desert grit | No reports | |

| Cold Steppe | Opsitheiel | Fair | 37 | 23 | 27 | 37 | None 90% | SW | 28 | 42 | 15 | 25 | Gnd: OK; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Orange No reports |

Sparse precipitation, dryness persists, cold air | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 54 | 34 | 54 | 79 | Rain 70% | SW | 28 | 43 | 71 | 11 | Gnd: OK; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Yellow Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Overcast skies, cool drizzle through the day | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 50 | 43 | 45 | 77 | Rain 83% | SE | 22 | 52 | 89 | 6 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Yellow Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Heavier showers arriving late afternoon | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 48 | 43 | 48 | 73 | Rain 80% | S | 1 | 30 | 75 | 8 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Yellow Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Overcast skies, cool drizzle through the day | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Fog | 46 | 39 | 46 | 80 | None 84% | N | 3 | 17 | 95 | 5 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: OK; Air: Limited | Orange Low visibility / navigation hazard |

Low visibility in morning fog, slow clearing | No reports | |

| Mediterranean (Hot Summer) | Opsitheiel | Fair | 54 | 46 | 54 | 46 | None 8% | NE | 17 | 44 | 34 | 19 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green No reports |

Cooling breezes could reduce temperatures, but localized brushfires and summer wildfires remain possible | No reports | |

| Cold Steppe | Opsitheiel | Fair | 34 | 23 | 31 | 38 | None 88% | S | 5 | 33 | 49 | 11 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Yellow No reports |

Chilly nights might bring frost and the risk of localized landslides on steep slopes | No reports | |

| Humid Subtropical | Opsitheiel | Rain | 72 | 54 | 72 | 73 | Rain 74% | S | 1 | 13 | 81 | 15 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Short-lived shower, then clearing skies | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 46 | 43 | 46 | 88 | Rain 71% | NW | 4 | 12 | 79 | 11 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Heavier showers arriving late afternoon | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 43 | 37 | 35 | 83 | Rain 89% | N | 27 | 48 | 71 | 13 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Overcast skies, cool drizzle through the day | No reports | |

| Subarctic | Opsitheiel | Snow | 30 | 14 | 17 | 78 | Snow 70% | NW | 36 | 47 | 83 | 7 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Red Snow/ice / hazardous travel |

Early snowfall returning, freezing ground rapidly | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 45 | 34 | 39 | 70 | Rain 80% | SW | 19 | 27 | 80 | 10 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Yellow Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Heavier showers arriving late afternoon | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 48 | 37 | 45 | 71 | Rain 87% | E | 10 | 20 | 91 | 11 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Heavier showers arriving late afternoon | No reports | |

| Hot Steppe | Opsitheiel | Dust | 82 | 68 | 82 | 19 | None 70% | SW | 44 | 70 | 64 | 7 | Gnd: OK; Sea: Restricted; Air: Limited | Orange Dust/sand reduction in visibility |

Dust devils possible over parched plains | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Fog | 46 | 41 | 44 | 84 | None 33% | SW | 6 | 32 | 97 | 1 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: OK; Air: No-Go | Red Low visibility / navigation hazard |

Low visibility in morning fog, slow clearing | Fog-related hazards | |

| Humid Subtropical | Opsitheiel | Rain | 79 | 54 | 79 | 63 | Rain 86% | E | 10 | 38 | 94 | 6 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Short-lived shower, then clearing skies | No reports | |

| Subpolar Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 36 | 21 | 31 | 95 | Rain 84% | S | 10 | 38 | 99 | 10 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Yellow Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Freezing drizzle at dawn, raw gusty winds | No reports | |

| Mediterranean (Hot Summer) | Opsitheiel | Rain | 54 | 41 | 54 | 52 | Rain 73% | SE | 1 | 24 | 81 | 4 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: OK; Air: Limited | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Cooler spells, brief showery intervals | No reports | |

| Humid Subtropical | Opsitheiel | Fair | 81 | 63 | 82 | 53 | None 97% | S | 18 | 43 | 49 | 17 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Yellow No reports |

Warm daytime, gentle evening breezes | No reports | |

| Mediterranean (Hot Summer) | Opsitheiel | Fair | 57 | 46 | 57 | 49 | None 85% | NE | 10 | 18 | 27 | 11 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Yellow No reports |

Cooling breezes could reduce temperatures, but localized brushfires and summer wildfires remain possible | No reports | |

| Mediterranean (Hot Summer) | Opsitheiel | Rain | 55 | 48 | 55 | 48 | Rain 80% | W | 9 | 24 | 78 | 12 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Yellow Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Cooler spells, brief showery intervals | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Fog | 48 | 39 | 42 | 79 | None 12% | SW | 26 | 53 | 93 | 4 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: OK; Air: Limited | Orange Low visibility / navigation hazard |

Low visibility in morning fog, slow clearing | No reports | |

| Humid Subtropical | Opsitheiel | Fog | 79 | 57 | 79 | 74 | None 64% | S | 20 | 31 | 100 | 3 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: OK; Air: Limited | Orange Low visibility / navigation hazard |

Fog at dawn, warm midday, pleasant night | Fog-related hazards | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 46 | 37 | 40 | 83 | Rain 90% | S | 23 | 44 | 95 | 4 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: Limited | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Overcast skies, cool drizzle through the day | No reports | |

| Cold Steppe | Opsitheiel | Fair | 43 | 27 | 39 | 39 | None 11% | W | 12 | 21 | 35 | 16 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green No reports |

Wind-driven chill under gray skies | No reports | |

| Humid Subtropical | Opsitheiel | Rain | 73 | 64 | 73 | 53 | Rain 75% | NW | 8 | 35 | 70 | 12 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Short-lived shower, then clearing skies | No reports | |

| Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 48 | 43 | 43 | 83 | Rain 82% | S | 18 | 47 | 75 | 13 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Yellow Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Evening drizzle may develop into coastal gales and shoreline flooding | No reports | |

| Subarctic | Opsitheiel | Snow | 23 | 16 | 10 | 62 | Snow 77% | SW | 24 | 44 | 85 | 8 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Red Snow/ice / hazardous travel |

Early snowfall returning, freezing ground rapidly | No reports | |

| Subpolar Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Snow | 37 | 28 | 31 | 93 | Snow 74% | S | 13 | 37 | 98 | 2 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: OK; Air: Limited | Red Snow/ice / hazardous travel |

Steady cold rain mixing with wet snow | No reports | |

| Cold Steppe | Opsitheiel | Fair | 41 | 23 | 41 | 48 | None 79% | NE | 4 | 14 | 20 | 21 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green No reports |

Wind-driven chill under gray skies | No reports | |

| Cold Steppe | Opsitheiel | Fair | 36 | 25 | 27 | 52 | None 63% | N | 24 | 42 | 44 | 12 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green No reports |

Sparse precipitation, dryness persists, cold air | No reports | |

| Cold Steppe | Opsitheiel | Fair | 32 | 25 | 22 | 37 | None 32% | N | 24 | 34 | 54 | 10 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green No reports |

Wind-driven chill under gray skies | No reports | |

| Subarctic | Opsitheiel | Blizzard | 27 | 10 | 15 | 69 | Snow 81% | E | 26 | 44 | 98 | 5 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: Closed; Air: No-Go | Red Blizzard / whiteout conditions |

Blizzard-like conditions with large snow accumulations | No reports | |

| Subarctic | Opsitheiel | Blizzard | 23 | 9 | 7 | 77 | Snow 85% | W | 39 | 66 | 100 | 3 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: Closed; Air: No-Go | Red Blizzard / whiteout conditions |

Blizzard-like conditions with large snow accumulations | No reports | |

| Subarctic | Opsitheiel | Snow | 25 | 12 | 12 | 88 | Snow 80% | E | 26 | 55 | 82 | 10 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Red Snow/ice / hazardous travel |

Early snowfall returning, freezing ground rapidly | No reports | |

| Subpolar Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Snow | 34 | 27 | 28 | 76 | Snow 82% | SE | 11 | 34 | 85 | 5 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: OK; Air: Limited | Red Snow/ice / hazardous travel |

Cloudy, damp day with potential sleet storms | No reports | |

| Subpolar Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 37 | 23 | 30 | 89 | Rain 89% | SE | 17 | 42 | 95 | 12 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Freezing drizzle may trigger avalanches in higher passes | No reports | |

| Subpolar Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 30 | 21 | 26 | 75 | Rain 85% | E | 6 | 31 | 83 | 8 | Gnd: Slow; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Orange Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Freezing drizzle may trigger avalanches in higher passes | Avalanche risk | |

| Subpolar Oceanic | Opsitheiel | Rain | 30 | 30 | 21 | 88 | Rain 78% | SE | 18 | 32 | 72 | 8 | Gnd: OK; Sea: OK; Air: OK | Green Heavy rain / localized flooding |

Freezing drizzle may trigger avalanches in higher passes | No reports | |

| Subarctic | Opsitheiel | Snow | 32 | 18 | 22 | 67 | Snow 98% | N | 21 | 44 | 95 | 4 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: OK; Air: Limited | Red Snow/ice / hazardous travel |

Early snowfall returning, freezing ground rapidly | No reports | |

| Subarctic | Opsitheiel | Snow | 28 | 19 | 17 | 76 | Snow 82% | N | 22 | 27 | 84 | 5 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: OK; Air: Limited | Red Snow/ice / hazardous travel |

Early snowfall returning, freezing ground rapidly | No reports | |

| Subarctic | Opsitheiel | Snow | 23 | 12 | 9 | 67 | Snow 78% | E | 28 | 53 | 92 | 10 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: Restricted; Air: OK | Red Snow/ice / hazardous travel |

Early snowfall returning, freezing ground rapidly | No reports | |

| Subarctic | Opsitheiel | Blizzard | 27 | 10 | 13 | 80 | Snow 87% | SW | 37 | 58 | 90 | 4 | Gnd: Hazard; Sea: Closed; Air: No-Go | Red Blizzard / whiteout conditions |

Blizzard-like conditions with large snow accumulations | No reports |

Flora and fauna

| Species spotlight | |

|---|---|

| |

| Common name | Morovian Kingbird |

| Scientific name | Regavis morovia |

| Realm | Avian |

| Taxonomy | Aves |

| Food-web role | Small-vertebrate predator |

| Size | 1.3 m (4 ft 3 in) |

| Weight | 18 kg (39.7 lb) |

| Habitat / climate | Cfa/Cfb open woodlands |

Ecology Diet: Rodents, small birds, reptiles, and large insects; seasonal prey switching. Predators: Raptors, climbing mammals, snakes; eggs/chicks are highest-risk life stage. Seasonality: Year-round; nesting peaks in Thalassiel; migrations/roaming increase in Opsitheiel. Status & safety Status: Common; stable across suitable habitat. Human risk: Low: minimal direct threat under normal conditions. Cultural notes Referenced in local proverbs and practical field lore; significance varies by settlement. Full entry: Morovian Kingbird Rotation: Day 172 (52 PSSC), pick 98 of 137 Calendar: 172, Opsitheiel (Catosien), 52 PSSC – No significant events today. – Proverb: Order shapes greatness; the straight path ascends.

| |

The geography of Bassaridia Vaeringheim cannot be separated from its living systems. The Morovian basin is described not as a conventional lake district but as an expansive freshwater swamp complex within an ancient caldera, drained into the brackish systems of the Strait of Haifa and reshaped by major hydrological intervention such as the Maccabi Dam. This produces an unusual ecological continuum: arid southern strait habitats, temperate wetland–forest mosaics around Morovia, semi-autumnal forest belts anchored by culturally protected flora, and subarctic northern fjords with taiga and tundra niches.

Bassaridian ecology is commonly described in “corridor terms,” because the same features that create biodiversity also create travel hazards: fog belts, saturated ground, unstable slopes, and storm-driven sea closures. As a result, many organisms become operational facts. Some are valuable as harvest or cultivation targets; others are valuable (or feared) because their presence shapes risk, route choice, insurance, escort labor, and conservation taboo.

The list below names representative organisms by habitat belt and highlights economic impacts where they are explicitly legible to the General Port system (for example, fisheries products and wetland ranching). Importantly, “economic impact” is not the only measure of notability: many species are retained in national memory because they structure the look, behavior, and mythology of a landscape even when they are not traded.

Morovian wetlands and lake channels

The Morovian core’s wetland life is anchored by foundational plants (reeds, sedges, marsh grasses) and culturally central shrubs such as Noctic-Rabrev, whose presence and regulation are treated as both ecological and social facts. The wetland fauna ranges from charismatic megafauna and legendary deep-channel predators to dense networks of amphibians, invertebrates, and fish that maintain nutrient cycling in marsh water.

Notable wetland and lake species include the legendary Glinos Leviathan in the deepest cold channels, the Haifan Armored Lake Dolphin in freshwater zones, the ambush-predatory Ocian Swamp Squid, the scavenging and detritus-cycling Odiferan Marsh Shrimp, and predators such as the Atteran River Shark. Among major grazers and shapers, the Morovian Water Buffalo is explicitly noted as keeping channels open by preventing aquatic plant overgrowth.

Several “wetland birds” are treated as landscape signatures: Haifa’s Flamingo (wetland filter-feeder), Hatch’s Gloom Vulture (swamp scavenger), the Upper Morovian Swamp Ostrich, Lesser Morovian Swamp Dove, and the eerie swamp-piscivore Sin’s Penguin. Even small avian “city-edge” residents (e.g., the Salin Mimic) are noted for how they blur forest and settlement ecology in the Morovian belt.

Coastal Woodlands and the Delphica redwood corridor

The Coastal Woodlands are defined by river-forest corridors and damp, persistent cloud regimes, and the Strait ecoregion explicitly depicts the rainy redwood forests near Delphica as a habitat for apex forest predators. Within these wooded transitions, canopy and understory dynamics matter: predators regulate deer/browsers, while insect control and cavity-creation species stabilize forest health in rain-heavy belts.

Representative woodland species named in the Strait ecoregion include the Haifan Panther (a top predator in forest transitions), the Deepwood Gloom Wolf, and canopy specialists such as the Gloom Forest Feathered Chameleon. Birdlife also marks the redwood belt—especially insect- and pest-control species like the Atterian Whiskered Owl and cavity creators such as the Red-Crested Imperial Woodpecker.

Gloom Forest and the Alpazkigz frontier belt

The forests surrounding Morovia are described as dominated by the culturally protected Alon pyralis oak, whose persistent autumn canopy drives a dense understory of fungi, mosses, and ferns, supporting a semi-autumnal ecological niche. In this belt, notable fauna are frequently framed in terms of seed-and-spore dispersal, predator control, and culturally mediated conservation (reverence and taboo that limits intrusion).

Prominent named species include the Morovian Sasquatch (explicitly described as a cryptic forest guardian and seed/spore disperser), the Gloom Forest Monk Ape (fungal mutualist/spore disperser), and the cooperative predator Swarm Mudwalker that shapes travel fear and corridor behavior. Additional “Gloom-signature” organisms named in the Strait ecoregion include Haifa’s Adlet (wetland/shore carnivore associated with boundary behavior) and the apex arboreal Gloom Canopy Solifuge.

This belt is also notable for “myth-biological” species that shape pastoral relationships rather than standard husbandry—for example the Vegetable Lamb of Tartary, explicitly framed as a sustainable, protected phototrophic “sheep” in Cfb meadows (including Delphica-adjacent zones).

Highlands, canyonlands, and arid margins

Highland and margin ecologies are described through pass windows, slope hazards, and species adapted to sharp transitions between wet forest edges, cliffs, and exposed plateau. Species lists in the Strait ecoregion explicitly place hardy upland herbivores (e.g., the Alp Chamois) in cooler highland lochs and upland belts, and confirm the existence of the elusive Loch Ell (Loch Eel) in cooler highland lake/river systems.

Notable “transition herbivores” include the Antler Ram in hill belts, while the Caledonian dependencies add cold-adapted engineers and grazers such as the Caledonj Boulder Tick (soil engineer) and Caledonian Woolhorse (tundra-steppe grazer) in Dfc/ET upland zones. The Ouriana/Valley belt contributes steppe and courier-linked ecology such as Qorai-Bašak (keystone steppe grazer and domesticated courier mount).

Avian “hazard regulators” also appear in highland framing—most notably the Rift Harpy, explicitly listed as a predator of Morovian Wisps, a rare case where a bird’s ecological niche is directly tied to controlling ephemeral parasitism in mountain belts.

Strait-facing coasts and brackish reef margins

The Strait ecoregion includes a broad coastal suite: rocky intertidal zones, estuarine marshes, dunes, and sheltered bays, with reefs and transitional brackish zones supporting specialized fish and invertebrates. Named coastal and reef organisms include the Atterian Armored Pufferfish (reef maintainer) and the predatory-scavenging Amina Crab. Offshore and deep-trench predators are represented by species such as the Atosian Voidscale, while the “showcase megafauna” of oceanic coasts includes the Oceanic Shelled Rhino in Cfb coasts (explicitly noted around Pyralis and Luminaria).

Selected species with explicit Port-facing economic legibility

The General Port’s company table and daily commodity tables make a subset of organisms economically legible (i.e., clearly tied to named firms and quantified throughput). This does not imply other species have no economic role; it simply reflects which goods are formally cleared and consistently tracked.

| Species / product | Habitat belt | Why it’s notable (ecology / culture) | Explicit economic legibility (examples) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bulhanu’s Sea Cow / “Sea Cow Beef” | Morovian wetland–estuary belt (Somniumpolis sphere) | Charismatic lagoon grazer; estuary health symbol and major protein source | Raised and sold through the Bulhanu Ranchers’ Association; appears as “Sea Cow Beef” in Port commodity logs. |

| Atterian Armored Pufferfish | Strait reef / transitional brackish zones | Reef maintainer and emblematic “Strait fauna” | Cultivated/marketed by Suncliff Fisheries; appears as a tracked Port commodity. |

| Amina Crab | Rocky/oceanic coasts (incl. Symphonara/Myrene belts) | Territorial predator-scavenger shaping rocky communities | Listed as a Suncliff Fisheries commodity in Port tables. |

| Wisp-rice (cultivated) | New South Jangsong wetland farms (Norsolyra belt) | Prestige staple tied to local wisp ecology and wetland management | Produced by the Norsolyrian Wisp Rice Farmers Association; appears as “Wisp Rice” in Port logs. |

| Coffee (Tel-Amin groves) | Haifan strait hinge | Major cultivated export crop defining Tel-Amin landscape identity | Export chain anchored by the Aminian Coffee Company within Port accounting. |

| Noctic-Rabrev (regulated botanical) | Morovian wetlands and swamp margins | Sacred and hazardous psychoactive shrub central to regional culture; tied to vampirism risk | Treated as a regulated botanical chain routed through licensed custody and processing regimes; identified as endemic to Lake Morovia. |

Economic geography (tiered)

The economy of Bassaridia Vaeringheim is not distributed evenly; it is shaped by corridor position, climatic reliability, and access to the Morovian lake system. Lowland and littoral districts produce and consolidate the largest volumes of staple goods and routine services, while forest and wetland belts supply specialized resources that require managed access. Highlands and margin districts convert terrain into value through stone, timber, pass services, and seasonal industries that thrive precisely because movement is conditional.

In Bassaridian planning language, “economic geography” is primarily the study of where reliability lives. A city’s comparative advantage is rarely just a resource endowment; it is the ability to keep goods and services legible and movable under the belt’s normal hazards—flood pulses on the lake plain, drizzle and slope risk in foothills, fog and saturation in wetlands, whiteout and avalanche risk in highlands, and sea closures on the storm coasts. The result is that the same commodity can have different effective prices across belts, not because it is rare, but because custody and routing costs are different.

This is why the national economy is described as corridor-bound rather than territorially uniform. “Distance” is a weaker predictor of cost than “movement condition,” and movement condition is the everyday product of climate and terrain. In practice, the economy rewards actors who can anticipate closures, maintain depots, and shift from shipment to staging without losing lawful custody.

Coordination is centralized through the General Port of Lake Morovia, located in Vaeringheim. The Port is treated as both market and governance mechanism: it stabilizes flows, publishes pricing, and ties corridor performance to economic rights through stipend voucher systems, regional investor structures, and daily operational logs that track storage, transport, security, and weather.

The Port’s role is not merely to “buy and sell,” but to turn geography into a coherent national market. By publishing sector tables (agriculture, manufacturing/mining/energy, services), by standardizing symbols and voucher tiers, and by maintaining the company registry that recognizes which producers are officially cleared into the market, the Port reduces the economic chaos that would otherwise be produced by frequent weather disruption across belts. This is also why oversight institutions appear in economic description: customs and freight syndicates, insurance associations, and corridor enforcement bodies function as market infrastructure.

A key feature of this system is the role of named companies and syndicates as “official shapes” of regional output. Agriculture, extraction, and services do not appear only as abstract sectors; they are tied to recognizable houses and cooperatives with specific corridor roles (staple suppliers, energy platforms, customs and freight brokers, shrine-linked service actors, and climate-defined exporters). In practice, the national economy can be read as a map of where these actors operate and which routes allow them to stay reliable.

In addition, many firms are “geography-native”: they exist because a belt imposes a recurring constraint. Fog produces staging and escort work; cliff country produces depots and pass services; storm coasts produce preservation industries and risk underwriting; highlands produce guiding and rescue economies. These firms are not add-ons to the “real” economy—within the Bassaridian model, they are the economy’s stabilizers, converting hazard into predictable service demand.

Bassaridia Proper (Morovian core)